For many years, any suggestions of same-sex attractions or relationships were usually minimised in official documentation such as RCP biographies of its fellows. But that doesn’t mean those loves and relationships weren’t there.

Following the 2018 exhibition ‘This vexed question’: 500 years of medicine, the outer Osler Room wall in 11 St Andrew’s Place was rehung to include a mix of men and women from the RCP’s collection for the first time since the building was completed in 1964. The display includes portraits of two out of three female presidents: Dame Carol Black and Dame Jane Dacre. The third female physician on the wall is a lesser-known figure from RCP history: Dorothy Hare (1876–1967), who was in a relationship with another physician called Elizabeth Herdman Lepper (1883–1971).

In Hare’s Inspiring Physicians entry, Dame Albertine Winner (1907–1988) described Lepper as ‘[Hare’s] life-long friend … who was also a distinguished physician’. The two women retired in 1937 and travelled round the world together for 2 years before settling in Falmouth until Hare’s death in 1967.

Hare’s career began as a house physician and a pathologist, and she later became particularly interested in colitis, arthritis and diabetes. She was the third woman to become a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and the first to do so as a physician rather than a paediatrician. Many women specialised in paediatrics, palliative care and venereal disease because these were the few specialties considered socially acceptable for women.

However, during the First World War, Hare’s attention turned towards the miserable plight of girls who acquired venereal disease. In 1916, she and Lepper answered a call from the surgeon Louisa Aldrich-Blake (1865–1925) to every woman on the Medical Register and both went to Malta with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

In 1918, Hare was appointed assistant director (medical) of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Hare’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says:

venereal diseases were rare in the WRNS but rife in the other services. Dismissed from the forces, often ejected by their families, and, if pregnant, refused admission to homes for mothers and babies, they faced poverty and long and painful treatment without rehabilitation.

Winner tells us that Hare:

founded two hostels, with her great friend Berenice d'Avigdor, which catered for pregnant and non-pregnant girls with this disability. In those days the treatment of venereal disease was protracted, unpleasant and not always effective, and no ordinary lodgings or mother and baby home would accept these girls. The hostels therefore fulfilled a real need … until they closed for the Second World War, when the advent of penicillin simplified the long course of treatment formerly needed.

It would for many years have been difficult to think of one without the other and I feel that Lesbia should in some way be brought into the picture, if you think it practicable

A letter in the RCP’s archives reveals more about Hare’s relationship with Lepper. Hare’s nephew, Ewan Hare, was in conversation with Winner about the biography and wrote:

I do not know to what extent a biography should contain connections with other people but in this case I feel that some mention should be made of Dr Lepper, herself a distinguished person, who undoubtedly played a very great part in Dorothy’s life. They had lived together for a long time, both in their joint medical careers and in retirement, and I know that Dorothy was influenced very much by her companionship and wise counsel though I am not sure to what extent their medical careers dovetailed. They were, in fact, inseperable [sic], and Lesbia accompanied her on all her travels. Though I knew Dorothy so well from my youth it would for many years have been difficult to think of one without the other and I feel that Lesbia should in some way be brought into the picture, if you think it practicable, if only with a mention and that Dorothy would have wished this.

As well as including Lepper in Hare’s biography, Winner submitted a photograph of the two women together to Munk’s Roll (as Inspiring Physicians is also known). It is not known why Hare became a fellow of the RCP and Lepper did not. We can speculate that someone known as Lesbia may not have felt welcome in medical institutions such as the RCP. Lepper’s own obituary in the British Medical Journal in 1972 does not mention Hare at all. The photograph encourages us to remember Lepper as a physician in her own right as well as the importance of their relationship with each other.

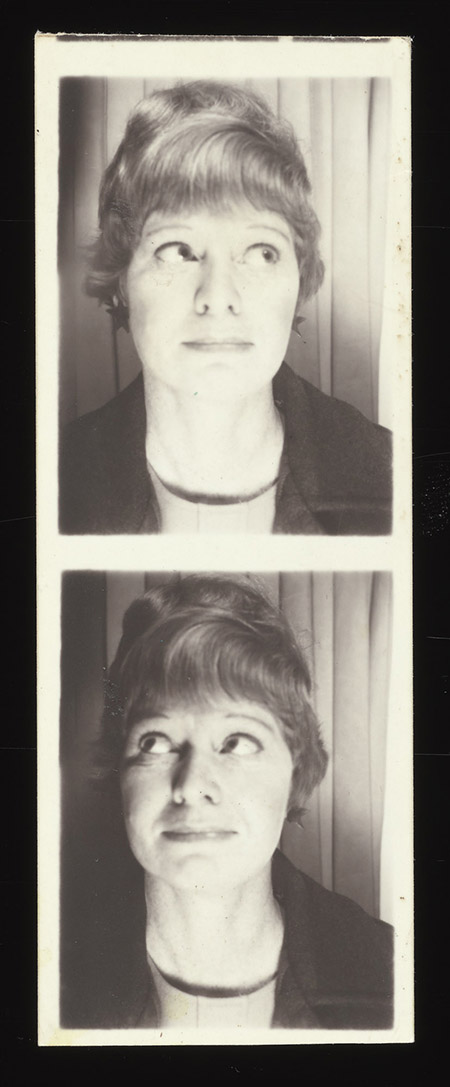

These photographs of Mary Corbett (1933–2009) are unlike anything else in the Inspiring Physicians collection and demand our attention, even though she is not looking directly at us. Corbett appears to be grimacing and in the top photograph she is looking up and to the right and in the bottom photograph, up and to the left.

Reading her biography, she was a highly accomplished rheumatologist, but, as with the description of Elizabeth Lepper as Dorothy Hare’s ‘life-long friend’, it is the last paragraph that stands out:

In her retirement, Mary took up stained-glass making, studied French and travelled extensively with Jean Colston, her friend and companion of 50 years ... She is survived by Jean and by her two sisters, Margie and Sue.

It is safe to say that as with Hare’s ‘life-long friend’, ‘companion of 50 years’ is a euphemism. This couched language was a compromise between acknowledging Corbett and Colston’s enduring same-sex relationship and keeping it safely hidden because of the homophobia that they would have experienced. Corbett’s biography hints at the discrimination she faced by mentioning that she was appointed as a consultant ‘by a then conservative hospital’.

While we use Hare’s painted portrait for her Inspiring Physicians entry, having the photographs alongside the biographies draws attention to the lives of these women that they could not speak openly about. Many such stories are hidden in the biographies and digitising the photographs is encouraging us to look more closely at these women’s lives and bring them out into the light.

Corinne Harrison, LAMS officer

February is LGBT+ history month.