When returning to the office after months of pandemic-induced working from home, there was a surprise treat amongst the pile of post awaiting my colleagues and I: a package of letters relating to the illness of King George III (1738-1820), kindly donated by the family of John Scott (Lord Eldon) (1751-1838).

George III lived with a mental health condition characterised by episodes of mania – he would become hyperactive and highly talkative, but without always making sense to the person he was speaking to. There is no consensus about the cause of his symptoms, but they may be indicative of bipolar disorder. In his later years, he experienced delusions, for example imagining or holding conversations with people who apparently weren’t there. The treatments that George was subjected to by his doctors were typical of the time, and included purging, blistering, and bloodletting. He was also sometimes made to wear a straitjacket during periods of mania.

George appointed John Scott as Lord Chancellor in May 1801, during an episode of illness. As a senior government official, Scott was responsible for updating parliament on the King’s condition, including, crucially, whether the King remained capable of engaging with parliamentary business and giving royal assent or whether these duties should be passed to his son George, the Prince of Wales. Scott therefore received daily reports from the royal physicians regarding the King’s health and treatment, and it is these reports that make up the bulk of the recent donation.

Our archives already include several records relating to George’s illness, so the new letters complement, and shed light on, our existing collection. Before now, Scott’s only presence in the collection was a brief and catty exchange between him and Thomas Monro (1759-1833), principal physician at Bethlem Hospital. Scott, perhaps feeling obliged to at least appear to involve a supposed mental health specialist, summoned Monro to a consultation with the royal physicians in August, 1811. Monro’s opinion seems to have been that he should be put in charge of the King’s care, something that those close to George had no intention of allowing. Scott wrote to Monro, declining his advice but assuring him that he would let the prime minister know the trouble Monro had gone to. Monro replied, acknowledging Scott’s ‘very polite and condescending note’, and making it clear what he thought of the King’s doctors: ‘it is vain to expect more effectual aid in this truly distressing case than is likely to ensue from the state and experience of his majesty’s present physicians’. This vignette largely sums up the impression I get from this collection as a whole, which is one of a ring of parliamentarians and physicians jockeying for political or professional position, whose least concern was the health and happiness of the patient at its centre.

George III, in important ways, was not a sympathetic figure. As head of the British Empire, he was highly complicit in the colonialist oppression of millions of people, and was opposed to Catholic emancipation and the abolition of the slave trade, despite being forced to sign the Abolition Act in 1807. He was also a husband and father, whose human vulnerability can be felt even through the hastily composed messages exchanged between the men seeking to isolate and control him. In May 1801, as they walked together in the grounds of Kew Palace, George told one of his physicians, Thomas Willis (1754-1827), of the disturbed night he had had. In Willis’ view, George was trying to downplay the extent of his condition to his doctors and closest family. Willis noted that the king made ‘such remarks as betray a consciousness in him of his own situation, but which are obviously made for the purpose of concealing it from the Queen. He frequently called out, ‘I am now perfectly well, and my Queen, my Queen has saved me’’.

However, Willis declared that the King did not trust his wife, Queen Charlotte (1744-1818); George feared, with good reason, that anyone he confided in would report their conversation. That same month, Willis’ brother and fellow royal physician John Willis (1751-1835) wrote that ‘every means possible should be used’ to ‘control’ the King.

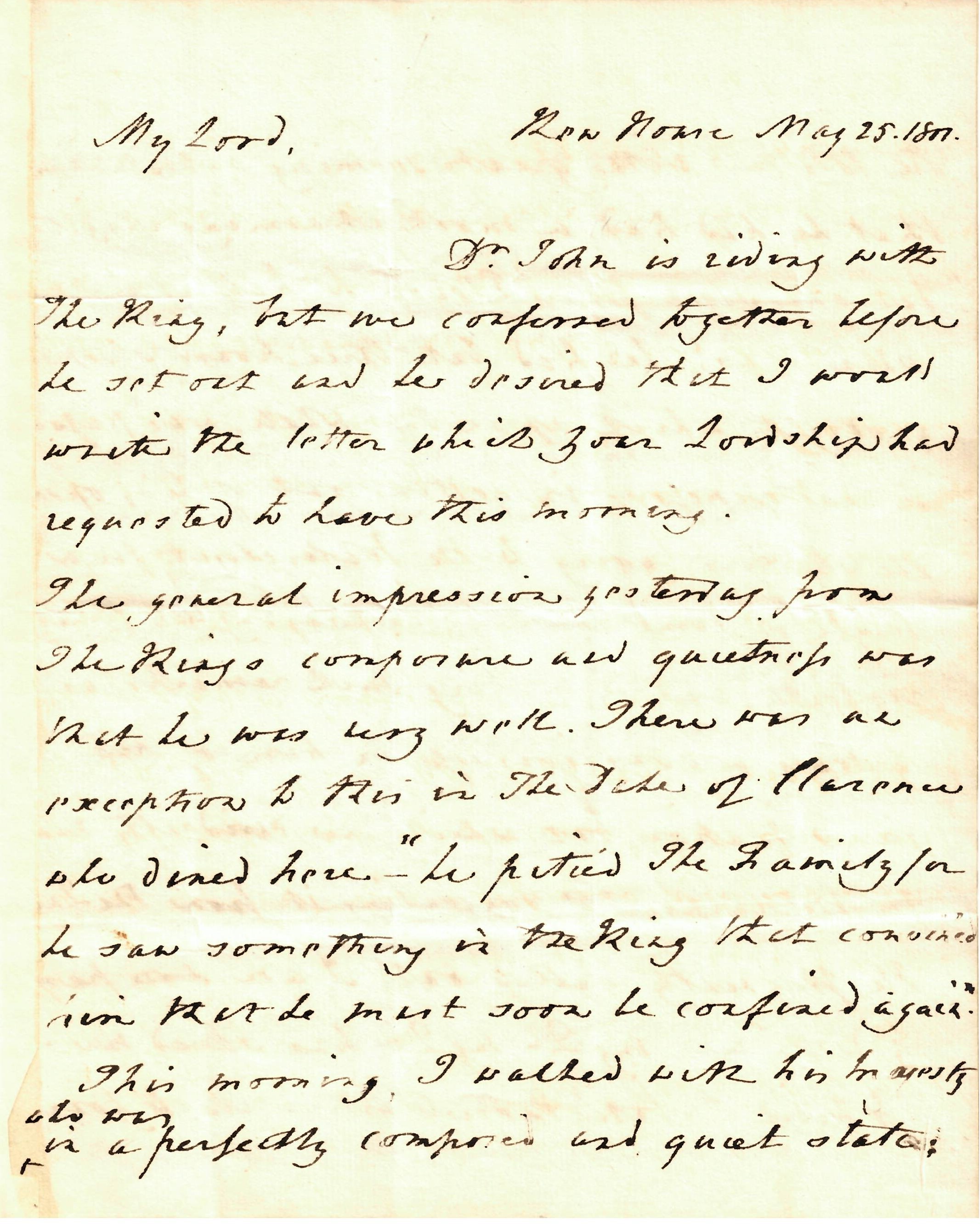

George particularly resented Thomas, John, and their third medical brother, Robert Willis (1760-1821). He was desperate to escape to the seaside resort of Weymouth, where he had spent many summers, but failing that, he just wanted to get away from his doctors. They, however, were determined not to let that happen. Thomas wrote ‘with respect to Windsor, [the King] should be prevailed upon that it would be the highest imprudence to go there without any of us, and yet he means to go there that he may get rid of us’. One of their methods of maintaining control over the King was to insist that John Scott use his influence to persuade George of the necessity of ongoing medical supervision. In almost all their letters to Scott in May 1801, the doctors put pressure on him to use his meetings with the King to convince the monarch to comply with their wishes. On 25 May, Thomas Willis wrote a letter to Scott, ‘It is too evident, my Lord, that it cannot be […] safe for the King to go to Weymouth so soon as he intends. Your Lordship will therefore, no doubt, think it requisite to take steps to prevent it as soon as possible’.

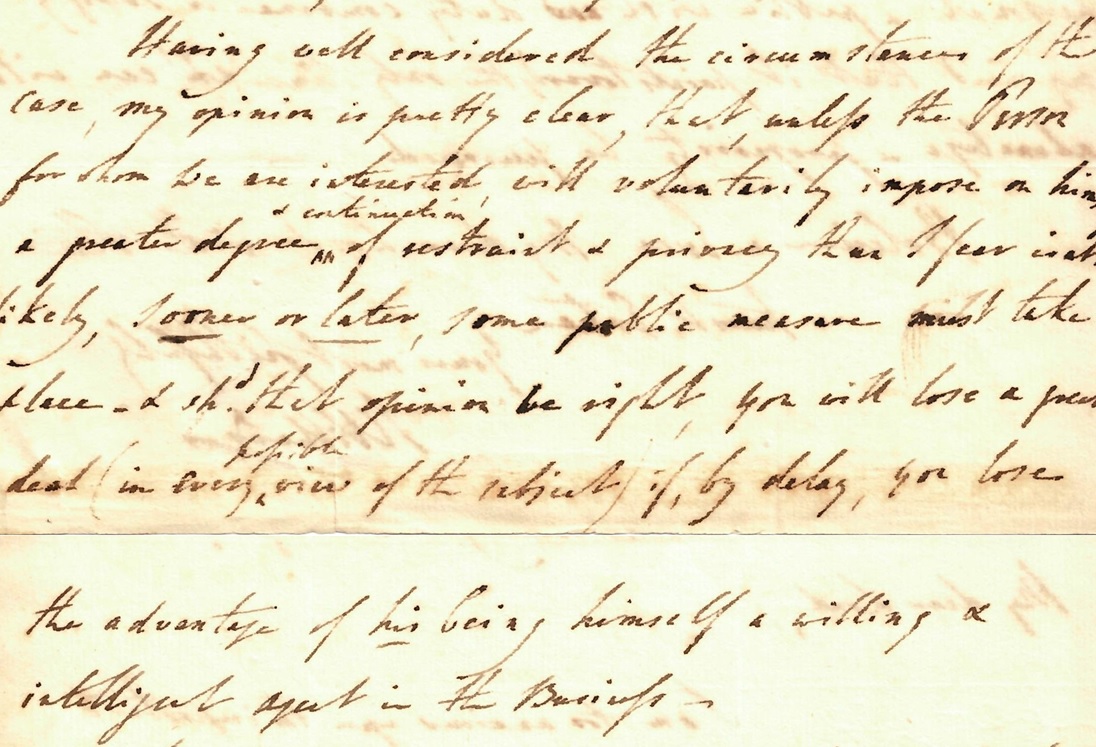

Given they felt the need to constantly prompt him, it seems that Scott was not initially eager to do the doctors’ bidding. It may have taken a fellow parliamentarian to convince Scott that acquiescing to the physicians was in his own career interests. On 26 May, John Villiers (Earl of Clarendon) (1757-1838) sent Scott a letter stuffed with euphemisms, that was nevertheless intended to convey a clear warning to its recipient: ‘my opinion is perfectly clear, that, unless the person for whom we are interested will voluntarily impose on himself a greater degree & continuation of restraint & privacy than I fear is at all likely, sooner or later, some public measure must take place - & should that opinion be right, you will lose a great deal (in every possible view of the subject) if, by delay, you lose the advantage of his being himself a willing & intelligent agent in the business’.

Villiers is saying that if the King does not submit to his physicians, they may declare him unfit to rule. Such a judgement could invalidate the King’s recent decisions, such as appointing Scott as Lord Chancellor. This would make it easier for the Prince of Wales, who would become Prince Regent, to strip Scott of his role and appoint an adviser of his own choosing. There was clearly a conflict of interest in that Scott, who was tasked with impartially reporting on George’s condition, benefited from the King continuing to be judged mentally capable. Whatever his motivations, Scott succeeded in convincing the King to delay his trip to Weymouth until the start of the parliamentary summer recess. This would enable his physicians to continue to monitor him at Kew during a crucial period, and Scott to become established as Lord Chancellor.

If George had to stay at Kew, however, he was determined to make one important change. On 5 June, Thomas Willis related the fate of his brothers: ‘[the King] has disposed both of Dr John’s and Dr Robert’s room – a clear proof he does not expect them. And it is to be suspected in this case that if either went, if deemed necessary, without some further communication with the King, this circumstance might prove more hurtful to his Majesty’s mind, as their attendance on the other hand might be supposed to do good’. Thomas Willis appears compelled to acknowledge that the presence of his brothers is potentially damaging to the King’s wellbeing. Thomas himself seems to have been kept at arm’s length at this point, relying for his updates on Dr Thomas Gisborne (d.1806), with whom George was more comfortable.

The letters cover two further periods of illness, the first in 1804, when there was again a protracted tussle over whether, when, and by what means George should be allowed to go to Weymouth. In 1811, the possibility of a seaside getaway is never even mentioned. This was to be the most consequential episode of illness, from which the King never fully recovered. George had experienced much tragedy in his life; two of his sons, Alfred (1780-1782) and Octavius (1779-1783), had died in childhood, and in November 1810 he lost his adult daughter Amelia (1783-1810). A report by the royal physicians on 13 November links the King’s relapse to his anguish over Amelia’s death. The princess’s relationship with her long-term boyfriend and equerry to the King, Charles FitzRoy (1762-1831) had for years been kept secret from George, as all concerned assumed he would not approve. The physician, Henry Halford (1766-1844), was present when George was informed of the contents of Amelia’s will, in which she left everything to Charles. This news came shortly after the King had been told his powers would finally be taken from him and given to Prince George, and Halford describes the King’s reaction to both events in the following stoical, but not completely unsympathetic, words: ‘His Majesty has felt forcibly all that [has] passed, but most reasonably, and without the least inconvenient excitement or agitation’. Halford wrote that ‘[the King] has said he will not touch a hair of FitzRoy’s head – but will not have him at Windsor in future.’ Almost 40 years previously, John Scott had himself had to elope with his fiancée Bessie Surtees (c.1750-1831) as her father had disapproved of him. One wonders whether, upon reading Halford’s note, Scott’s feelings were more of solidarity with Amelia and Charles, or sorrow for the King. Bessie Scott and her father were eventually reconciled, but George and Amelia would never have that chance.

In the 1801 and 1804 letters George is an energetic figure, who often succeeds in escaping his doctors and advisers for a day to go horse-riding or visit friends. But by 1811 he was mostly blind and living with rheumatism, and spent most of his time in his rooms. The brutal treatments he continued to be subjected to on account of his mania would not have helped with the mental pain he was clearly experiencing. He was, however, able to find pleasure in playing the harpsichord and occasional peaceful conversations with family and friends. During this time he often spoke of, and with, loved ones who had died. His physicians wrote on 11 September that George, apparently believing the son he had lost 28 years before were still alive, ‘mentioned his resolution to make Prince Octavius Prince of Wales’. The final letter in the collection suggests that while George had once been able to physically give his doctors the slip, he was now able only to escape from them in his mind: ‘This morning at the interview with the physicians, His Majesty was in good humour and in high spirits, but so occupied with his own wild fancies that he seemed very soon to lose the impression of the physicians being still in the room.’

Felix Lancashire, assistant archivist

References

Several of the letters in this collection are published in Twiss, Horace (1844), The public and private life of Lord Chancellor Eldon, with selections from his correspondence.

Sources

- Lord Eldon. Letter to Dr. Monro asking him to attend Consultation of His Majesty's Physicians at Sir Henry Halford's, MS3011/51

- John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, Lord Chancellor. Autograph letter to Dr. Thomas Monro, MS3011/50

- Thomas Monro. Autograph letter to Lord Chancellor (Lord Eldon), MS3011/49

- Letter from Thomas Willis, MS6116/6

- Letter from John Willis, MS6116/4

- Letter from Thomas Willis, MS6116/2

- Letter from John Villiers, 3rd Earl of Clarendon, MS6116/7

- Letter from Thomas Willis, MS6116/8

- A report by the royal physicians to John Scott, MS6118/1

- Letter from Henry Halford, MS6118/2

- Copy of report to the Queen’s Council from the King’s physicians, MS6118/11

- Copies of reports to the Queen’s Council from the King’s physicians, MS6118/18