Related pages

These are a few of our favourite things...

RCP staff pick their favourite items from the current exhibition ‘RCP Unseen’

In the second instalment of our favourite things from the RCP Unseen exhibition, members of the archive, historic library and museum service team talk about their selections.

Lowri Jones, senior curator

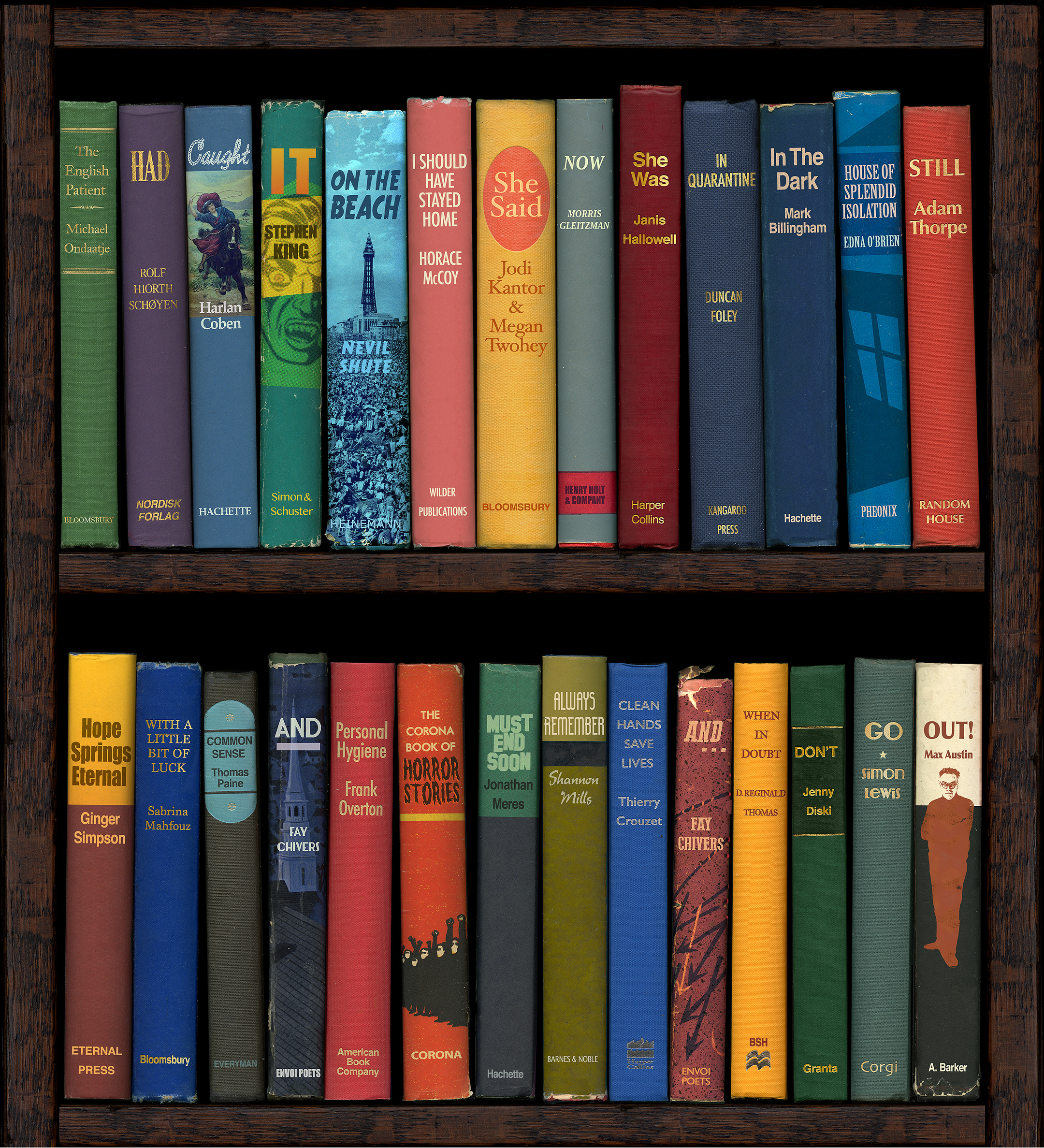

Shelf Isolation, digital print by Phil Shaw, 2020 (2020.9)

There are a few different reasons I chose this print to go into the exhibition:

Firstly, it was new. At the point when we were deciding what to include, we were in the first couple of months of lockdown, and most normal activity had screeched to halt while we figured out how to manage the museum from a distance. During that strange period I was approached by the artist Shaw’s agent, and he and the agent kindly agreed to donate this print to the RCP Museum’s collection. It’s always exciting to share new items, and this was a perfect opportunity to do that.

Secondly, a very simple reason - it’s colourful and bright. It featured in a number of newspaper articles and on social media in April 2020, and its visual appeal probably had a lot to do with this. We were planning an online exhibition for the first time, and I knew that strong visuals would be important – on a personal note, I also just really enjoy the bright, strong colours, which are even more striking when you see the print ‘in the flesh’.

Thirdly, it was really topical. One thing I’m always keen to tell people about, and which you can see in the ‘Collecting today’ section of RCP Unseen where this print features, is that the museum is still collecting. You may think of museums and archives as being full of old things, and you would be right – but they also actively collect modern items, so that the collections can be used in the future to tell the stories of today. This was the first item we collected relating to the COVID-19 pandemic (we are now running a collecting campaign where physicians can share experiences, photos and objects). At the time I liked how this print really reflected the ‘today’ part of ‘collecting today’, and now, almost a year later, I like how it lets us think about the changing meaning of objects. The titles of the real books in the image spell a message, which Shaw intended as a message of hope. One section reads ‘The Corona book of horror stories Must end soon’. While this might have been a positive, encouraging phrase at the beginning of lockdown, I can’t help reading it now with a more cynical tone – it did not end soon. We don’t often get this kind of historical hindsight quite so quickly, and I think it’s a really interesting way of seeing how rapidly people’s thinking about the pandemic has changed over the last twelve months.

My last reason is a bit more practical. When we still thought we would be able to install a physical exhibition in 2020, we prepared all the objects, ready to put them in cases and hang them on the walls. Even though lockdown disrupted the actual installation, the prep work for this print gave the opportunity for the team to do some practical skill sharing. It had been donated unframed, but needed to be safely mounted and framed up to be displayed safely. We purchased the necessary items and one member of the team used this print to train a colleague in how to frame prints to museum standards; a useful skill for future.

Pamela Forde, archive manager

Diploma of Doctor of Medicine, for John (Wallace?), Padua University (MS702)

I chose this diploma because the story behind the forgery is fascinating. In 1618 John Dunbar graduated from one of the top medical universities in Europe, Padua. He returned to England, settling in Plymouth where he practised medicine until his death in 1626. At some point after 1626, a man called John Wallace acquired the diploma and decided to pass it off as his own. However, there are no surviving records of someone of that name practising medicine in England. So, the reason for forging the diploma remains a mystery.

This John erased the surname Dunbaris (Dunbar), and the X in MDCXVIII (1618) to replace them with Wallaceus (Wallace) and XX, to make MDCXXVIII (1628). The surface of the parchment (animal skin) was abraded until the original gold and black ink was removed and the new text was added with black ink.

But the new black ink didn’t match the old and there was no attempt to change any of the names of the University professors who signed the diploma, although several of them had since died. In fact, just under the altered year, the diploma states that this is the 3rd year of the term in office of Johannis (Giovanni) Bembo, Ducis (Duke). Bembo was the Doge of Venice for 3 years, from 1615 to 1618, when he died fighting to free Venice from Spanish occupation.

Elizabeth Douglas, collections officer

Reproduction of an outfit worn by Richard Mead

I chose the Richard Mead reproduction suit for the RCP Unseen exhibition to illustrate the theme of Doctors and their image.

A lot can be ‘read’ into what Mead chose to wear and how he wanted to be seen as a high-status physician.

Mead’s suit is made from an elegant rich brown velvet with no surface decoration, such as colourful embroidery. But make no mistake, a velvet suit could only have been worn by the wealthiest of society. Although Mead is seated, the full skirt of the jacket fills the frame. His wide jacket cuffs are a focal point of his outfit and extend to below his elbow, worn with visible shirt cuffs. A grand number of buttons extend from chest to hem and the scalloped jacket pocket was a very fashionable detail of the time.

The three-piece suit (jacket, waistcoat and leg coverings) remains internationally popular. But by the early 1800s, breeches and stockings were replaced by suit trousers. The frills, ruffs, wigs, buttons and other adornments of this period fell by the wayside within men’s fashion.

If you look at later paintings of the 19th century physicians in the collection, their outfits similarly visually signify their wealth and status but unless they are wearing presidential robes, their dark suits appear like a uniform. They are often without the beautifying adornments and striking silhouettes enjoyed by Mead and other physicians of his generation. More is the pity, as who wouldn’t enjoy swishing around in a full skirted, velvet coat?