Related pages

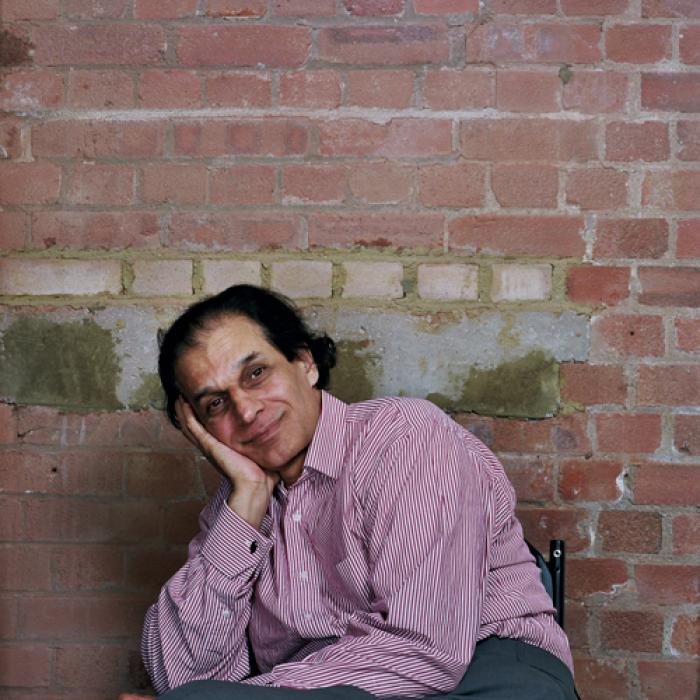

‘I ain’t broke, you don’t need to fix me’ – Jamie Beddard

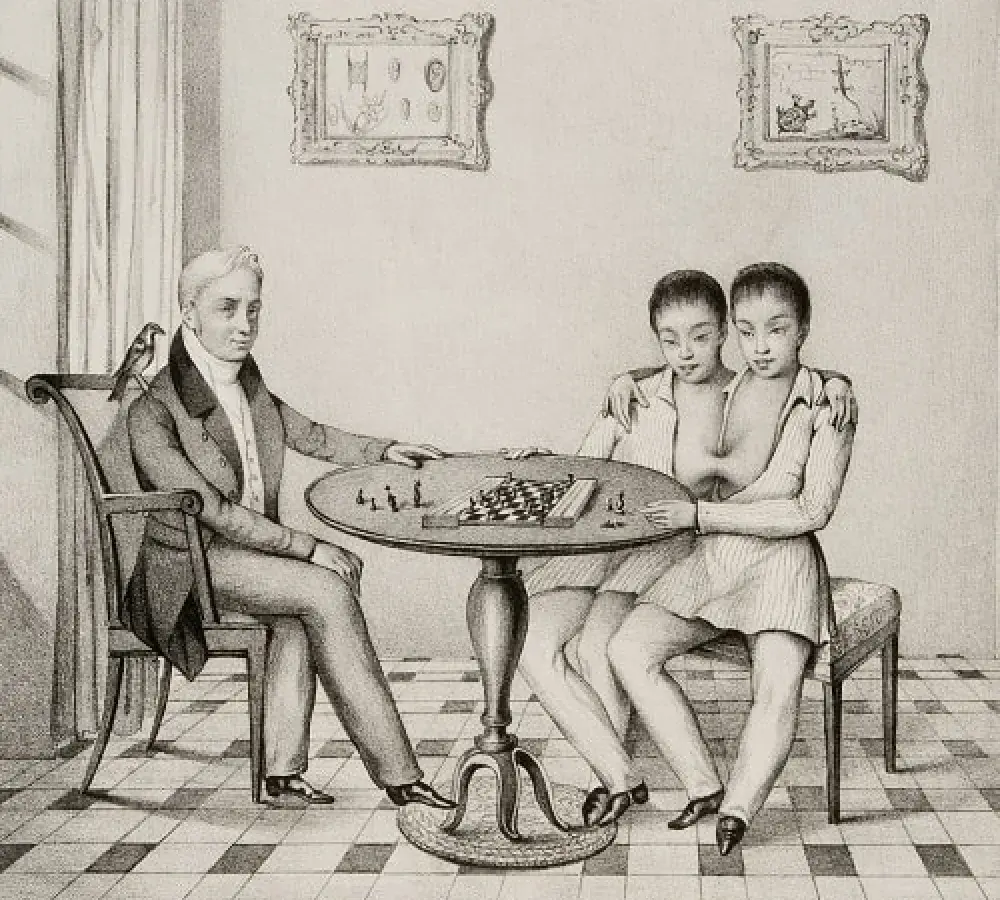

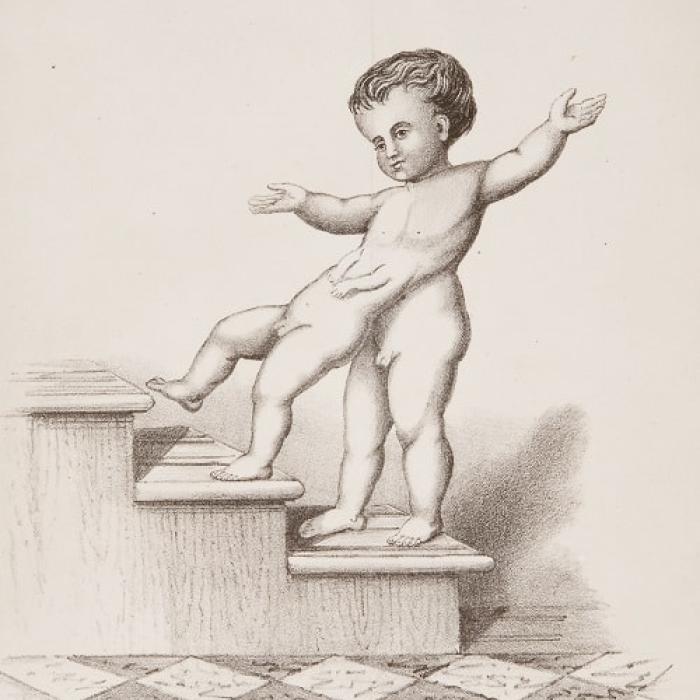

How do we interpret the past – and how far can we make judgements on historic representations using today’s sensibilities? A group of rare portrait prints of disabled people from the 17th to the 19th centuries formed the basis of the RCP’s Re-framing disability exhibition in 2011.

Cabinet of curiosities

Cabinet of Curiosities: how disability was kept in a box was an entertaining, challenging and inspiring event held at the RCP last Monday evening, 20 January.

‘Re-framing disability': portraits from the RCP displayed in Parliament

‘Re-framing disability': portraits from the RCP. Displayed in Parliament from the 2 December 2013

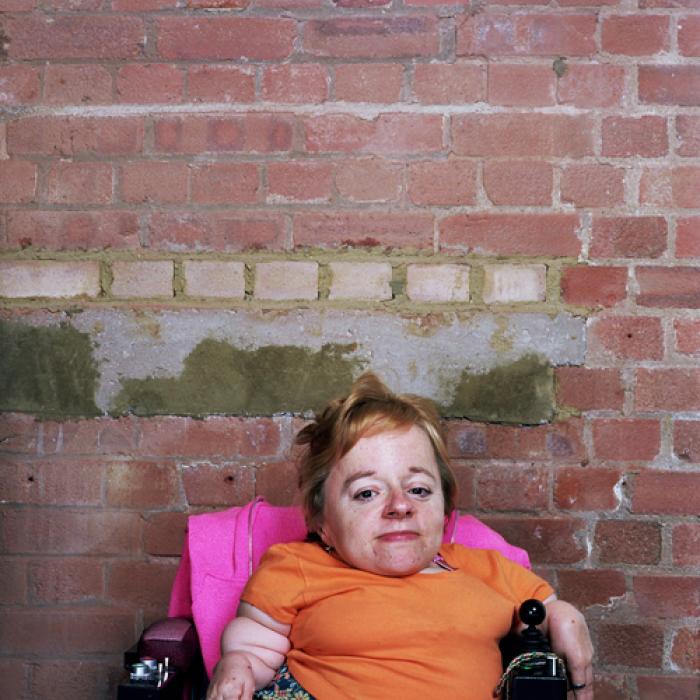

‘If we’re going to get looked at anyway, we might as well get paid for it’

These are the words of Sophie Partridge, a disabled focus group participant discussing the representation of disabled people, as part of a new exhibition at the Royal College of Physicians (RCP).

RCP and Shape win prestigious award for ‘inspired’ exhibition

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and partners, Shape, have won a top award for helping to build a more inclusive world for disabled people, with their ‘challenging’ exhibition of RCP portraits Re-framing disability: portraits from the Royal College of Physicians.