When the RCP was founded, its executive body, the Comitia, had the power to not only examine and licence doctors, but also to prosecute them for breaking its rules. Our archives volunteers, Alexa Chamay Berrier and Marcello Goncalves, have trawled through the annals to produce a list of all the doctors who stood before the Comitia in the first century of our existence. Here, Marcello explores some of the stories on the list, which is available to anyone on our website.

By the 16th century, most legally recognized physicians in London were English men who had studied in a limited number of selected institutions, accepted by the newly founded Royal College of Physicians. However, our records show that a much greater diversity of people practised medicine at this time: male and female, English and international, medically licensed and not. The annals of the College provide minutes from the Comitia meetings and give us details of licence issues for certified practitioners or summons for unlicensed practitioners.

Who are these people? Who will you discover? These questions are important to understand the broader history of London and medicine at the time of the Renaissance. We can then explore the different aspects of these cases and how they shape the evolution for the RCP in its founding century.

We can be stunned at first by the range of physicians we encounter here. Physicians who were both respected by their colleagues and remain well-known today feature in these cases. The annals give us a more nuanced view of their career-paths based on their actions. Baldwin Hamey senior, for example, was famous for serving the Russian Czar Fyodor Ivanovich, but other details of his career are less well-known. Did you know that when he moved to London, Hamey had an unlicensed practice and was summoned three times by the RCP before being admitted as a licentiate in 1609? I certainly bet that you won’t see this kind of information on Munk’s Roll!

Some physicians had quite the temperament to fight the RCP establishment: Stephen Bredwell had many moments for us to witness. After becoming a licentiate in 1594, he was summoned for writing slanderous statements about the College’s president and the members, and even misbehaved during Comitia meetings! His absence during the Censor’s Board was also a way to provoke his colleagues, seen by them as proof that he was not a serious physician. The repeated misconduct summons also indicates how the institution tried to treat its ‘difficult’ members.

And this was not exclusive to the registered physicians. Paul Buck was summoned following accusations of unlicensed practice leading him to be imprisoned not just once, but multiple times! In May 1590, he was freed by a warden and escaped, making the College take action against the warden. He was found, accused of unregistered practice, and then sent to prison again. The College had a hard time with some individuals that would break its rules repeatedly. One way to avoid punishment was to simply not turn up to Comitia meetings – in 1588 George Baker claimed he didn’t have time to attend, and wouldn’t even if he did have time. In his letter, he ‘marvelled much how the president dirst be so saucy as to send for him to the College.’ William Forrester (d.1621) is an interesting example as well. Although we have no clear indication of the outcome of these separate events, he was repeatedly summoned after being involved in cases of unsuccessful treatments, as an unregistered physician. These treatments led to the deaths of patients, but somehow Forrester was able to practise again afterwards. What does that tell us about the consistency of the Comitia’s decisions?

The annals reveal much about the different people interacting with the College. One key approach is the social aspect of some of these cases. Alice Leevers was a woman who in 1586 was practising medicine despite the law that only men could practise. She was summoned by the Comitia but was saved by an elite member of the royal court – none other than Queen Elizabeth’s right-hand man, Lord Hunsdon, aka Henry Carey, the Lord Chamberlain of the Queen’s household. A letter from him saved Leevers from possible fees or imprisonment. Indeed, an intervention from the ruling class could save many from the College. Elizeus Bomelins escaped prison after being accused of practising without a license, with the help of an ambassador in 1569, which outraged the RCP. In 1586, John Harris was a French citizen also saved by an ambassador! He was brought back to France following his release from prison after having differences with the RCP.

The cases tell us more about the conditions of contemporary Londoners. In the case of Susanna Gloriana’s unlicenced practice, the College was uncharacteristically sympathetic, and referred her to the French Church in London for support, citing ‘her poverty, her pregnancy and her newborn baby’. Practising medicine was a way to make a living and therefore surviving. The case of Richard Cuckston in 1601 is an example of recorded domestic abuse. Charged by his wife for mistreatment in a medical sense, Cuckston had to pay a fine of £5 and then was sent to prison. It is interesting to see that from a dangerous treatment handled by the College, the data of the annals exposes realities of domestic life from the time.

A big factor of prowess in the medical field is the diversity of perspectives on different practices. At the time of its foundation, the RCP favoured English men that had studied primarily at either Oxford or Cambridge Universities. But the 16th century was a time of big political and cultural changes in Europe, with immigration as a natural consequence. From the case of Gerard Gossen, we hear the plea of a man from the Netherlands fleeing the Duke of Alva, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo. Or William Delaune’s case, where the College questioned him about his unlicensed practice, and the French theology professor confessed to be of Protestant faith, fleeing from persecution. In 1600, Peter Chamberlen (Senior) was also a medically skilled French Huguenot accused of practising without a licence, but who gradually established himself with the College with time. It is very interesting that his son – Peter Chamberlen the Younger – followed in his footsteps and also became a physician at the RCP, their family contributing to the English approach to midwifery.

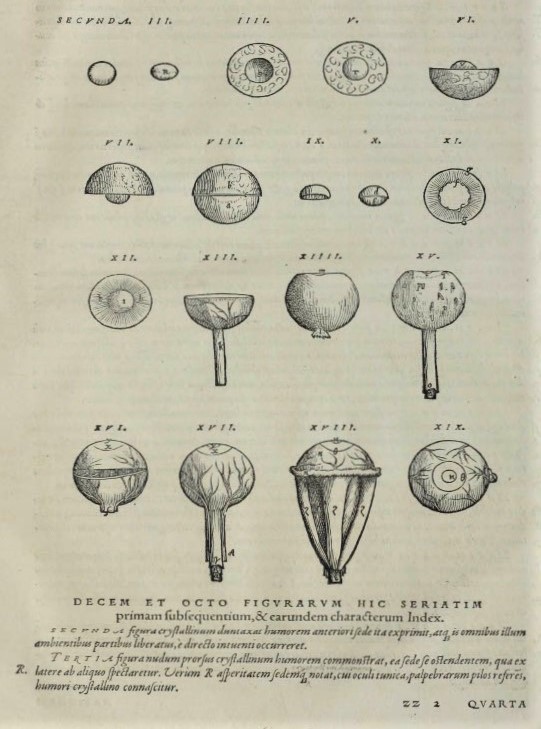

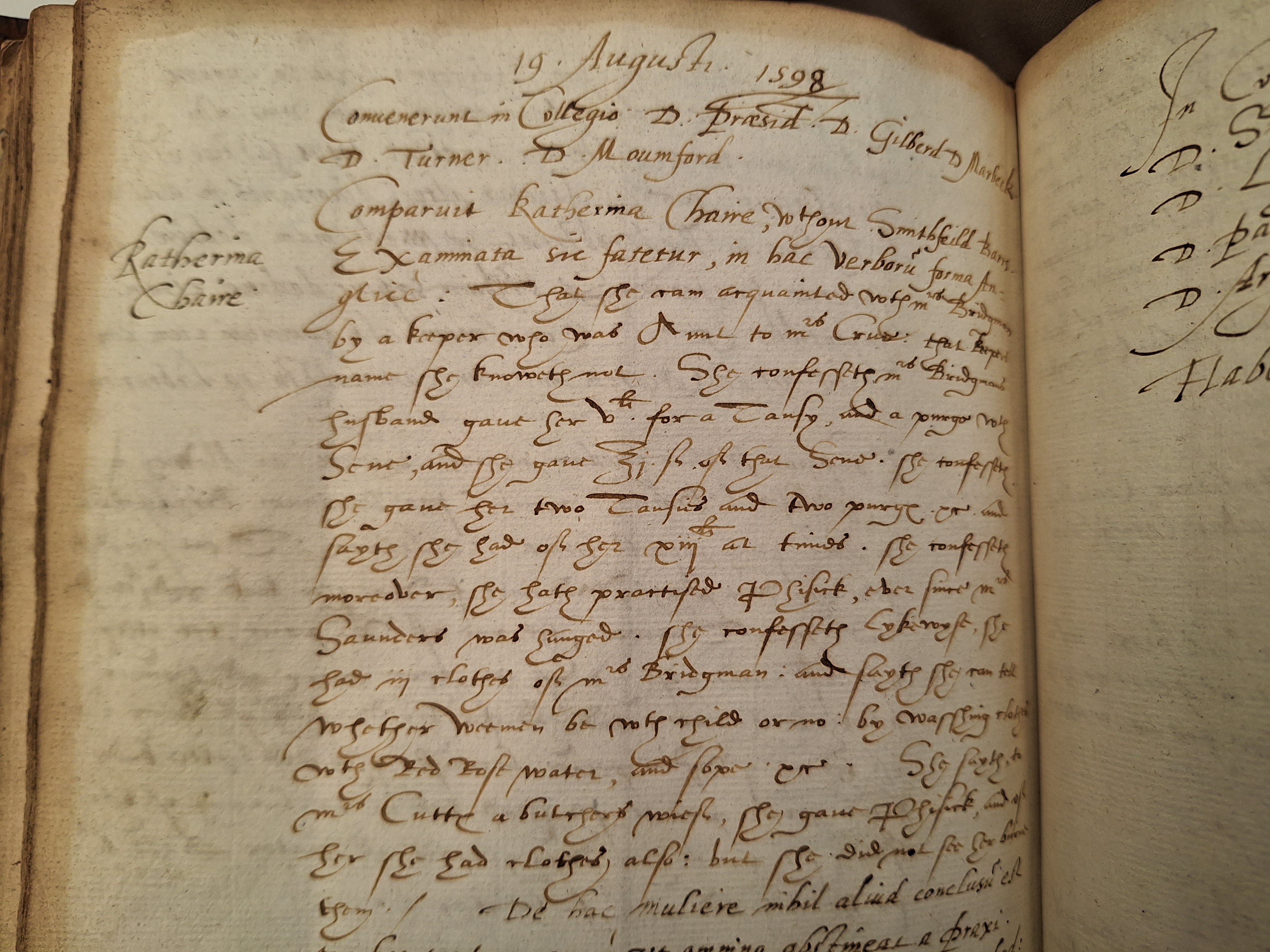

And from here we can peek at the cases and wonder about their medical aspects. The minutes of the Comitia meetings don’t necessarily give clear explanations regarding the decisions made; therefore, we are at liberty of interpreting what we read. Can John Luke be considered as one of the first English eye specialists? In his case, he was granted a medical license in 1561, but only to use for external medicine and only treat ‘eye diseases’. This is fascinating as eye anatomy was explored in this context of ‘rebirth’ of medicine and science. The exploration of understanding medicine led however to mistakes and misinterpretations. Katherine Chaire had her own method of testing a woman’s pregnancy in Smithfield by washing her clothes in red rose water! These interpretations can show signs of too much creativity, which the College disapproved of.

The relationship between physicians and apothecaries was important to help define their separate roles, but ultimately, they were both reliant on each other. Richard Edwards was an apothecary accused of practising without a license in 1601. Apothecaries could not perform the same duties as the physicians but many still practised medicine. John Lumken excessively used purgatives and diet pills on some of his patients who had dropsy or rheumatism. The annals divulge more about what types of medicine were used in everyday life. Edward Stephenson took this practice to another level as he prescribed some badly concocted pills (made with vinegar and quills) to a patient, without the approval of a physician. We can wonder about settled regulations regarding pill production, or should we say lack of?

The Royal College of Physicians tries to establish itself as a predominant institution, backed by the royal Tudor court, if we analyse these cases from a cultural and political angle. Indeed, did you know that the RCP had a short feud with Oxford University regarding the ‘medical qualification’ of two men attempting to practise medicine? In a tremendously long correspondence, both institutions debated on the legitimacy and eligibility of those receiving medical degrees from Oxford, regarding David Lawton and Simon Ludford’s competencies put in question in 1556. These cases give us an insight on how the RCP imposed itself as an established authority on English medicine laws, but also how it interacted with other academic colleges during that time. The case of John Genes is also quite fascinating, where a man spent three days arguing with the Comitia about Galen’s teachings, confronting the College about education and medical ethics! He was summoned as if put on trial, only to apologize and refute his claims. These power-dynamics have an impact on the cultural mindset of the time, and primarily the knowledge of medicine.

Beyond theory, the RCP also had to exert some physical force to showcase its authority to contemporary London society. As seen with John Chandler in 1569, who used dangerous pills in his treatments, the RCP had to act quickly and asked the Queen to prohibit the sale of these pills. This quick royal intervention affected the medical commerce at a low scale but effective enough to demonstrate the RCP’s political influence! And although the College was not an official court of law, it did hold some kinds of trials regarding the discipline of medicine. Have a look at Roger Jenkins’ long list of appearances before the Comitia, facing multiple accusations over the span of twenty years! The Comitia had a voice and the ability of sending people to prison or impoverish them.

Marcello Goncalves, archives volunteer

Find out more: