Under the skin: being the body

Under the skin: being the body

Some of the bodies illustrated in this exhibition are of individual, identifiable people. Other images are generalised or idealised, based on multiple bodies.

Bodies were obtained legally and illegally from the gallows or from workhouses, but were also taken unlawfully from hospitals, poor houses and graveyards. In most cases, people did not give their consent to be posthumously dissected and represented in this way.

How the anatomist or artist depicts a body greatly influences how we react to their illustration, and how we feel about the person represented. Clinical drawings can appear detached and impersonal, concealing both the dissection process and the once-living subject. Others emphasise the visceral details of the body, sometimes making it appear alive again, provoking feelings of disgust, pity and curiosity.

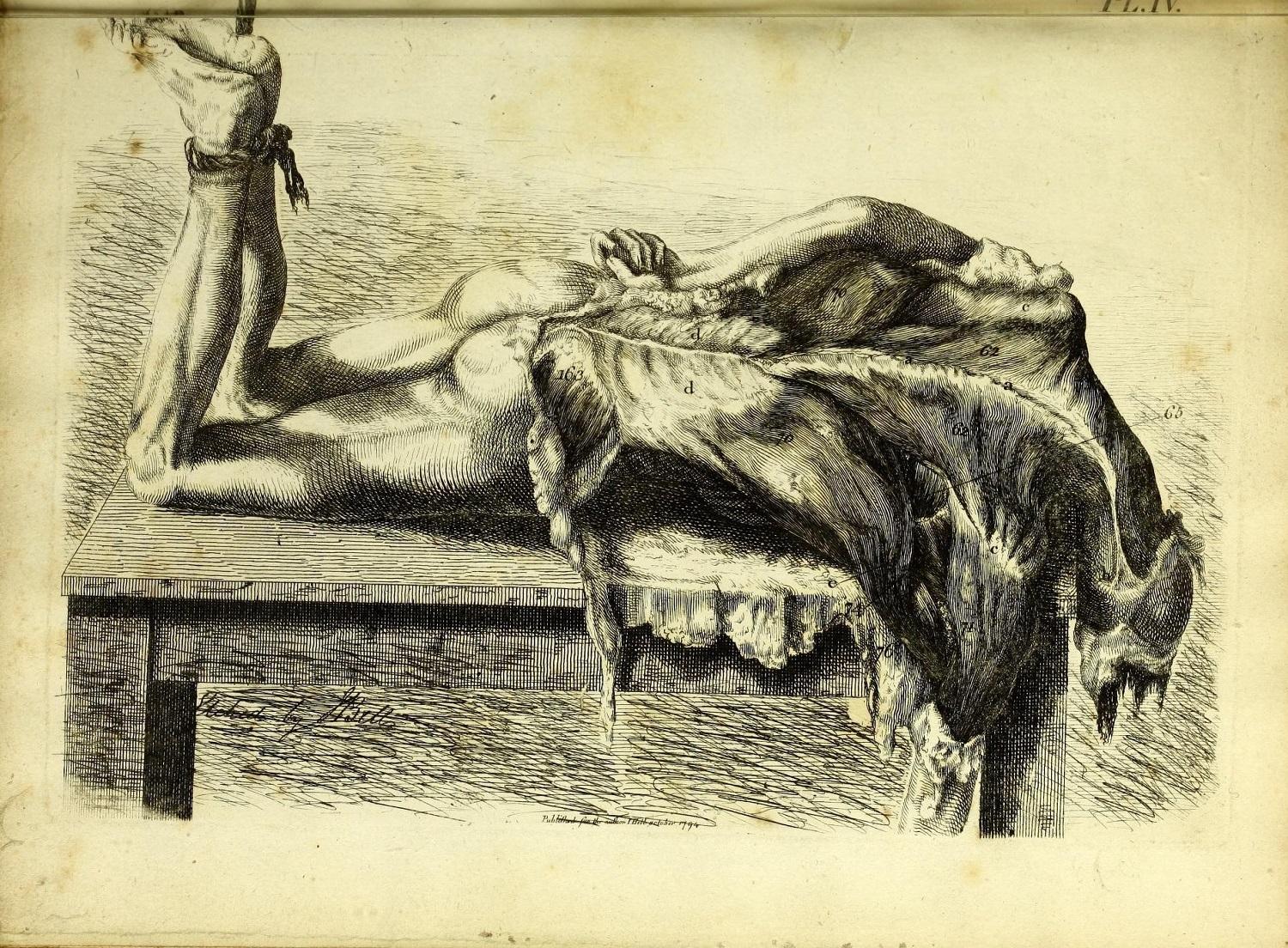

Bell's etching of the muscles

The muscles of the back, showing the trapezius, latissimus dorsi and deltoid muscles, in Engravings explaining the anatomy of the bones, muscles and joints. Dissection, drawing and etching by John Bell, published Edinburgh, 1794.

John Bell criticised the works of other anatomical illustrators for being ‘artistic’ and contrived. In contrast, Bell’s plates were intended to show students the realities of the body and the dissecting room.

The resulting drawings show sometimes gothic and gruesome scenes. In this picture, the flesh of the body appears to drip towards the floor, and the bound feet suggest execution or torture.

The use of etching allowed Bell to use loosely controlled, flowing lines, which create a feeling of unsettling movement. The image is very dark, and the details of the muscles – the subject of the picture – are not visible.

View the catalogue record for Engravings explaining the anatomy of the bones, muscles and joints or Explore the complete book online

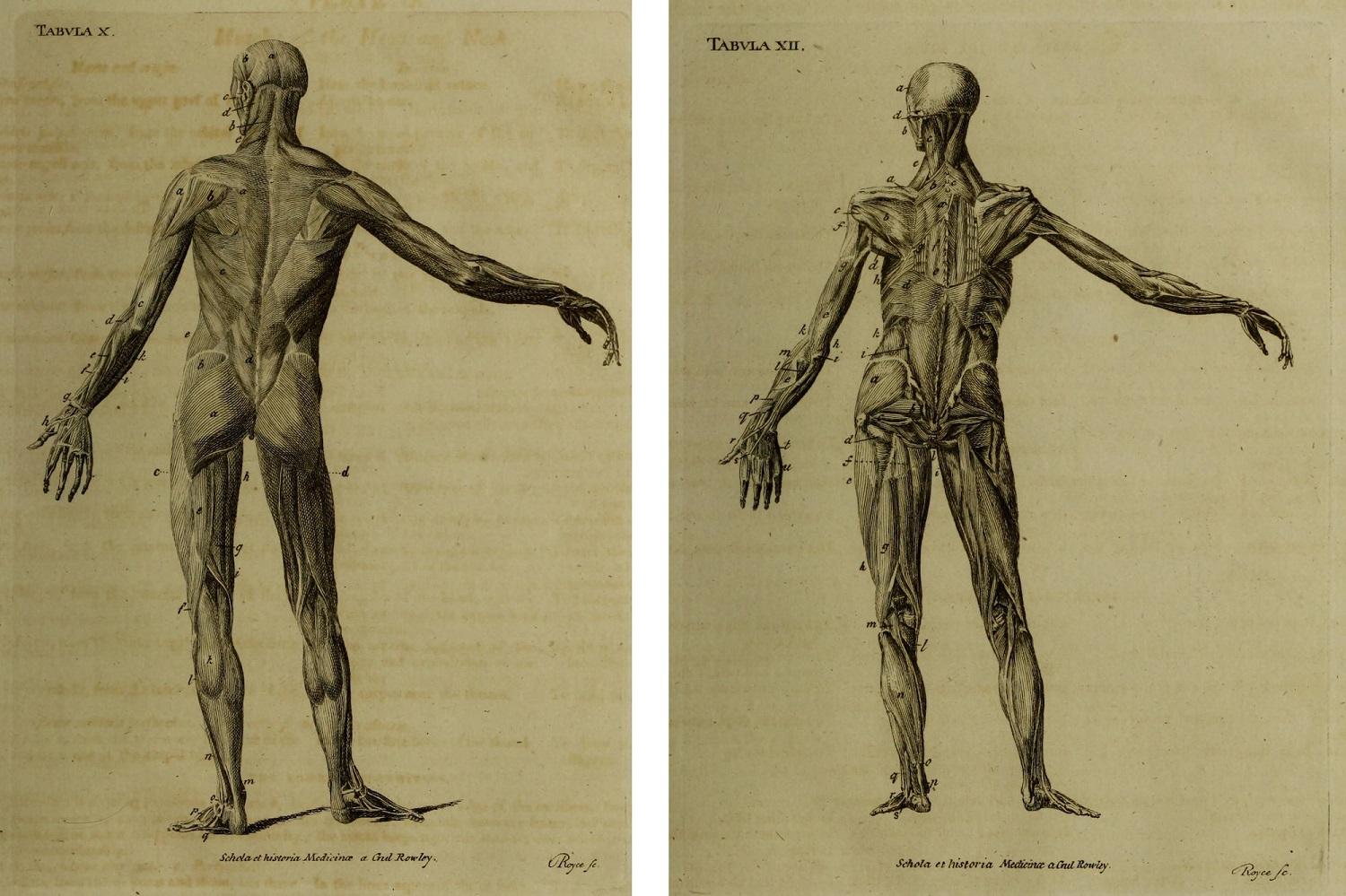

Rowley's illustrations of the muscles

First and second layers of muscles of the back of the body, in Schola medicinae, or The new universal history and school of medicine. Text by William Rowley, drawings copied from earlier models, engraving by John Royce, published London, 1803.

These dissected bodies stand isolated in space. They are intended to instruct the viewer, without any distracting context or background. With their pared back appearances, the images are far removed from any living person or people who were dissected.

Copperplate engraving enables artists to illustrate fine details. Here, the shape, texture and direction of the muscles are suggested by curved parallel lines which create a subtle shading effect.

View the catalogue record for Schola medicinae or Explore the complete book online:

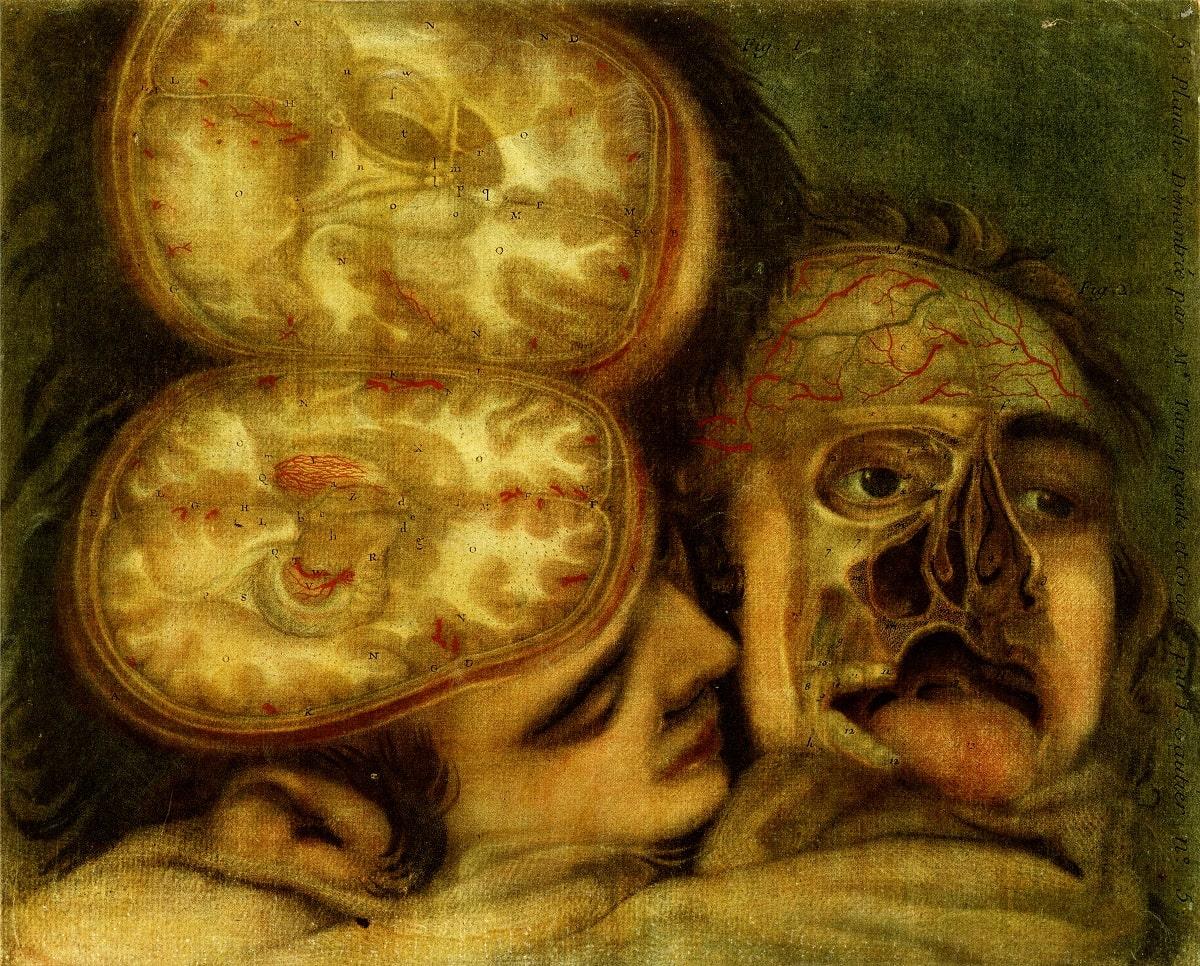

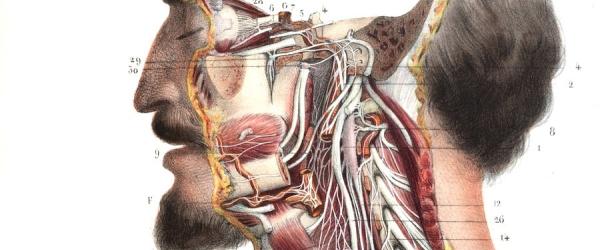

Two views of the anatomy of the head

Two views of the anatomy of the head, in Anatomie de la tete. Dissection by Pierre Train, drawing and engraving by Jacques Gautier d'Agoty, published Paris, 1748.

The intimacy of this composition is shocking. Two heads are drawn as if still living, lying closely together in a bed. Gautier d’Agoty’s anatomical images often use disconcerting poses like this subverted portrait. They can seem disrespectful to the dissected bodies. Gautier d’Agoty said that his aim was ‘to make the image of death agreeable’.

Highly saturated colours increase the unsettling effect of this portrait. Gautier d’Agoty was one of the first engravers to print medical images in colour. He used a mezzotint technique, in which four copperplates are treated using red, yellow, blue and black to give a rich, textured printing tone.

Mezzotint images tend to be dark and without fine detail – the difficult and time-consuming process was not adopted routinely by other printers of medical books.

View the catalogue record for Anatomie de la tete or Explore the complete book online

John Turner speaks about his early perception of anatomy as ‘very inhumane’

John Turner (b.1942) grew up in Sheffield and studied medicine in London.

'I mean I didn’t like anatomy, I knew I wasn’t going to be a surgeon. When I did my biology A Level back at Worksop College we had to do a practical where you had an external examiner and we had to dissect these appalling dog fish yeah, which were preserved in formaldehyde. So you had your little dissection kit which was like a medical kit of little scalpels and had dissecting forceps and the external examiner came over and looked at my offering of the dog fish and said, "Did you use an axe?" So I thought surgery is definitely not for me from an early stage. I think anatomy I saw as very, very inhumane subject from quite early on. I remember we had our very first introduction to this where we were in sort of traditional lecture theatre and we were being taught about what the anatomy course would consist of and one of the anatomy lecturers took out a human limb, severed human limb took it out of its wrapping and threw it into the assembled students, newly arrived students for somebody to catch. He said, "This is the sort of thing you’ll be working on." I didn’t think much of that.'

The full interview with John Turner can be found on the library catalogue

Explore more oral history recordings about anatomy and imaging

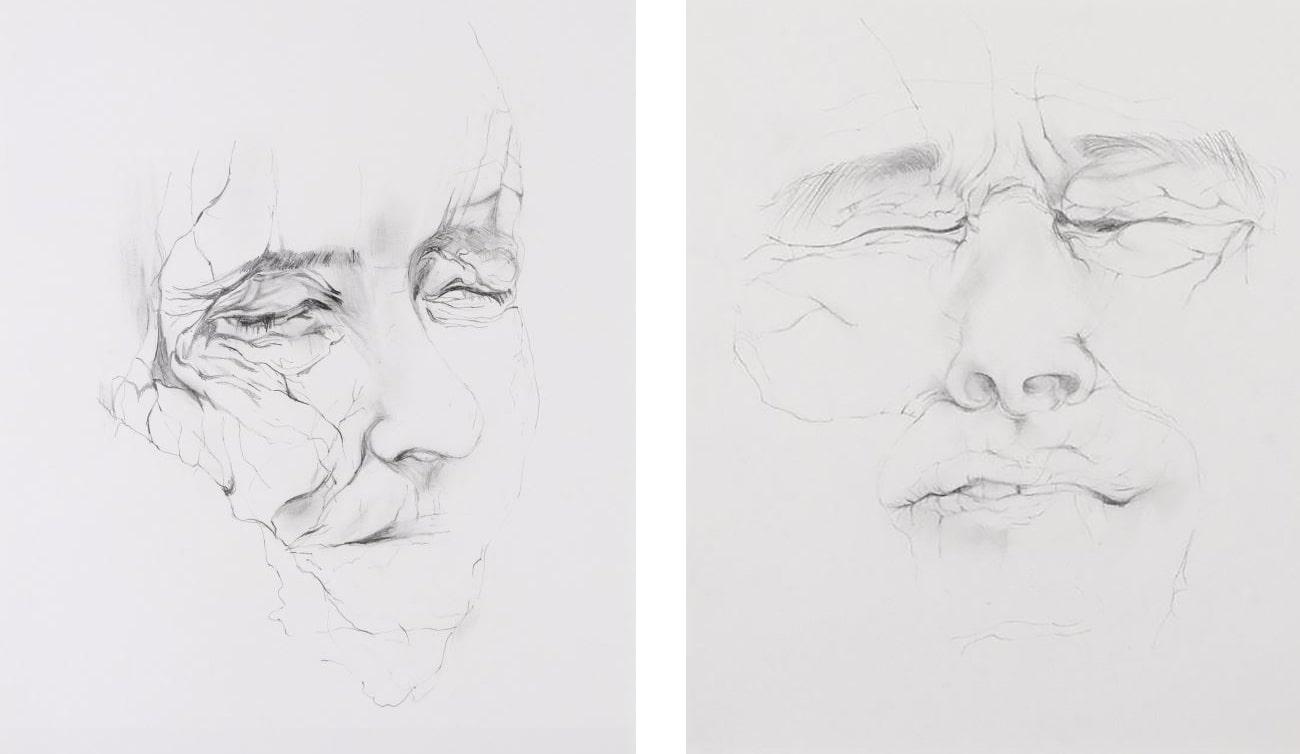

Cadaver by Angela Palmer

Cadaver. Angela Palmer, pencil on paper, 2005.

Angela Palmer made these drawings of cadavers at Oxford University's Department of Human Anatomy, during her time as a student at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. The bodies were donated to medical science.

These faces have been thoughtfully and sympathetically reproduced – but they are very uncomfortable to look at. They appear to be in pain, and they are peculiarly personal and emotionally invasive – perhaps more so than if the internal anatomy was on display.

Part of the exhibition 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity'. Explore further: