Our exhibition ‘Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity’ includes dozens of books and drawings, as well as contemporary artworks by 14 different artists. But there are also lots of items on permanent display throughout the RCP museum that demonstrate how the human body has been treated by medicine in the past.

The new anatomy-themed museum trail allows visitors to our Regent’s Park building to choose their own route through our selection of 15 paintings and objects, all of which complement and expand on the themes in the exhibition.

Physicians learning anatomy

Two portraits in on display demonstrate the importance to physicians of getting a good grounding in anatomy. An unidentified physician is portrayed sat in front of his bookshelf, which includes the work of Andreas Vesalius alongside other classic medical texts. Sir Charles Scarburgh’s portrait prominently displays an anatomy book, open to an illustration of the human muscles, on a table laid out in front of the sitter.

Teaching anatomy

RCP fellow William Harvey used a whalebone and silver rod as a pointer during his anatomical lectures. As the RCP’s Lumleian lecturer, Harvey dissected human bodies in front of an audience of physicians and surgeons.

In the 17th 18th centuries, the RCP had its own anatomical theatre, a specially-designed space used for dissecting bodies in front of an audience. The college had since 1565 had the legal right to use the bodies of executed criminals for this purpose. The anatomical theatre was added to the RCP buildings on Warwick Lane, in the City of London, in the 1670s.

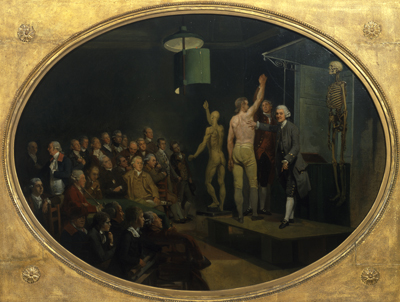

Anatomy has long been taught to artists as well as medical professionals. The physician William Hunter was the first teacher of anatomy at the Royal Academy of Arts, and a painting by Johann Zoffany records him giving an anatomy lecture. Hunter is show using several tools to aid his teaching: a mounted skeleton is displayed at the back of the stage, a live model is posing to show the muscles of his back, shoulder and arm, and to the left of the stage there is an écorché model in the same pose. An écorché is a plaster cast taken from a dead body that has been flayed to remove the skin and expose the muscles, used by artists as part of their training in anatomy.

Putting women in the picture

Women’s bodies are rarely included in anatomical illustrations unless specifically to show female reproductive anatomy. However, two of the RCP’s six anatomical tables show women’s bodies without focussing on their wombs. The tables preserve human remains arranged to look like anatomical illustrations on boards of wood. These two tables show the arteries and veins. We don’t know anything about the women whose bodies were dissected to produce these tables. Their identities either weren’t recorded at the time, or they have been lost subsequently.

Women’s bodies are represented very differently in Chinese medical dolls. These small figurines, known as diagnostic or ‘modesty’ dolls, are said to have been used by women patients – or their servants – to indicate to a doctor what and where their symptoms were. This would have provided an alternative to an embarrassing or culturally prohibited physical examination by a male doctor.

It is striking that an object intended to protect a women’s modesty shows a woman’s body in a sexualised pose, with exaggerated breasts. Although supposedly an object with medical use, it has very little anatomical detail, and the precise use of the dolls has been questioned, suggesting that they may been made as collectible items for the Western market.

Using bodies after death

Human bodies haven’t always been used in very respectful ways after death. It seems macabre today, but human remains were once suggested as ingredients in medicines, alongside the more common plant, animal and mineral components.

In 1618, the Royal College of Physicians published an official book of medical recipes, the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis. It included a long list of possible medical ingredients, including human fat, urine, blood and bone, and these frequently appear in English translations and adaptations of the book as well as in the Latin originals. These ingredients were believed variously to help joint pain, paralysis and epilepsy.

RCP fellow Theodore de Mayerne (1573–1655) prescribed an ‘arthritic powder’ to his patients suffering from the joint disease gout. The powder was made from several different plants and herbs, white wine, and shavings from a human skull that had not been buried. Mayerne noted that if a patient objected to consuming human remains, shavings from the skull of an ox could be used instead. Mayerne was painted holding a human skull, which may or may not have been a reference to this medicine.

Henry Halford (1766-1844) was the RCP’s longest-serving president, who lead the college for 24 years from 1820 to 1844. He was famously reluctant to physically examine the bodies of his patients, but apparently didn’t show the same distaste for handling dead bodies.

In 1813 he was invited to investigate a coffin discovered in Westminster Abbey in London. The skeleton inside was found to be the remains of King Charles I, who had been executed by beheading in 1649. Halford is rumoured to have kept one of the neck bones from the body, that one which had a mark on it from the executioner’s axe. It was even said that he brought this bone out as a talking point at dinner parties.

Medical collectors

Other physicians collected specimens from more recently deceased people. Both Matthew Baillie (1761–1823) and Robert Hooper (1772–1835) kept large collections of pathological specimens, which they used for teaching and research. Both published important books on the subject.

Baillie gave his collection to the Royal College of Physicians in 1818, and they were later transferred to the Royal College of Surgeons in 1938. Sadly, the specimens were destroyed during the bombing of London in the Second World War.

Robert Hooper was painted as if sat at work at his desk, one of his (possibly animal) specimens lurking in the darkness behind him.

All of the objects on the museum trail invite visitors to think more deeply about why, how and by whom human bodies have been used in the service of medicine. It reveals extra depths and details in objects that have long been displayed in the museum.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

- The exhibition ‘Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity’ runs until 3 April 2020.

- The RCP museum is usually open Monday–Friday, 9am–5pm. Please check online for details of occasional closures.

- Pick up a museum trail leaflet around the building or download a copy online and explore the four floors of displays.