RCP unseen collecting today

RCP Unseen: collecting today

The RCP has never stopped collecting new objects. This section displays some of our recent acquisitions.

In the past, the objects collected often reflected the personal interests of those doing the collecting - as a result, the collections tell their stories well, but leave other important stories out.

Today, we focus on filling the gaps within our collections, so that stories we safeguard are more complete. We hope that in the future the collections will be able to tell the story of modern medicine.

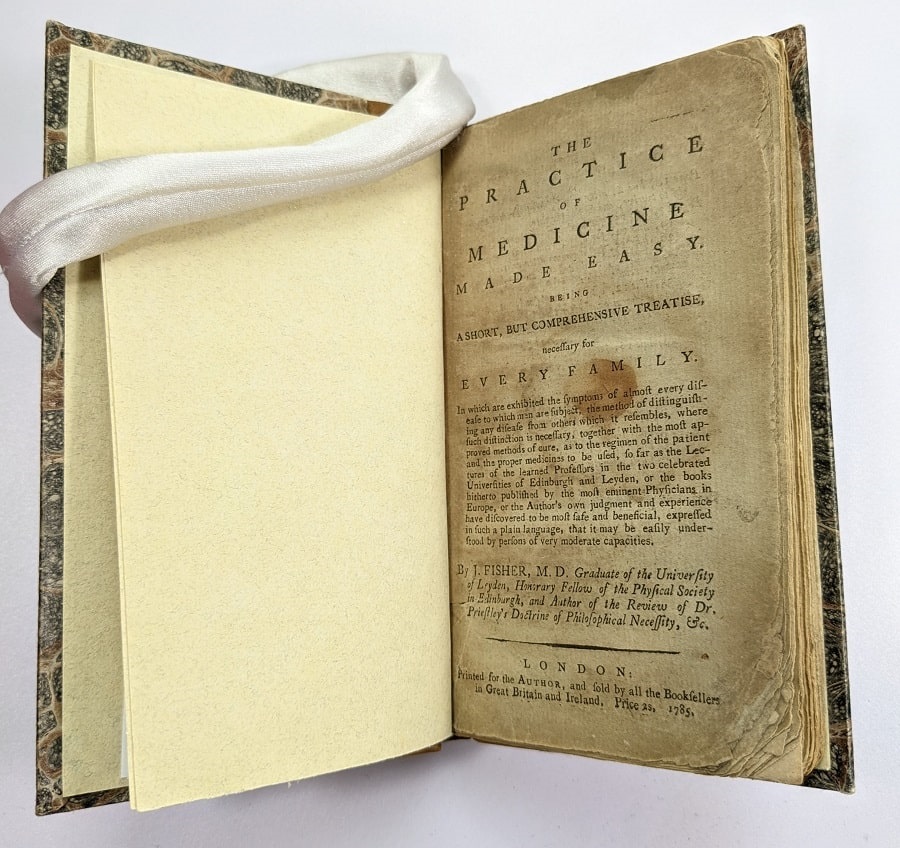

The practice of medicine made easy

J Fisher, The practice of medicine made easy,

London, 1785 (CN120370) When we consider who delivers medical care, we most likely think of doctors and nurses. In fact, most care actually happens at home without professional involvement. This happens especially at times and in places where professional care is inaccessible or too expensive.This book from the 18th century claims to give everyday people all the information they need to preserve and restore their health. It includes recipes for medical remedies for illnesses such as hydrophobia (rabies) and whooping cough.

View the catalogue record for The practice of medicine made easy

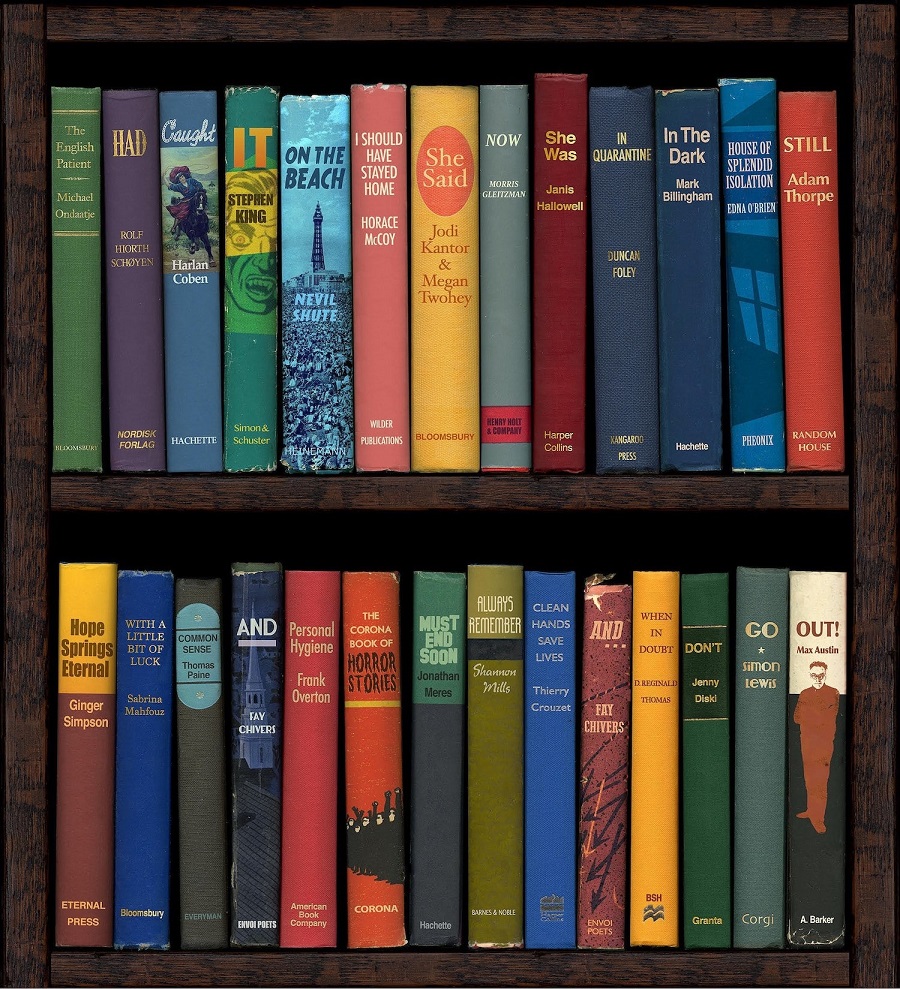

Shelf Isolation by Phil Shaw © the artist and Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Shelf Isolation

Shelf Isolation, digital print by Phil Shaw, 2020 (2020.9)

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenging time for everyone, causing worldwide disruption that is unprecedented in recent times. This digital artwork was created in response to the artist’s experience of living through a national lockdown in the UK, reflecting the struggles of isolation and the importance of basic public health measures such as hand washing.

When read left to right, the real book titles in the digitally created bookshelf reveal a short story. Written in the early stages of the first UK lockdown, the content of the story was intended as ‘a much-needed message of hope’. It could also be read in a more cynical light, with the suggestion that it ‘must end soon’ seeming ironic when the effects of the pandemic continue to have a huge impact on daily life.

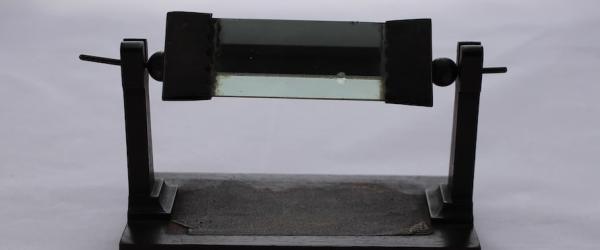

H Renlow, The human eye and its auxiliary organs anatomically represented, with explanatory text, London, 1896

(CN56332)

Highly colourful ‘lift-the-flap’ books such as this were popular in the late 19th century. They were designed to appeal to a lay audience, with little or no medical knowledge.

This eye model includes a special feature. A thin sheet of the transparent mineral mica is used to represent the cornea, the transparent circular part of the front of the eyeball.

Oral history transcript: Professor Sreeharan first western medical school in Sri Lanka

Biography:

Biography:

Nadarajah Sreeharan studied medicine at the University of Colombo in Sri Lanka. Following his junior posts he was appointed as Foundation Chair in Medicine at the University of Jaffna but was forced to leave this position as a result of political turmoil and civil war. He subsequently joined GlaxoSmithKline in the UK, where he spent 20 years involved in the research and development of new medicines as the Senior Vice President and European Medical Director.

Professor Sreeharan tells the story of the first western medical school in Sri Lanka, which was established by an American missionary, Samuel Green:

Transcript:

The first western medical school was set up in a place called Manipay in Jaffna by an American missionary called Samuel Green. I’ve got a photograph here, I can show it to you, that was long before Colombo was set up and it’s interesting these are the first batch of students, would have been somewhere in the early 19th century, so six students. So what is interesting? Two things are interesting, the kit they are wearing, they are wearing the local--, they probably would have been well to do people or they were probably from the indigenous medical background and Samuel Green was the missionary, Christian missionary from Boston, Massachusetts, who initially wanted to go to India but for some reason the Indian government didn’t allow him so he ended up in Manipay in Jaffna in the northern part. The other thing that is interesting is the names of these people, if you look at it. They all have a local name… Valoopilly, Adonansalam, Poopalasingam, and they also have an alias, very English sounding names. And I’m told the English names, are the names -- they take the names of their sponsors, so those are real names of people in Boston who are funding them.

Symons collection of medical and self-care items

Symons collection of medical and self-care items, Europe, 19th century–early 20th century

RCP fellow and cardiologist Cecil Symons and his wife Jean put together an extraordinary medical collection, which they donated to the RCP in 2018.

As well as obviously medical items such as stethoscopes, the Symons collection includes many items that would have been used in the home. In an intriguing contrast to much of the RCP’s collections which show medicine from the doctors’ point of view, the Symons collection shows how domestic care was an important complement to formal medical treatment in the past.

Accepted from Jean Symons under the Cultural Gifts Scheme by HM Government and allocated to the RCP, 2018

Learn more about the Symons collection

1. Leech applicator, England, 1860–1880 (S579.1)

This leech applicator was used to let blood from a specific location such as inside someone’s mouth. One end is narrower than the other to prevent the leech escaping – its mouth would fit through to allow it to bite, but it could not accidentally slip down the patient’s throat. View catalogue entry for Leech applicator

2. Plaster spreader, England, late 19th century (S104)

Before modern sticking plasters, doctors used plaster spreaders to apply a wet mixture of ingredients to the skin. Combinations of clay, oil, oatmeal and various herbs and plants were spread onto the skin or onto a cloth that was then applied to the skin to treat wounds and inflammation View catalogue entry for Plaster spreader

3. Pap boat, England, 1820–30 (S448)

Pap is a mixture of bread soaked in milk or water, sometimes with additions of butter, sugar or other ingredients. It was fed to children or patients from ‘boats’ such as this one. View catalogue entry for Pap boat

4. Tongue scraper, England, 1865–1875 (S376)

Tongue scrapers were a popular way to combat the feeling of ‘furry tongue’. It would be pulled along the tongue to remove any coating or debris, in the same way you would use the ridges you find on the back of some toothbrushes today. View catalogue entry for Tongue scraper

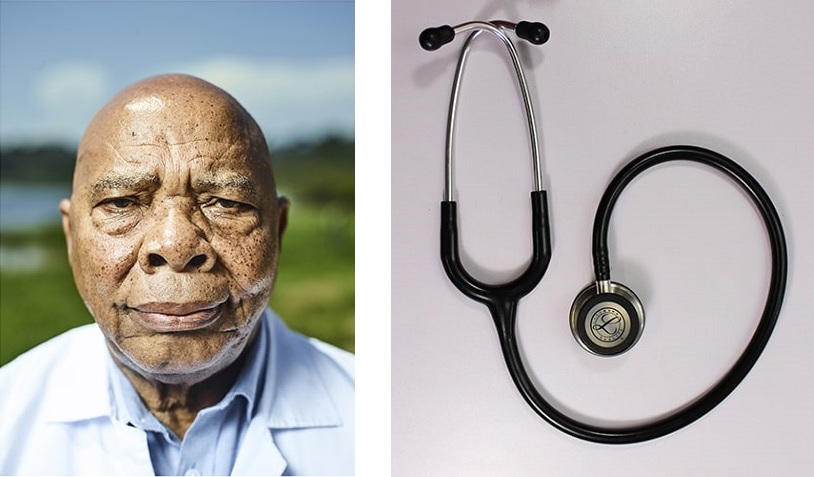

Left : Portrait of Professor Evarist Njelesani

Right: A junior doctor’s stethoscope

Portrait of Professor Evarist Njelesani

Professor Evarist Njelesani (b.1945) C-Type archival print by Jessica van der Weert, 2017 (2018.4)

Professor Njelesani is an influential physician who helped establish the East, Central and Southern African College of Physicians, which works to develop postgraduate medical education in the region.

This photographic portrait is unusual in the RCP collection because it features a Black physician. Every other sitter in the RCP’s portrait collection is White, meaning that the individuals represented do not reflect the full make-up of the medical workforce today or in the past.

As we collect new items today, we prioritise those which show the experiences of physicians who have been previously excluded or overlooked, in an attempt to redress this balance, celebrate their achievements and safeguard their stories for the future.

View catalogue entry for Portrait of Professor Evarist Njelesani

A junior doctor’s stethoscope

A junior doctor's stethoscope, USA, c.2015 (2020.13)

The owner of this stethoscope had trouble using it throughout medical school, finding it difficult to auscultate (examine by listening to) heart and lung sounds. After years of worrying about his hearing, two GP colleagues confirmed that the stethoscope itself was at fault, and the donor has replaced it with a new, more high-tech model.

Auscultation has been a feature of medical training and practise since the 19th century, although some studies have suggested that doctors’ skills in this area are decreasing. New advances in technology can help with this, and some modern stethoscopes include features such as sound amplification, recording and even Bluetooth, which can allow a doctor to examine a patient from a distance – crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic.

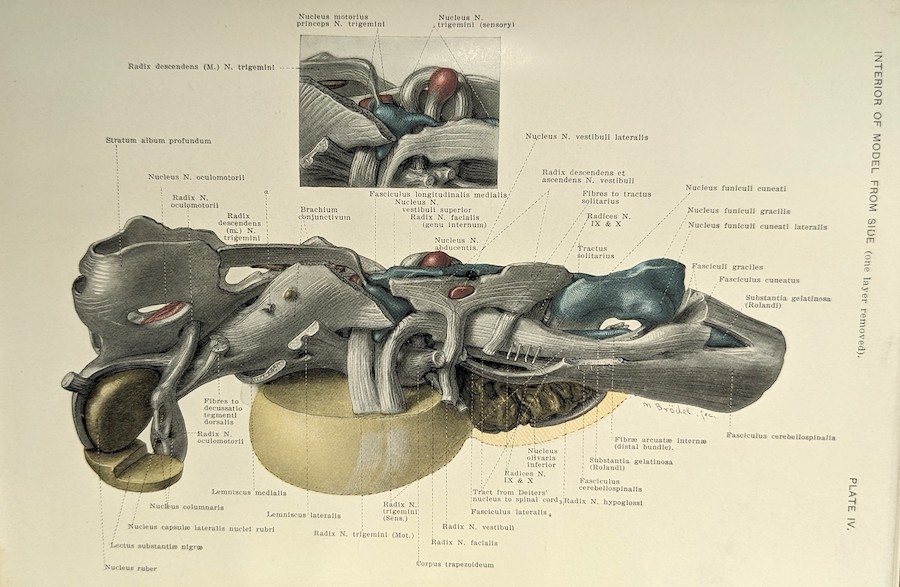

Florence Sabin, An atlas of the medulla and midbrain

Florence Sabin, An atlas of the medulla and midbrain, Baltimore, 1901 (CN56328)

Florence Rena Sabin (1871–1953) was an American anatomist and investigator of the lymphatic system, considered one of the leading women scientists in the United States. Sabin entered Johns Hopkins University Medical School in Baltimore in 1896 and became the school’s first female full professor in 1917.

While still a student, Sabin created a model of the brain stem of a newborn baby, which was widely reproduced as a teaching model in medical schools. The model was made using a wax reconstruction of every alternate slice of a series of horizontal sections of the brainstem. An Atlas of the Medulla and Midbrain, published after Sabin became a professor, gives a detailed account of this model.

View catalogue entry for An atlas of the Medula and midbrain

Part of the exhibition 'RCP Unseen'. Explore further: