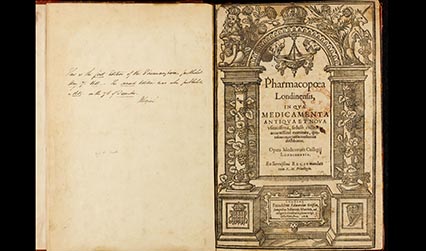

The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis – one of the RCP’s most important publications – is the curator’s curiosity, on display until 20 June 2018.

The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis represents one of the most significant achievements for the Royal College of Physicians in its 500 year history. In her book Grave and learned men: the physicians, 1518-1660, Dr Louella Vaughan describes the Pharmacopoeia as ‘…a mighty weapon dressed up as a book.’

The power of the Pharmacopoeia londinenisis

The Pharmacopoeia was the first of its kind in England and was backed up by a royal proclamation from King James I. The proclamation enabled the Royal College of Physicians to create an officially sanctioned list of all known medical drugs, their effects and directions on their use. No one was allowed to concoct any medicine or sell any substance if it did not appear in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis. In other words, if you wanted to practise medicine or sell drugs in England, then you had to do so on the Royal College of Physicians’ terms.

The College and the Society

The timing of the publication of the Pharmacopoeia was significant. In 1617 the king had created the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. For the best part of a century since its foundation in 1518, the college had retained an element of control over the apothecaries through their regulatory powers. The college annals are full of accounts of apothecaries being fined or imprisoned. The college also had the power to inspect apothecary shops in London and to burn or destroy any drugs being sold which the physicians deemed unsuitable.

The creation of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries dealt a significant blow to the college’s control of the apothecaries. Although the College retained the right to licence all apothecaries in London, they could no longer prevent them from practising medicine or limit them to only dispensing treatments that had been prescribed by a College physician. The Pharmacopoeia allowed the College to regain some of the control that was lost in 1617.

The Pharmacopoeia didn’t have an easy birth. The College had first started planning the work in 1585, some 33 years previously, and the version published in May 1618 was quickly superseded by a revised edition, issued within a year.

St John’s Wort, fox lungs and iatrochemistry

The ingredients and medicines included in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis represent standard medical practise of their time. Some – such as oil of St John’s Wort – were popular herbal remedies then and even now. Others – such as linctus of fox lungs – seem strange to contemporary eyes, though they were back by the medical theory of the 17th century. The Pharmacopoeia also revealed some of the tensions in the medical establishment at the time. Some physicians were starting to question the value of long-used herbal and animal remedies, based on the teachings of 2nd-century AD Greek physician Claudius Galen, and they were recommending chemical treatments instead. One of these so-called ‘iatrochemists’ was Sir Theodore de Mayerne (1573–1655), who was involved in compiling the Pharmacopoeia and included two short sections of chemical medicines at the end of the book.

The authority of the Pharmacopoeia and of the College itself was dealt a blow in 1649 when Nicholas Culpeper published an English translation of the book, under the title The London dispensatory. Not only did Culpeper’s book render the Latin names of substances and methods of preparation into a language spoken by more of the population, Culpeper also included the descriptions of the uses of the different preparations, omitted from the physicians’ book.

The end of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis

The Pharmacopoeia was evidently a successful publication for the college, with a total of nine editions being published between 1618 and 1718. It was not until 1864 with the publication of the British Pharmacopoeia, which combined the London, Edinburgh and Dublin pharmacopoeias, that the college stopped publishing their own version. By the 19th century however, the more outlandish ingredients, such as goat’s urine for deafness, or moss taken from a human skull, had thankfully been removed long ago.

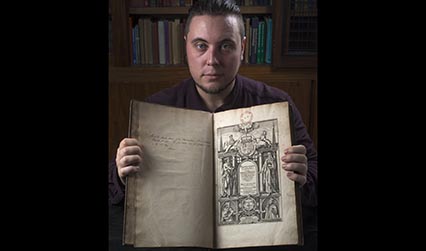

Matthew Wood, exhibitions officer

In celebration of our anniversary year, the RCP Museum team has developed a new heritage trail called Curator’s Curiosities to share with the public some of the more curious stories behind our special collections. Alongside special purple signs around our Regent’s Park building, we are featuring monthly rotating displays of treasures from our stores which are rarely exhibited.

- Visit the RCP and see the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis displayed in the Treasures Room until 20 June 2018.

- The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis is the subject of a new book, Pharmacopoeia Londinensis 1618 and its descendants, by Clare J Fowler, available now for pre-order.