RCP unseen doctors and their image

RCP Unseen: doctors and their image

Doctors have been the recipients of honour, criticism, praise and ridicule for centuries. Our collections show that how doctors perceived themselves was often at odds with the public’s perception of them…

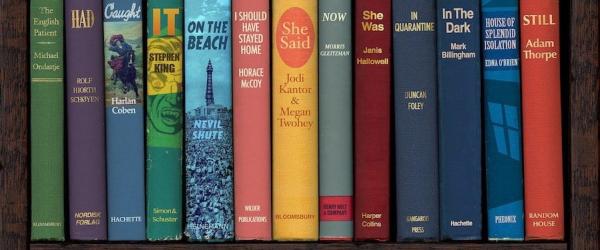

Reproduction of an outfit worn by Richard Mead

Reproduction of an outfit worn by Richard Mead, made by Meredith Towne, Yorkshire 2018

Every aspect of English doctor and collector Richard Mead’s (1673–1754) suit, reproduced from the outfit he wears in a c.1740 portrait in the RCP’s portrait collection, exudes this physician’s wealth and status.

This mid-18th century suit comprises a frock coat, waistcoat and breeches made in a luxurious and tasteful brown silk velvet. The adoption of the fashion for wide sleeves and long coats of this era shows the viewer that the sitter could afford the huge quantity of costly fabric required for the garment. The cravat, frilly cuffs and an overall abundance of buttons similarly indicate that no expense was spared for this physician’s outfit.

Mead also wears a fine wig, perhaps made of human hair or horsehair but definitely not the type of coarse goatshair wigs worn by servants.

View catalogue record entry for the Portrait of Richard Mead

Left: Copper handled drinking cane

Centre: Ivory pomander cane

Right: Softwood country walking cane with hooked handle

The physician's cane

Before doctors became associated with wearing stethoscopes, they often carried a cane. Several physicians are seen holding and sniffing canes in the print ‘The Company of Undertakers’ also in this exhibition (see below). Not just a prop to aid with walking, canes had many functions. Some could conceal liquor [1] or snuff inside for discreet consumption. Others may have contained sweet-smelling herbs [2], to protect the doctor by warding off miasma – a noxious form of ‘bad air’ thought to carry diseases and cause epidemics.

The softwood walking cane [3] appears to be emulating the rod of Asclepius – the serpent-entwined rod wielded by the Greek god of healing and medicine – a very strong and perhaps arrogant statement from its owner.

LEFT: Copper handled drinking cane [1], 1900. (X696)

The shaft of this cane unscrews, and inside it contains a full-length glass brandy flask.

View catalogue entry for Copper handled drinking cane

CENTRE: Ivory handled pomander cane [2], c.1850. (X694)

Pomander canes have a hollow handle where aromatic substances are placed, for doctors to sniff.

View catalogue entry for Ivory handled pomander cane

RIGHT: Softwood country walking cane with hooked handle [3], 1890. (X397)

A carved snake wraps around the shaft of this cane, its head facing towards the handle.

View catalogue entry for Softwood country walking cane with hooked handle

The quack doctor

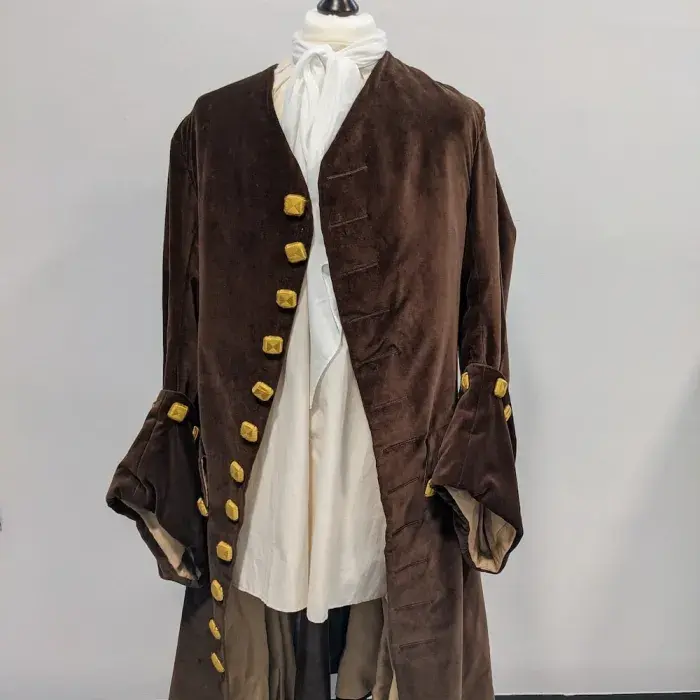

The quack doctor, engraving by Thomas Rowlandson, 1814

(2008.1/12)Death lurks behind the curtain of respectability at this apothecarist’s shop. A skeleton is pounding up a mixture of ‘slow poison’ as he watches a queue of suffering customers in a mirror.

The ‘quack doctor’ behind the dispensary counter may look fashionable and respectable, but the artist Thomas Rowlandson questions the trustworthiness of the pills and powders he is selling. He is stood in front of jars containing poisons such as ‘Arsnic’ and ‘Opium’.

The man and woman languishing in armchairs makes us question if they are going to be healed by these concoctions, especially when the apothecarist’s assistant has other sinister intentions.

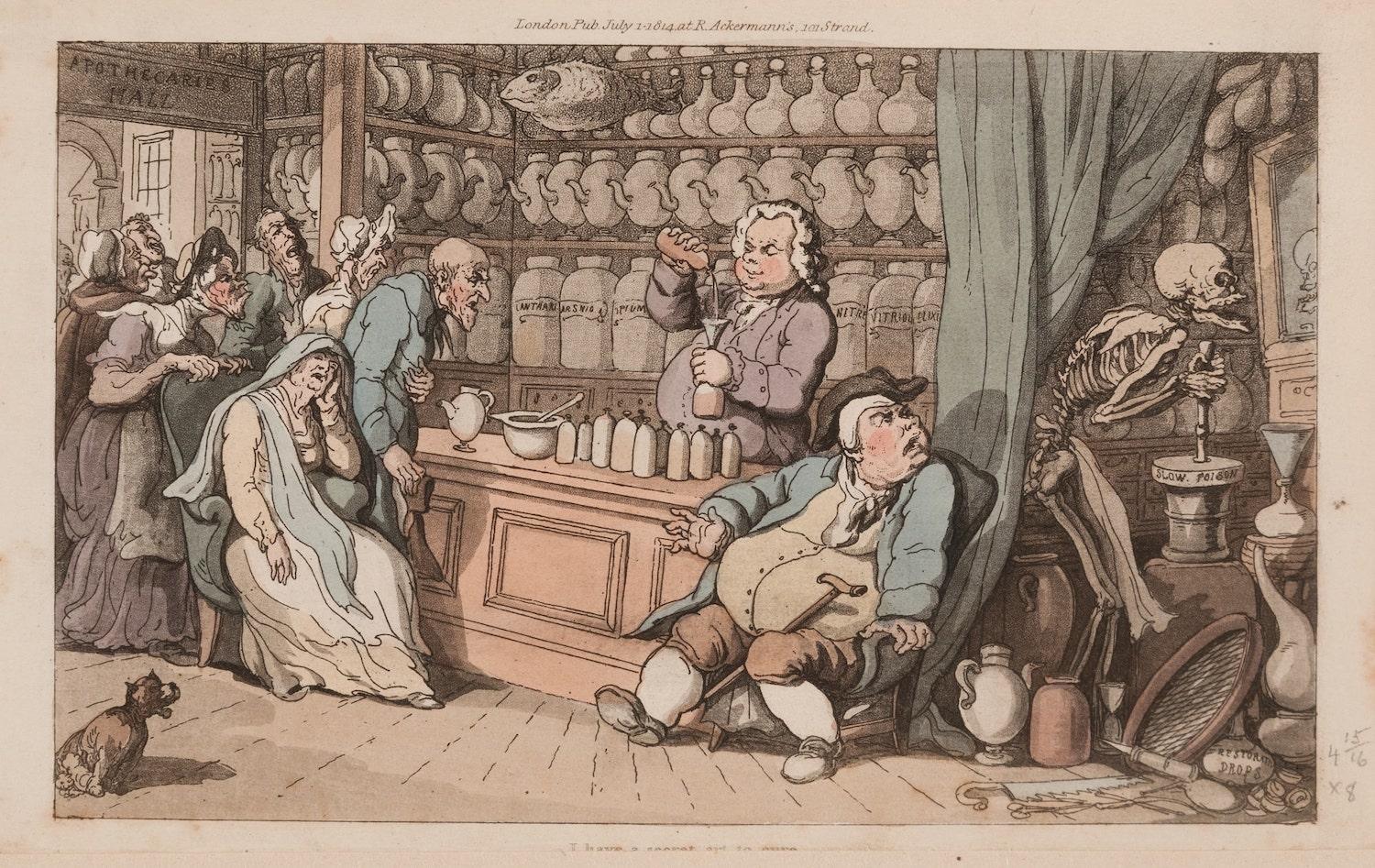

The company of undertakers

The company of undertakers, engraving by William Hogarth, 1736

(PR15014)In this fictional coat of arms, the artist William Hogarth strikes at the public image of physicians.

Twelve bewigged doctors sniff their canes and ponder a flask of urine. Above them sits a trio of quack doctors including an oculist (optician), a bonesetter and a pedlar of cure-all pills. Despite the differences in status, education and regulation between the quacks and the physicians, Hogarth implies that their forms of medicine were equally deadly.

The image is bordered in black like a mourning card. It features a pair of crossbones with the motto ‘Et Plurima mortis imago’ meaning ‘And many an image of death’.

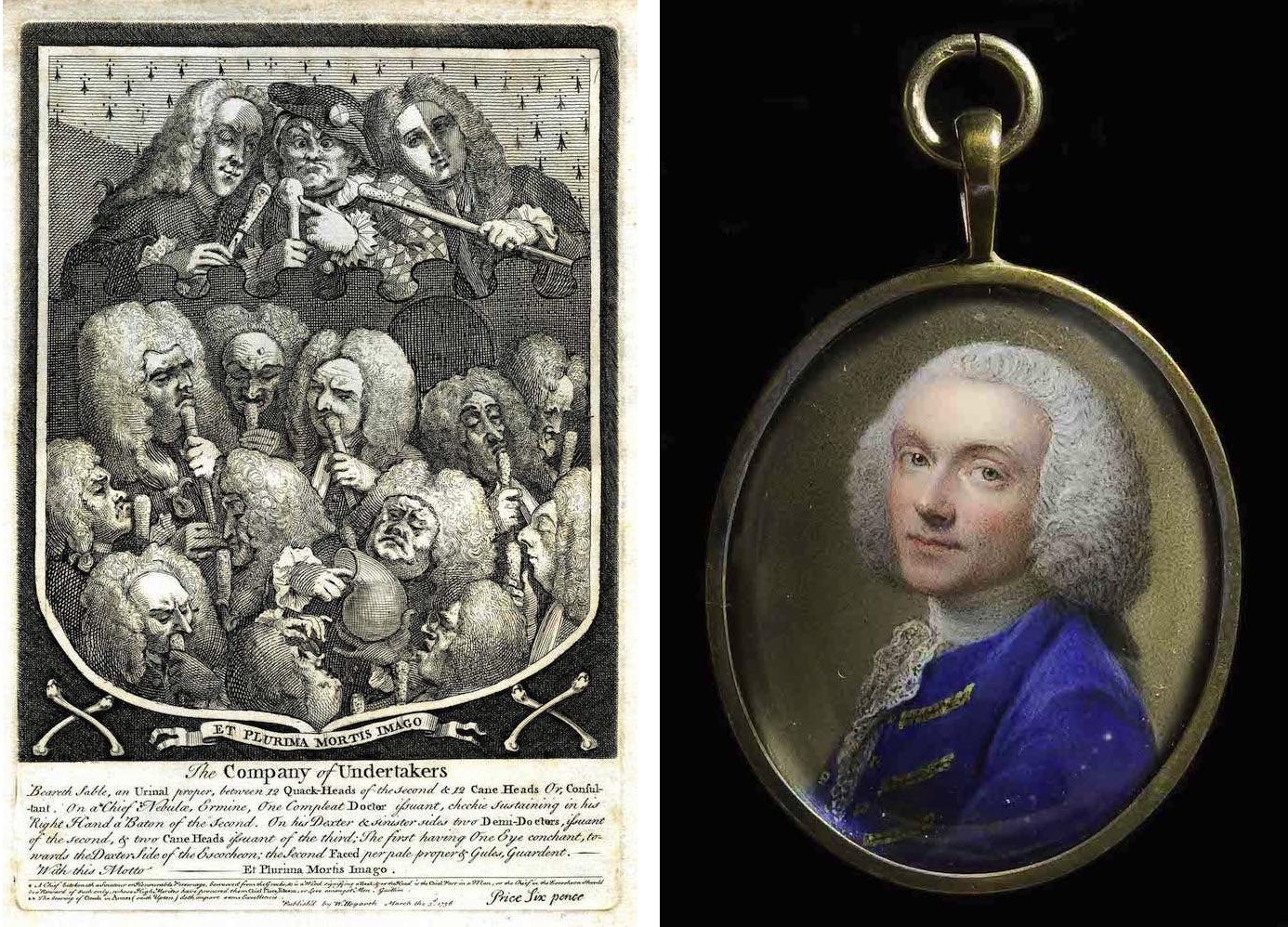

Portrait miniature of William Hunter

Portrait miniature of William Hunter, enamel painting by unknown artist, 1785–1820 (X238)

Exquisitely painted with a vibrant blue coat, the famous anatomist, surgeon and midwife William Hunter (1718–1783) engages the viewer with a captivating expression.

This enamel portrait miniature was painted after Hunter’s death in 1783. Miniatures like this were popular in 18th-century London, and were often given as gifts to loved ones, to express status, and to remember lost family members. Their size allowed them to be held closely and contemplated in private.

In this portrait, the viewer has an opportunity to see how Hunter was perceived by a loved one, or indeed how he wanted to be perceived in private. It presents a contrast to the more familiar public portraits of Hunter, which can also be viewed in the RCP's portrait collection:

Other portraits of William Hunter at the RCP:

William Hunter lecturing at the Royal Academy of Arts by Johann Zoffany, c.1773

Oral history transcript: James Anderson on the qualities of a good doctor

Biography:

Biography:

Dr James Anderson qualified in medicine from Cambridge University. He practised as a physician for ten years before retraining in psychiatry. He then worked as a consultant forensic psychiatrist at the Bracton Centre in Kent before moving to the Practitioner Health Programme, where he treated doctors and dentists suffering from substance misuse and other mental health problems.

Interviewer: Mark Rake.

Transcript:

James Anderson reflects on the sometimes destructive characteristics that many doctors display:

I think that medicine selects individuals who are often highly obsessional, perfectionistic, highly self-critical, because, of course, those qualities make for very good doctors. The difficulty is that if they come under high levels of pressure those personality traits can become very self-destructive because they find that the pressures of work are such that they don't feel they can ever complete anything to their satisfaction, they feel that they are cutting corners and so on and so forth. And they, as I say, are predisposed to being self-critical so they can become extremely distressed because they feel that they are not living up to their own expectations and this can precipitate anxiety and depression.

Oral history transcript: Sir Ian Gilmore on self awareness and belief

Biography:

Biography:

Sir Ian Gilmore studied at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle, and Cambridge University, qualifying to practise medicine in 1971. Following his junior posts he was appointed as a consultant at Royal Liverpool University Hospital where he specialised in gastroenterology and liver disease. Ian is a former treasurer and president of the Royal College of Physicians. Interviewer: John Turner.

Transcript:

Ian Gilmore on the balance between self-awareness and self-belief that is necessary in the practice of medicine:

...Self-awareness is really important... when things have gone badly wrong in technical areas like surgery it’s not because the person can’t tie the knot it’s because they haven’t realised where their boundaries of skill and training ends. So I think to know your limitations is important but that’s a very difficult balance because I think to stand over an anaesthetised abdomen at two o’clock in the morning not knowing what’s wrong with a patient but knowing they’re going to die if you don’t cut them open and do something requires a lot of self-belief as well. So it’s that balance between self-belief and self-awareness of limitations I think is really important in terms of medical safety.

Portrait of Sir Richard Quain

Portrait of Sir Richard Quain, oil on canvas by John Everett Millais, 1896 (X120)

Irish doctor Sir Richard Quain (1816–1898) faces defiantly away from the viewer in one of the last paintings by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais. Unusually for such a large painting of a distinguished physician, Quain appears without attributes or references to his status as a doctor. The purpose of this portrait is unclear.

Quain was an extremely successful physician, and his ground-breaking 1850 paper on fatty degeneration of the heart established him as an authority on the disease. He was vice-president of the RCP, a consulting physician to the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich, and physician-extraordinary to Queen Victoria. Quain also worked as a general physician at Harley Street, where he treated Benjamin Disraeli and many authors, painters and officials.

RCP 500 cycle jersey

RCP 500 cycle jersey 2017–18 (2018.18)

What do the clothes we wear say about us? Traditionally, physicians’ clothes were visual signifiers of wealth and status. This modern physician’s cycle jersey, however, promotes different messages of collaboration and health equality.

This jersey was worn by then RCP registrar (now president) Andrew Goddard during the RCP Charter cycle. Between June 2017 and September 2018, Goddard and his team cycled 2,018 miles visiting acute NHS Trusts and gathering support from fellows and members for the RCP’s modern charter before its presentation to then-president Professor Dame Jane Dacre. The journey also raised funds for Physicians for Africa.

Bejewelled stethoscope, gifted to Professor Dame Jane Dacre (b.1955), John Bell & Croyden, 2008 (2019.2)

Former RCP president and consultant rheumatologist Professor Dame Jane Dacre displayed this stethoscope in her office during her presidency from 2014 to 2018.

The stethoscope was a gift from Dacre’s daughter, after it was used as a prop for the television programme ‘Strictly Come Dancing’ in 2008 where Dacre’s daughter worked. It was used on ‘Strictly’ by actor Tom Chambers, who played a cardiothoracic registrar on the programme ‘Holby City’.

Dacre kept this item as a conversation piece – a deliberately ‘feminine’ challenge to the perceived masculinity of the medical profession.

View catalogue entry for Bejewelled stethoscope, gifted to Professor Jane Dacre

Part of the exhibition 'RCP Unseen'. Explore further: