Throughout the 19th century European medical practitioners working in South Asia had very little experience of tropical climates and diseases. They often relied on local medical practitioners for the treatment of local diseases yet still considered western medical techniques and knowledge superior.

This reliance on local medical practices led many European doctors to develop an interest in the development of medical traditions and the objects and documents associated with them. This manuscript in our collection is a Sri Lankan doctor’s manual written in Sinhala. Unfortunately, there are no surviving records showing exactly how the Royal College of Physicians came to have this early 19th century palm leaf manuscript.

European physicians in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (known as Ceylon until 1972) is a former British colony. Over the first few years of the 19th century the British East India Company occupied increasing amounts of the island, taking over from Dutch colonisers, until it became a British colony in 1815.

After an early trade in coffee production failed in the middle of the 19th century, its main export became tea, until the widespread introduction of rubber plantations in the early 20th century. Ceylon achieved independence in the early 20th century, becoming a republic in 1948.

This ethnically diverse island is home to a majority Sinhalese population, with the next largest group being Tamil. The two official languages are Sinhala (the language of this doctor’s manual) and Tamil and the main religion is Buddhism.

British physicians that went to south Asian British colonies like Sri Lanka had very little knowledge of the local diseases or demands of the tropical climate and would look to local practitioners for advice. The local knowledge and medical practices were still seen, however, as inferior to Western medicine. There was a widespread assumption that racial differences had an impact on the efficacy of certain treatments. For example, a vaccine developed from the tissue of a healthy white person was considered to be more effective than that acquired from a healthy member of an indigenous group.

The interest in local practices is likely behind the presence of this Sri Lankan doctor’s manual within our collection. European doctors would either purchase or appropriate works on local medical treatments and systems, returning with them to Europe. There are no exact details in our records of how this manuscript was acquired and the first mention of it is in a catalogue of Asian manuscripts and printed works compiled by a former professor of Arabic studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, Professor A.S. Tritton, in 1951.

Creating a palm leaf manuscript

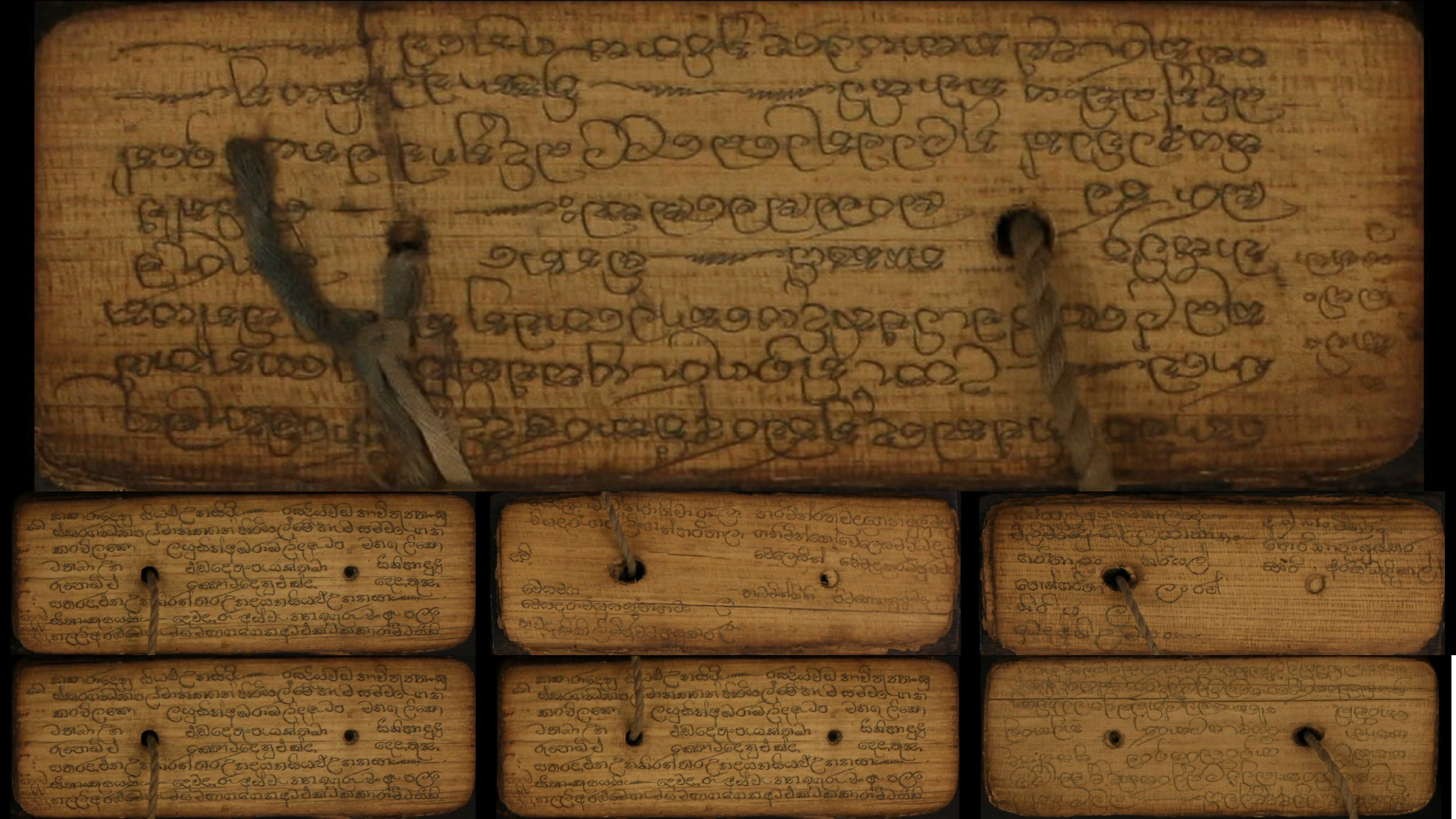

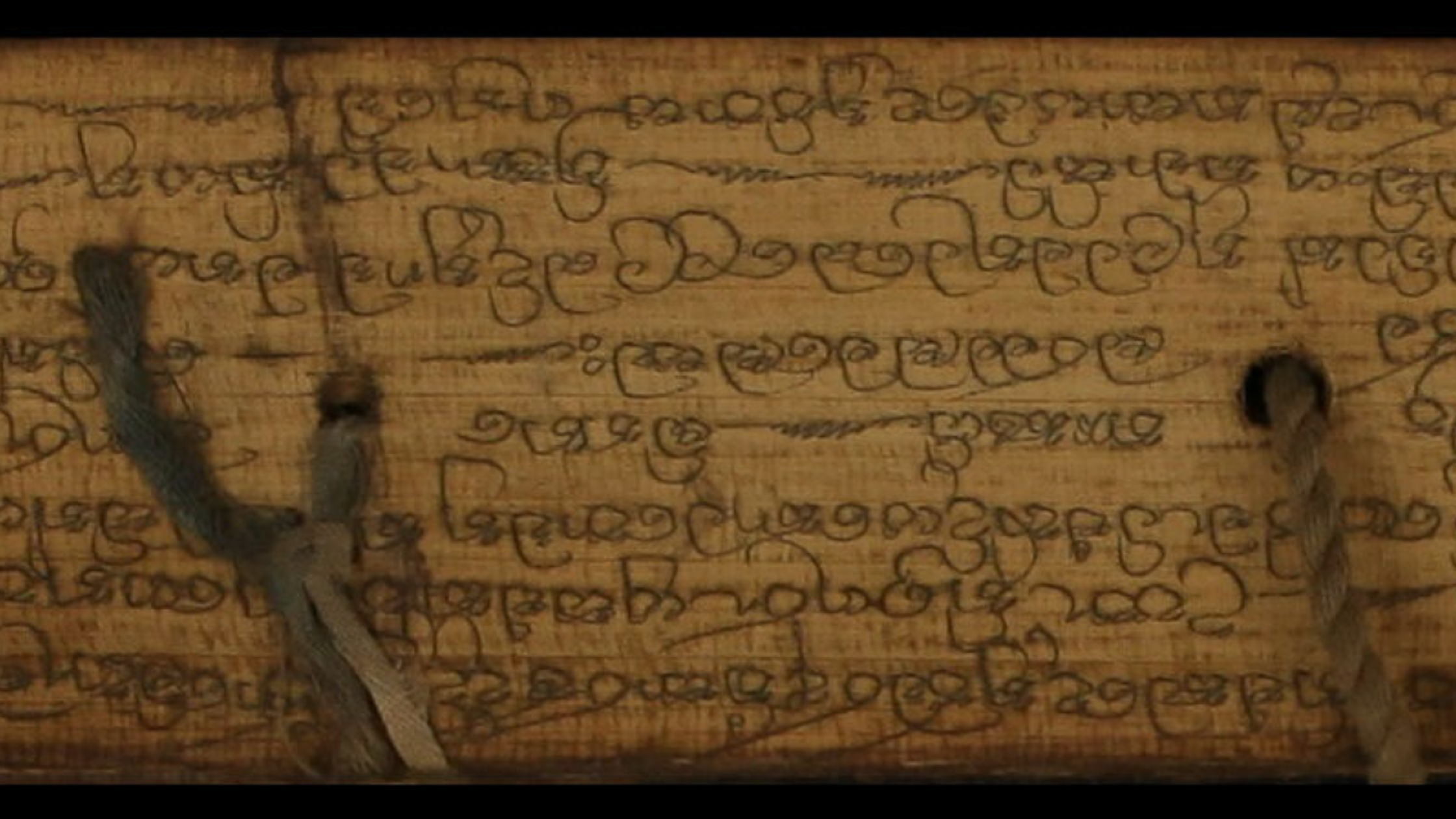

The manuscript comprises a pair of wooden covers bound together by string made of natural fibres. Each page is made from trimmed palm leaf with blackened edges and lines of Sinhalese script.

Most Sri Lankan palm leaf manuscripts were written on the prepared leaves of the Talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera). It is one of the largest palms to grow in Sri Lanka ranging in height from 15-35 metres and takes 40-100 years to reach maturity.

The material used was taken from the unopened leaf buds of young trees. Each leaf bud grows to 3 to 7 metres long and can hold up to 100 leaflets (leaf segments). When the leaf bud was about to open it was cut off and slit open. The leaflets were separated and removed one by one. The midribs were removed and the leaflets immersed in a vessel filled with cold water.

The vessel was placed over a slow fire until the water reached boiling point. The heat was reduced and the leaflets were allowed to simmer for several hours. The leaflets then were taken out and allowed to dry for three days in the sun and in the cooler night air for three nights, allowing them to become supple.

Each leaf blade was weighted and pulled up and down over the smooth surface of a cylinder of wood, usually the smoothed trunk of an areca palm (the tall, thin palm that produces betel nut.)

The pages were then cut from the leaves, punched with one or two holes using a steel punch. A bamboo slither was passed through a hole in each page so that all the pages could be held together, singed with a hot iron and burnt to remove irregularities so each page was uniform in length and width.

Writing was done with a steel point style which was sharpened on an oiled stone. The writing then had to be blackened. This was done with ink made from combining fine dust made from charcoal from leaves, commonly cotton plant leaves, with an alluvial resin. The mixture was heated until a black resinous oil was produced. This was rubbed over the manuscript pages with a cloth so that the whole page was covered with black. This was then rubbed away with sifted rice bran, leaving the black resin in the scratched depressions left by the style.

Palm leaf books were not normally illustrated. Once the pages were finished, two covers were produced for them. These were made to size from one of various types of local woods such as ebony, iron wood, val sapu, gammalu, jak or milla. The leaves and the covers were strung together with either a cotton cord or one made from the fibre of the niyanda leaf.

'South Asian Heritage Month runs from 18th July – 17th August and seeks to commemorate, mark and celebrate South Asian cultures, histories particularly the intertwined histories of the UK and South Asian communities and how South Asian cultures are present throughout the UK and indeed London. The month begins on the 18th July, the date that the Indian Independence Act 1947 gained royal assent and ends on the 17th August, Partition Commemoration Day.'

City Hall blog, london.gov.uk

To celebrate, the RCP are sharing stories of medical professionals of south Asian heritage, working and living in Britain. Read the first story here.

The RCP Museum are also sharing via our Facebook and Instagram some interesting south Asian connections in our collections, like this Sri Lankan manuscript, and our inspiring physicians throughout the month.

Pamela Forde, archivist

References

- De Silva, W.A. Catalogue of Palm Leaf Manuscripts in the Library of the Colombo Museum. Colombo: Colombo Museum, 1938.

- Three exceptional Sinhalese palm leaf (Ola) books and covers, https://www.michaelbackmanltd.com/archived_objects/palm-leaf-books-from-sri-lanka-ceylon-ceylonese/ [Accessed 28 July 2020]