Related pages

Sanath and Buddhika Lamabadusuriya - celebrating South Asian Heritage Month

Celebrating South Asian Heritage Month- Sanath and Buddhika Lamabadusuriya

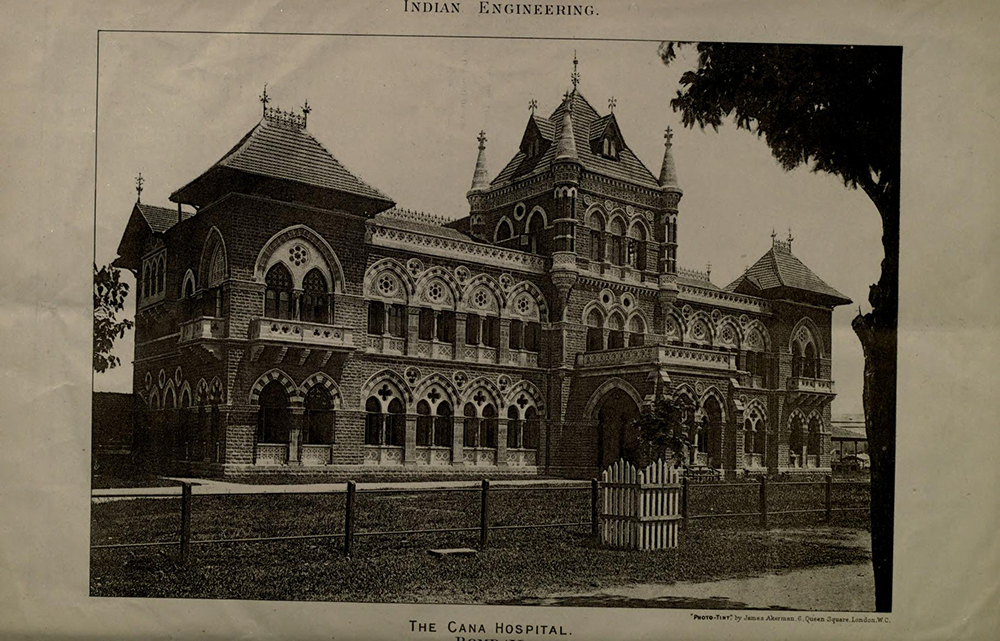

Dr Dossibai Patell

Dr Dossibai Patell (1881–1960) was the first woman licentiate of the RCP, admitted in April 1910.

Vattoru-pota: a Sri Lankan doctor’s manual

Explore how this fascinating Sri Lankan manuscript was created and why it might have been of interest to early 19th century European doctors.

Pamela Forde

Introduction of Western Medicine into Northern Sri Lanka: From Massachusetts to Manipay

Guest blogger Professor Nadarajah Sreeharan explores the introduction of Western medicine into Northern Sri Lanka in the 19th century.

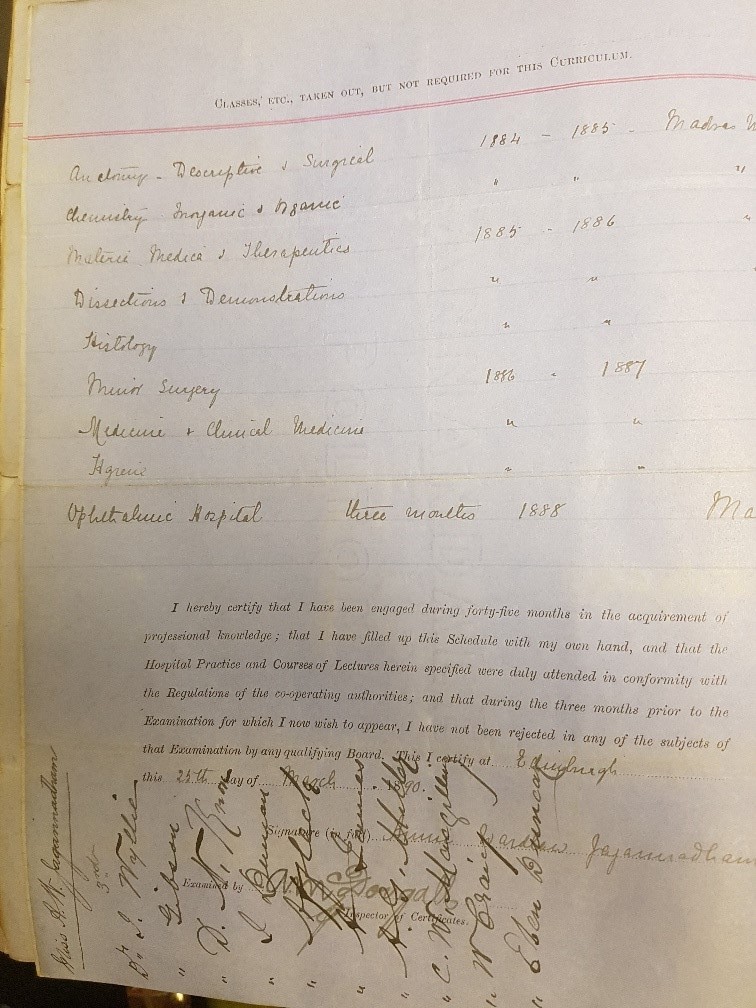

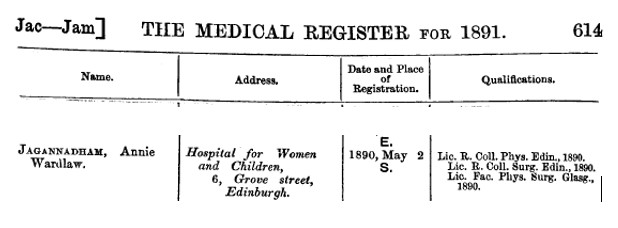

The Bern theses: pioneering medical women

In 1877, three British women – Sophia Jex-Blake, Edith Pechey-Phipson and Annie Clark – travelled to Bern in Switzerland to study medicine. The medical pioneers’ MD theses are part of the RCP library.

Alana Farrell