Under the skin: mapping the body

Under the skin: mapping the body

Anatomical illustrations are often abstract and conceptual, rather than artistic or life-like.

In order to simplify the human body for teaching, or to focus on particular organs or systems, other details you would see in the dissecting room have been removed or obscured.

Understanding how the individual parts of the body interact and function as part of the whole is vital to building an accurate picture of human anatomy.

Diagrams and schematic plans are an effective way of expressing the three-dimensional relationships between different body parts, without the distraction of detailed drawings.

In this way, illustrators have been able to map the human body, using idealised representations to communicate specific messages.

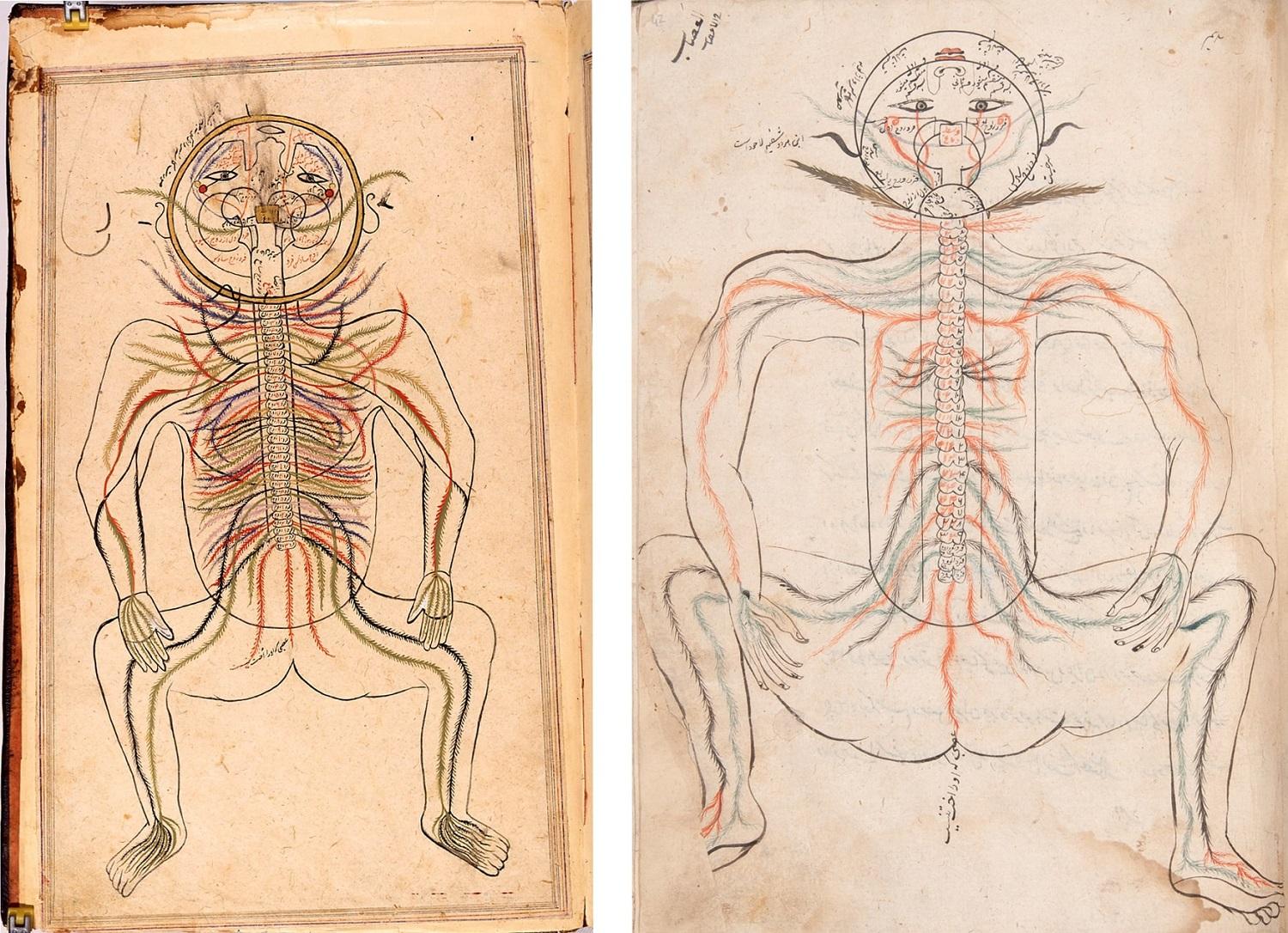

The nervous system

The nervous system in Tashrih i Mansur (Mansur's Anatomy)

RIGHT: Manṣūr ibn Ilyās, Persia [Iran], copied 1656.

LEFT: Manṣūr ibn Ilyās, Persia [Iran], copied in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Feathered lines are used here to indicate the wide reach of the nerve fibres, without the painstaking work of depicting each nerve. Colours are used to indicate the different branches and routes of the fibres. The arrangement of the facial features shows that this schematic diagram is a view from the back of the body.

Manṣūr’s anatomy is the first book from the Islamic world known to include anatomical illustrations of the whole body. It was first written around the year 1400, and the stylised illustrations were copied alongside the text throughout the following centuries.

Explore the complete manuscripts online: 1656 copy, 17th-18th century copy

View the catalogue records: 1656 copy, 17th-18th century copy

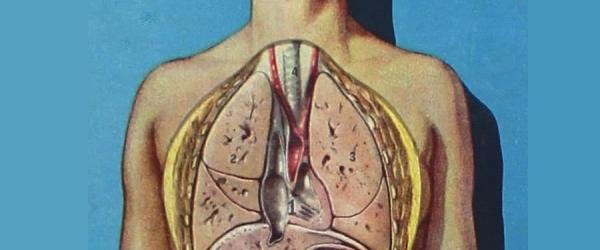

Japanese Scroll

LEFT: Internal organs and acupuncture points on the arms, in Shishi bessho zui (Illustrations showing how to perceive those who are to die and identify those who are to live). Hozumi Koremasa, Japan, 1820s.

The internal organs are vividly displayed here, alongside a schematic representation of acupuncture points relating to specific locations or systems inside the body.

The images in this manuscript combine traditional Japanese representations of the body with a different style depicting the internal organs adapted from western European models.

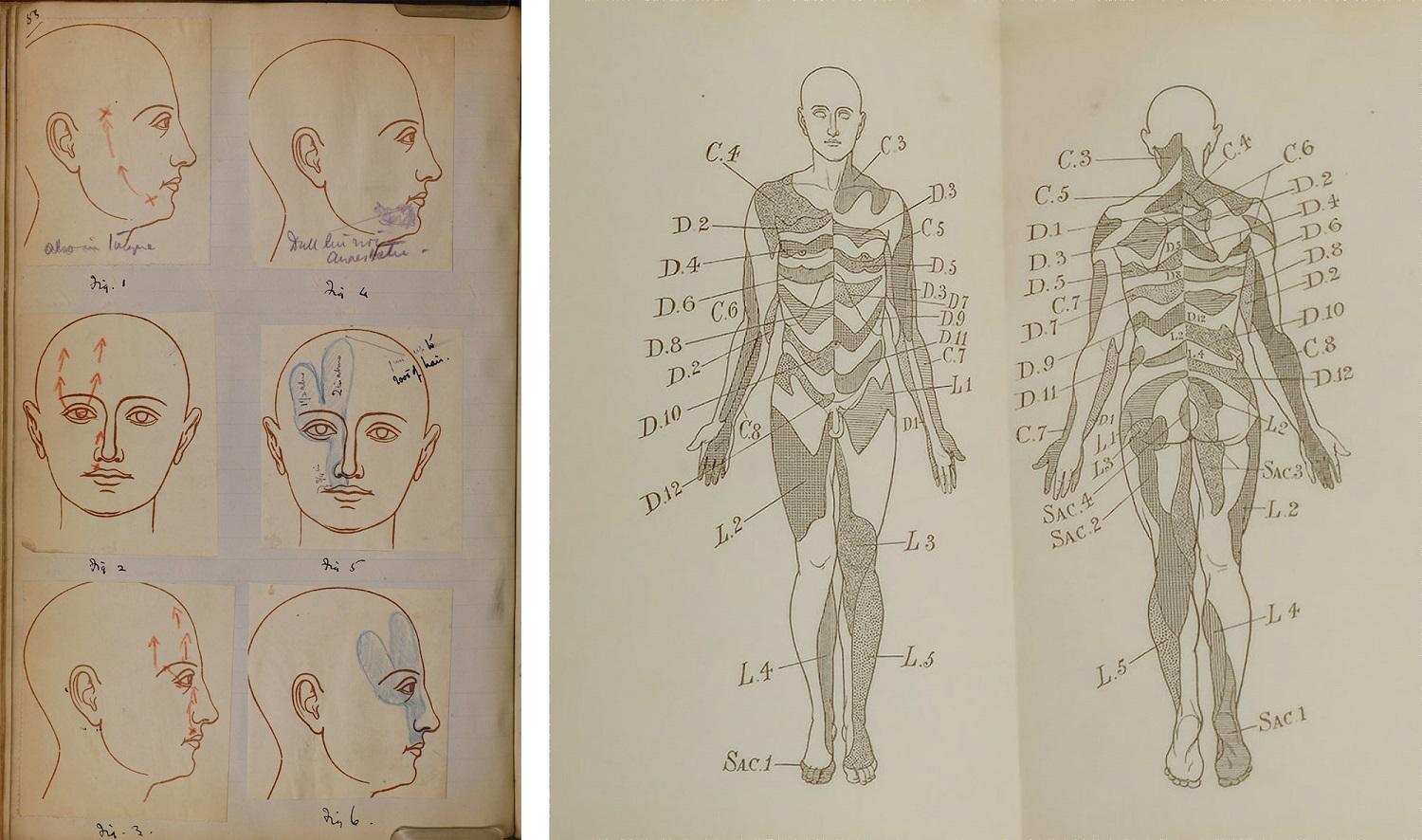

Mapping pain and pathology

LEFT: Regions of pain and numbness on the human face in case-records, chiefly from the London Hospital. Henry Head, 1890s.

RIGHT: Localisation of eruptions of herpes zoster across the body in The pathology of herpes zoster. Henry Head, published London, 1900.

Neurologist Henry Head studied how people felt pain and numbness on their skin. He had a particular interest in symptoms of the herpes zoster virus, which causes shingles. He took detailed notes of individual cases using pre-printed outlines of the body.

By recording patterns of disease on the external body, Head was able to understand and map the underlying anatomy within. He published diagrams showing which regions of skin connect to different sensory nerve fibres emerging from the spine.

Explore Henry Head’s casebook online

View the catalogue records for the casebook and the published study

Head 10 and the digestive system

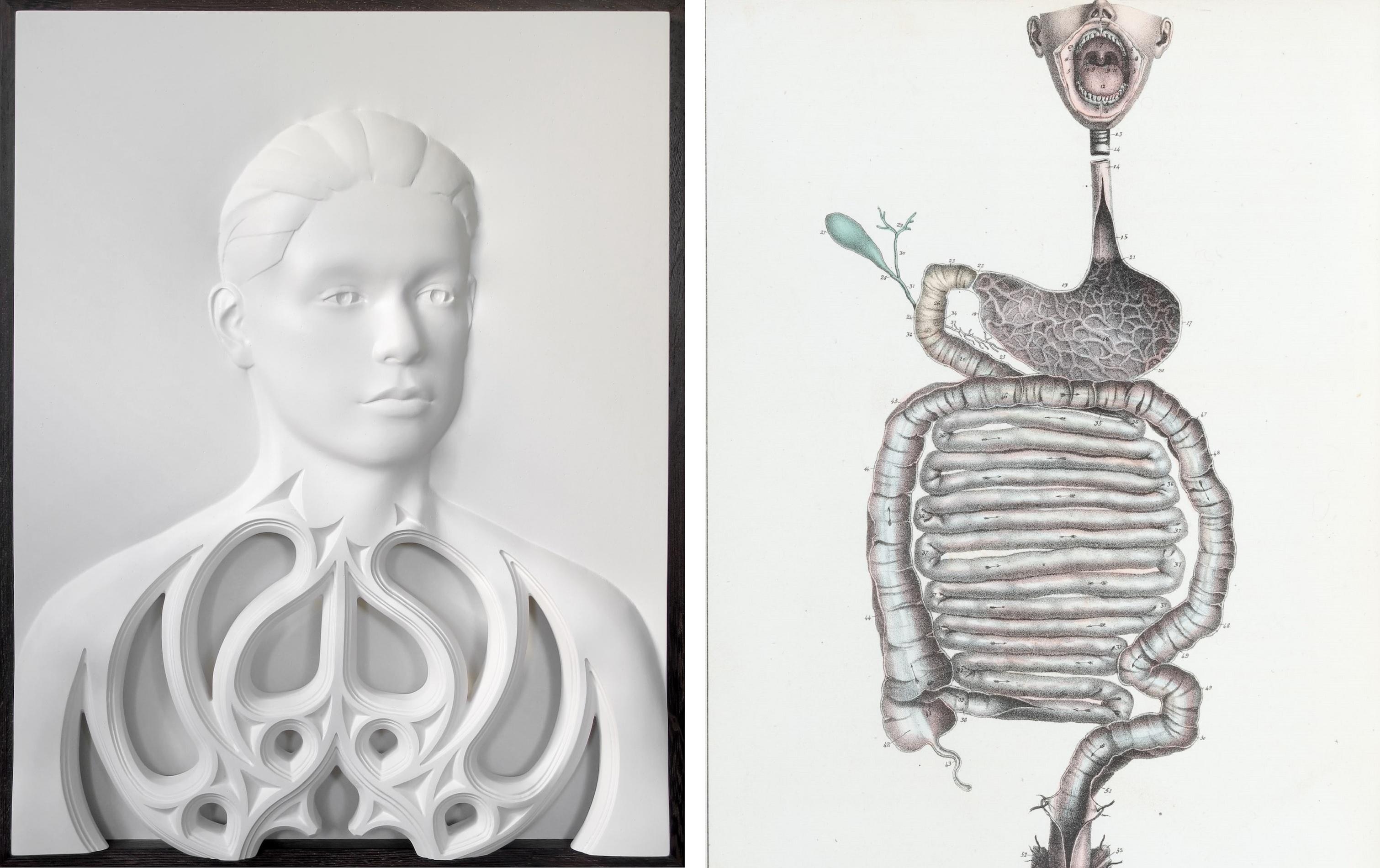

Left: Head 10. Bee Flowers, plaster, 2018.

This piece presents the body as an unchanging and highly ordered structure. The decoration echoes the design of gothic church architecture, reflecting Flowers’ interest in the lingering power of ideas and belief systems.

The smooth surfaces and regularity of form express the tension between the need for order and uniformity to make the body comprehensible, and the resulting loss of individuality.

Right: The digestive system, in Manuel d'anatomie descriptive du corps humain. Dissected by Jules Cloquet, drawn by Haincelin, lithograph prepared by De Frey, published Paris, 1825.

The alimentary canal runs right through the body. It is the only system shown in this striking composition, which maps the route of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus, via the oesophagus, stomach, and the small and large intestines.

The mouth is wide open, showing the soft palate, tongue, tonsils and other structures involved in eating and swallowing. Although the rest of the face is not shown, the composition gives the effect of a screaming person, as if the body is objecting to its treatment.

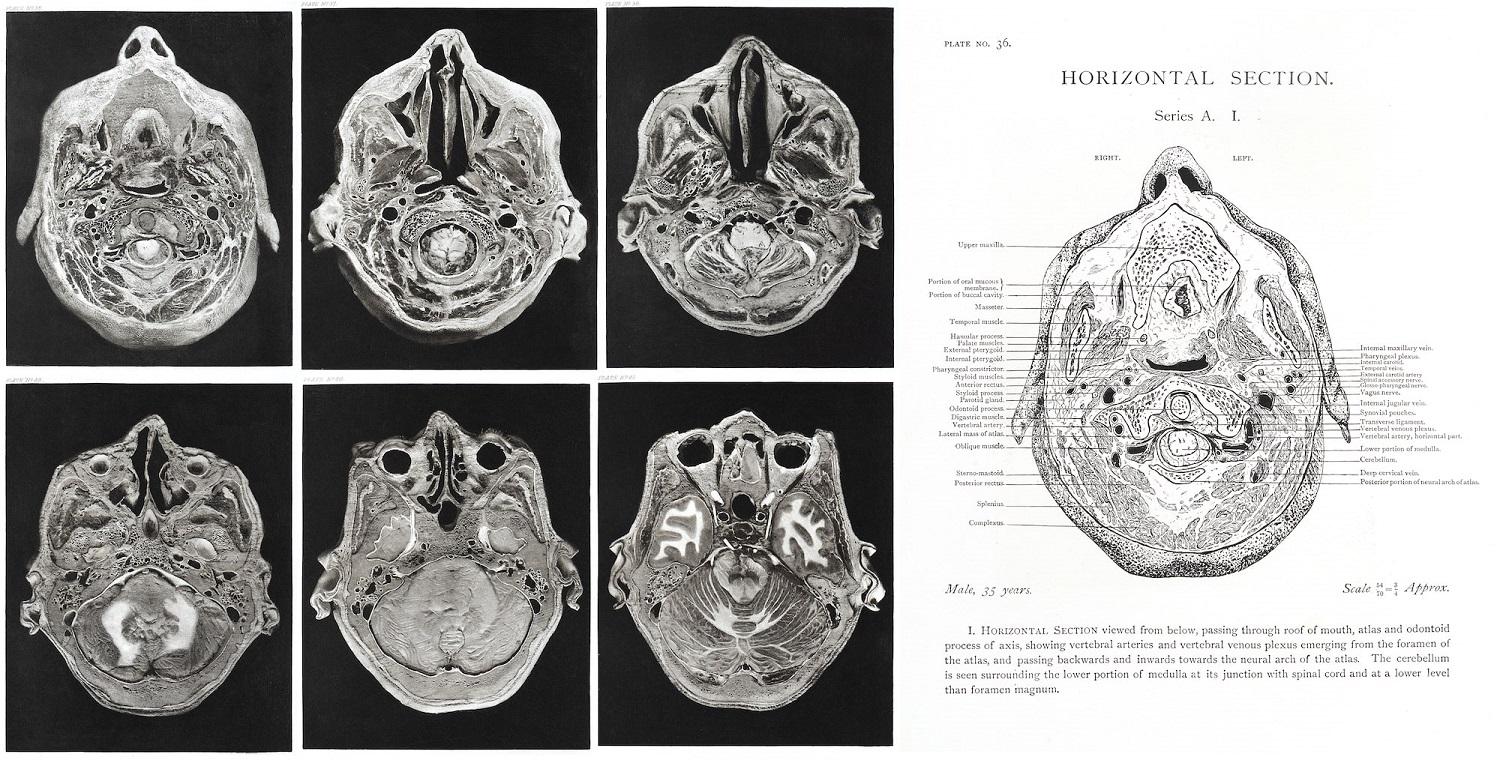

Horizontal sections of the head

Horizontal sections of the head of a 35-year-old male, in Atlas of head sections. Dissection by Sir William MacEwen, drawing by Flora MacEachran, photogravure by Messrs Annan of Glasgow, published Glasgow, 1893.

Surgeon William MacEwen prepared slices of frozen human brains made sequentially across the head at different angles. Frozen slices were used to preserve the shape of the brain, which otherwise ‘sinks by its own weight and becomes distorted’ when removed from the skull.

Fifty-three of MacEwen’s samples were photographed and reproduced using the photogravure technique, in which a photographic image is reproduced using a copper plate. The effect produces extremely rich dark tone and high contrast with the lighter areas.

MacEwen edited the photographs to outline areas such as the borders between different tissue types. Flora MacEachran, about whom we know very little, made a line-drawn key to show the different features in each photograph.

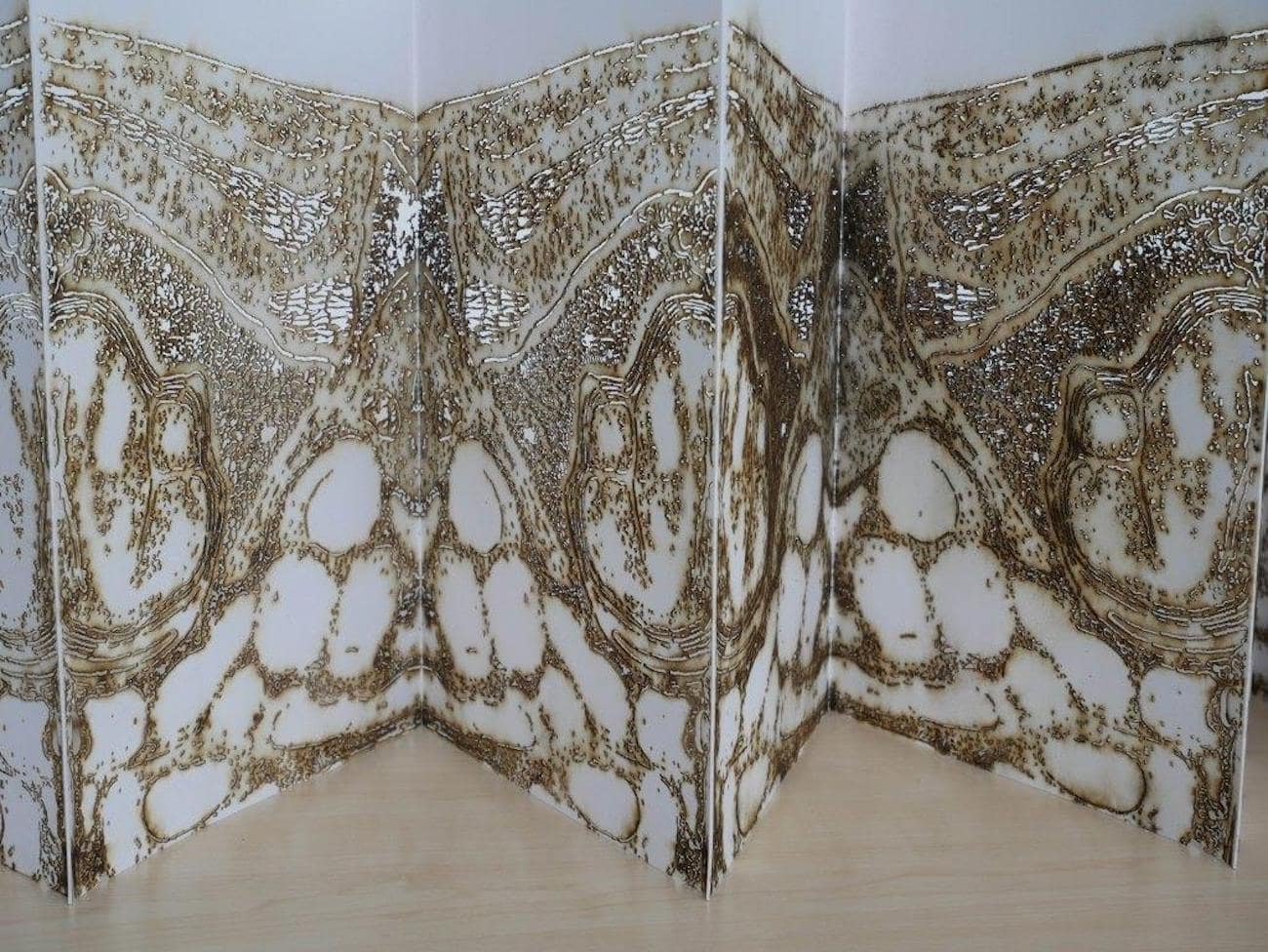

LEFT: UnFolding Sheets. Towards A View of One’s Head. Andrew Carnie, laser-cut paper, 2019.

The pages of this folding book have been laser cut with an image of the human brain, which grows fainter as the book progresses. It reinterprets the three-dimensional structure of the brain, in which the gaps are as important as the brain matter. It is based on images from William MacEwen’s Atlas of head sections (below).

LEFT: Boundaries and the Body with Andrew Carnie

Andrew Carnie discusses his artwork exploring his interest in boundaries and the body, including his artwork 'UnFolding Sheets'.

Andrew Carnie is an artist and researcher who has worked with scientists as part of his practice for twenty years. His work explores how we as humans take on the information and ideas thrown at us from science. His work asks how we make sense of our selves in this changing world of scientific discovery and the imagery of science and how we incorporate science into our sense of self.

This is a recording of the Digital Museum Late held on Thursday 5 November.

Part of the exhibition 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity'. Explore further: