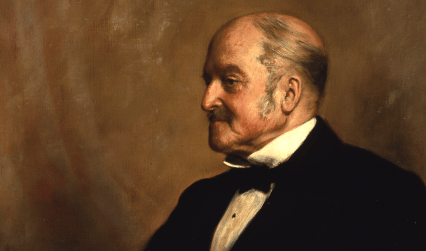

Munk’s Roll, also known known as the 'Lives of the fellows', is a series of obituaries or biographies of fellows of the Royal College of Physicians. It was first compiled by physician William Munk (1816–1898) and is still maintained today.

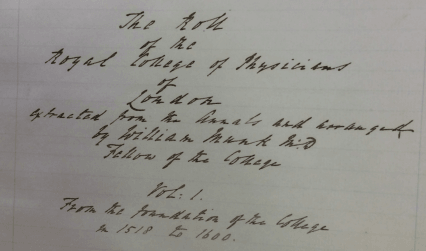

In March 1855, William Munk (1816–1898), a London physician specialising in smallpox, presented a large leather-bound volume to the library of the Royal College of Physicians. This was his Roll, a painstakingly-researched collection of biographies of fellows, licentiates, candidates and extra licentiates from the foundation of the RCP in 1518 to 1600, written by hand on ruled paper in his own distinctive script. In December of the same year, he presented a second volume, covering the period from 1601 to 1700. And in June 1856, the series was brought up to 1800 with the gift of a third book.

Although he had only been elected a fellow of the RCP in 1854, Munk was appointed as Harveian Librarian in 1857, a post which had been left vacant since the death of Richard Tyson in 1750. There is nothing in the records at the RCP to indicate why he was chosen, but Munk’s proven interest in the history of the RCP probably made him an obvious choice.

Munk never intended the Roll to be published. However, on 9 November 1860 the RCP treasurer, Sir James Alderson (1794–1882), wrote to him saying a ‘wish had been expressed by some influential Fellows of the College for the publication of “The Roll”’. As is recorded in the first published edition, in December 1860 the comitia (the RCP’s annual general meeting) ‘resolved … that the College Roll be printed under the direction of Dr Munk the Harveian Librarian and at the expense of the College’.

Two volumes were printed and published in 1861: the first covering the period 1518 to 1700 and the second from 1701 to 1800. A second revised edition, in three volumes, was published in 1878. In this expanded Roll, Munk brought the biographies up to 1825, the year the RCP moved into its new building at Pall Mall East.

In the same preface in the first volume, Munk apologises for a lack of precise references and admits having ‘destroyed in 1857 most of the memoranda upon which my sketches were founded’. Presumably he spent his spare hours writing letters to contacts around the UK, gathering information. We do know that, like many Victorians, he was a keen letter writer; he received and replied to many enquiries after the Roll had been published and some of these later letters survive.

Munk also states in the preface that he used several publications to compile his biographies, most of which would have been available in the RCP Library. These are:

-

Athenae Oxonienses. Anthony à Wood, published London, 1691

-

Bibliotheca Britannica: or, a general index to British and foreign literature. Robert Watt, published Edinburgh, 1824

-

The lives of the professors of Gresham College. John Ward, published London, 1740

-

Biographia medica. Benjamin Hutchinson, published London, 1799

-

Biographical memoirs of medicine in Great Britain from the revival of literature to the time of Harvey. John Aikin, published London, 1780.

Munk also says he used catalogues of Oxford, Cambridge and Edinburgh medical graduates, ‘county histories’, ‘biographical dictionaries’ and ‘that invaluable repertory of biographic lore The Gentleman’s Magazine’.

In the second edition, Munk adds to his list the Annals (the official records of the RCP), Baldwin Hamey’s Bustorum aliquot Reliquiæ, which contains 54 medical biographies (and is described by Munk as ‘one of the most interesting MSS. in the College’) and the Harveian orations. He also admits he is ‘indebted to the Lancet and the Medical Times and Gazette’.

Perhaps because they were never intended for publication, Munk’s ‘sketches’ are sometimes oddly idiosyncratic. Munk was not averse to giving his personal opinion of his subjects. In volume one, a Bath physician, Reuben Sherewood (d.1598), is described as having ‘left behind him the character of a ripe scholar, an excellent physician, and an eloquent man’. Nor did Munk shrink away from plain gossip: Robert Huicke (d.1580), for example, ‘was not happy in his domestic life, but the fault seems to have rested with himself’. Munk goes on to give details of the legal case between Huicke and his wife.

Munk also indulged in some self-censorship – he didn’t always include everything he knew about his subjects and the internal politicking at the RCP. For example, he recorded that Gerard Boet (b.1603) was licensed in 1646, but didn’t mention the other 28 entries in the Annals about Boet, which record the RCP’s prosecutions of him for illegal practice.

While the Roll sometimes reveals the quirks of Munk, it is also a product of a particular time and place: mid-19th century Victorian England. The idea of writing biographies of notable figures was not new: Munk had, after all, found a series of books in the RCP library which described the lives of their subjects. As an educated Victorian, he may have read Brief lives by the 17th century historian and biographer, John Aubrey (and was perhaps influenced by its gossipy style). And there was even a precedent for the idea of biographies of fellows of scientific institutions: the Royal Society had first published obituaries of its fellows in 1830. These were initially read at the annual meeting and then printed in its Proceedings.

Munk was writing in an era which saw the rapid expansion of cities, ever-growing industrialisation and increasing scientific knowledge, all explained by the self-congratulatory idea of ‘progress’. Munk must have begun researching his Roll in the years just following the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Hyde Park showcase which celebrated ‘modern’ technology and design. And, although Charles Darwin’s On the origin of species was not published until 1859, ideas about evolution were emerging as gentleman scientists and amateur naturalists tried to reconcile what was said in the Bible with the evidence increasingly being recorded in the natural world.

In writing the Roll, Munk may then have been motivated to record the progress of medical knowledge over the 300 years of the RCP’s existence. In volume one, he described how John Geynes (d.1563) dared to doubt the ideas of Galen:

The year before his admission as a Fellow, he was cited before the College for impugning theinfallibility of Galen. On his acknowledgement of error, and humble recantation, signed with his own hand, he was received into the College. This incident, [was] curiously illustrative of the state of medicine in this country at that time.

Munk marks several scientific ‘firsts’: Thomas Penny (d.1589) was ‘one of the first Englishmen who studied insects’ and John Craige ‘was probably the person who gave Napier of Murchieston the first hint which led to his great discovery of logarithms’.

But there was another side to mid-century Victorian culture: Romanticism and a turning back to a supposed ‘Golden Age’. In the 1850s, the art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) was promoting and encouraging the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of painters who looked back to Raphael and earlier artists for inspiration. In the same period, the new Parliament building, designed by Charles Barry (1795–1860) and August Welby Pugin (1812–1852), was being constructed in a Gothic, medieval revival style.

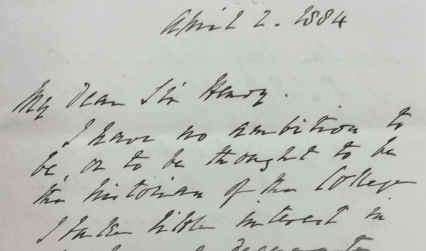

Munk certainly thought the Golden Age of medicine and the RCP was in the past, and his biographies can be seen as a celebration of this bygone age. Asked if he knew anything about a contemporary physician, Dr LP Madden, he explained (in a letter dated 2 April 1884) he had ‘little interest in the present degenerate race of physicians’.

The irony is that Munk himself would not have been elected a fellow in this ‘Golden Age’. Born in Battle, Sussex, the son of an ironmonger, he studied at University College London and gained his MD from Leyden. He converted to Catholicism in 1842. Until 1835, fellows of the Royal College of Physicians had to be graduates of Oxford or Cambridge, universities that only admitted Protestants.

Sarah Gillam, assistant editor, Munk's Roll

The Lives of the fellows continues to be compiled today, and can be searched and read online.

The following sources were used when writing this post:

-

Cooke AM. History of the Royal College of Physicians, Vol 3. London: RCP, 1972.

-

Davenport G, McDonald I and Moss-Gibbons C (eds). The Royal College of Physicians and its collections: an illustrated history. London: The Royal College of Physicians, 2001.

-

Holroyd M. Our friends the dead. The Guardian 1 June 2002. [Accessed 2 April 2017].

-

Munk W (ed). The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London: compiled from the Annals of the College. London: RCP, 1861.

-

Munk W (ed). The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London; comprising sketches of all the eminent physicians, whose names are recorded in the Annals from the foundation of the College in 1518 to its removal in 1825, from Warwick Lane to Pall Mall East, 2nd edn. London: RCP, 1878.

-

Obituary: Dr William Munk. The Times 21 December 1898.

-

Payne LM and Newman CE. Dr Munk, Harveian Librarian: the first period. J Roy Coll Phycns 1977;2:281–8.

-

Payne LM and Newman CE. History of the College Library 9: Dr Munk as Harveian Librarian 2 (1862–1870). J Roy Coll Phycns 1978;2:189–95.

-

William Munk, MD FRCP Lond. Br Med J 1898;2:1914.

-

William Munk (1816-1898): Miscellaneous papers on medical biography including original manuscript of Munk’s Roll c.1850-1889. RCP archives.

-

William Munk (1815-1898). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

-

Wilson AN. The Victorians. London: Arrow Books, 2003.