Representations of the Royal college of physicians in medical satire

Representations of the RCP in medical satire

Speak, goddess! Since ’tis thou that best canst tell,

How ancient leagues to modern discord fell;

And why physicians were so cautious grown

Of others’ lives, and lavish of their own […]

There stands a dome,† majestic to the fight,

And sumptuous arches bear its oval height;

A golden globe, plac’d high with artful skill,

Seems, to the distant sight, a gilded pill

†The College of Physicians

Samuel Garth, ‘The dispensary’, 1699

As a royal institution representing doctors, many of whom were well known figures in society, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and its members have been in the public eye for over 500 years. Consequently, the RCP has been the repeated target of satirical commentary.

Satirical artists have represented diverse aspects of the RCP’s work and its members. The artist William Hogarth (1697–1764) commented upon the cruelty of dissection as a lawful punishment while also playing on common – and comical – stereotypes of doctors, such as depicting them wearing a wig and sniffing a cane. Other artists focused on internal squabbling, controversial medical developments, and the stereotyped reputation doctors had for ignorance and pretension.

The RCP was established in part to protect the public from the harmful work of quack doctors. However, the RCP and the medical profession were attacked as quackery in disguise, and were accused of the same offences as the unqualified practitioners they sought to protect the public against.

The College suspended

The College suspended

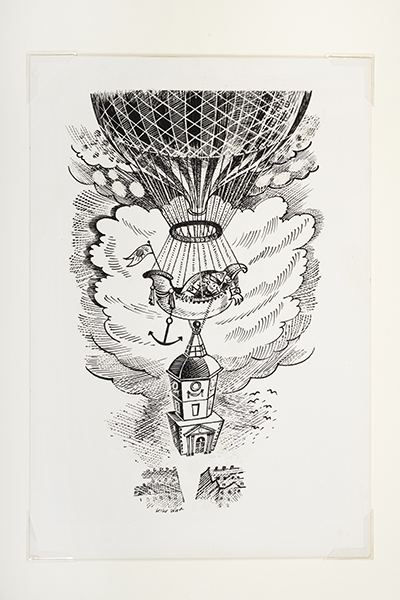

Drawing on scraperboard by Leslie Wood, 1988

2009.2

In this light-hearted illustration, the artist ridicules the ineffectiveness of the RCP and its members. Suspended from a hot air balloon, piloted by the fictional 18th-century German nobleman Baron Munchausen, is the RCP’s Cutlerian anatomy theatre.

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen tells the tale of the Baron’s impossible and outlandish exploits. His adventures were illustrated by Leslie Wood for a 1948 Cressett Press edition, but this illustration was a later commission and was not included in the 1948 publication. The Baron’s damning of the RCP is, however, part of the original story. He cheerfully recalls lifting the RCP building from the earth, by balloon, during their annual dinner:

‘Though this was meant as an innocent frolic, it was productive of much mischief to several respectable characters amongst the clergy, undertakers, sextons, and gravediggers: they were it must be acknowledged, sufferers; for it is a well-known fact that during the three months the college was suspended in the air, and [the members] therefore incapable of attending their patients, no deaths happened.’

The Baron probably had bitter experiences of being a patient, because he implies that the health of London greatly improved during the time that the doctors were unable to treat their patients. This modern illustration shows a fun, more carefree subject for medical satire – a contrast to many of the earlier images in this exhibition. It was published in the Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1997, accompanying an article on ‘The College suspended’.

The siege of Warwick-Castle or the battle between the fellows and licentiates

The siege of Warwick-Castle or the battle between the fellows and licentiates

Engraving by unknown artist, 1768

PR15116

The RCP’s most embarrassing historic episode, the ‘Siege of Warwick Lane’, is ridiculed in this print.

On two occasions in 1768 a small group of RCP members broke into the RCP’s premises, then at Warwick Lane near St Paul’s Cathedral. They invaded the Committee Room and disrupted the elections of officers.

This ‘Siege’ was essentially a battle between RCP fellows and licentiates, following decades of antagonism. Only doctors who were educated at Oxford or Cambridge universities could become fellows, while doctors educated elsewhere could become a licentiate, a lower form of membership. Despite being charged higher fees than the fellows, licentiates were barred from participating fully in RCP business and from voting in elections.

The print satirises both factions in the dispute: the Scottish doctors (the licentiates) are depicted as brutish, with their leader wearing a jester’s hat, and the fellows are shown as quacks and their leader (probably the RCP’s president) as the skeleton Death. The licentiates forcing medication on the fellows can be interpreted as the RCP getting a taste of its own medicine, or the licentiates curing the RCP of its ills.

The ridicule directed at everyone involved after this event persuaded the licentiates to change tactics and protest through the law courts instead, and the fellows eventually made a series of concessions. The dispute about who could be a member of the RCP and under what criteria was not fully settled until the Medical Act of 1858.

Doctors differ

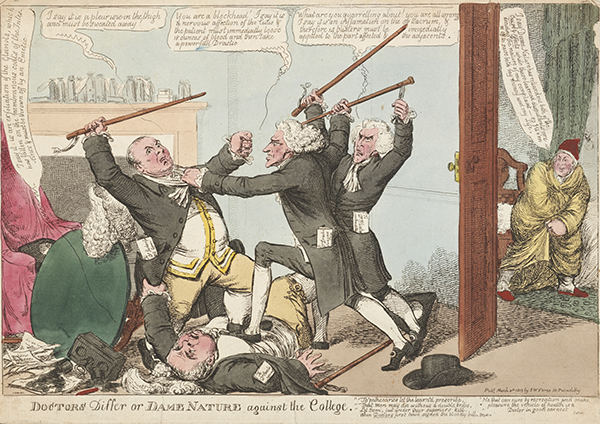

Doctors differ or dame nature against the college

Coloured etching by Charles Williams, published by Samuel William Fores, London, 1813

PR15011

Four elderly doctors fight over a patient’s diagnosis and treatment. They have arrived at the patient’s home with their prescriptions predetermined – whoever’s treatment is used will profit. The doctors are identified as synonymous with their treatments, which can be seen written on documents protruding from their pockets.

‘Dr Emetic’ insists that the patient suffers from ‘exfoliation of the Glands’ and must be purged; ‘Dr Sudorific’ argues for ‘a pleurisie in the thigh’ which must be ‘sweated away’; ‘Dr Drastic’ claims that ‘it is a nervous affection of the cutis and the patient must immediately loose 18 ounces of blood’, while ‘Dr Blister’ declares that ‘it is an inflamation on the os sacrum’ to be cured by the application of ‘14 blisters’. Through the open door the patient has used the commode and declares ‘I say Dame Nature has relieved me both of the Cause & Effects while these learned disputants are deciding the nature of my complaint—so I'll be off to save both my money and my Life.’

Doctors – and through them the RCP – are presented here as petulant and incompetent, their involvement acting against nature. The patient’s exclamation of saving ‘both my money and my Life’ reiterates the common satirical themes that doctors were focused on making money, and that a visit from the doctor could result in death.

Charles Williams, as chief caricaturist for the leading British publisher S W Fores, has used a popular satirical punchline in his critique of doctors and the RCP: ‘doctors differ’ while their patients suffer – or in this case manage to heal themselves.

View catalogue entry for Doctors differ or dame nature against the college

Part of the exhibition A taste of one's own medicine. Explore further: