More information

Related pages

The merchant, his wife and her parrot

A merchant has to go on a long journey, leaving his wife behind at home. He gives her a parrot placed under a magic spell to keep her company while he is away.

Pamela Forde

The story of Islamic medicine is one not only of transmission and translation, but also of innovation and change, evolving over the centuries into a truly sophisticated science.

The Royal College of Physicians holds a rare collection of Islamic medical manuscripts dating from the 13th century. This exhibition presented the newly researched collection for the first time and explored the medical traditions that developed in the heart of Islamic medicine from the 9th century to the 17th century.

The Western medical tradition emerged in the 5th century BC, although earlier civilisations such as those of Ancient Egypt and the Ancient Near East also developed medical techniques. Islamic medicine drew heavily on ancient Greek knowledge, especially humoral pathology. The exhibition opened with a display on the prominent Roman physician and philosopher, Galen (cAD 129–216), who classified the medical doctrine which states that the body’s health depends on the balance of the four humours: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm.

The exhibition continued with the exploration of anatomy; at the time an unknown frontier, through to the influence of magic and divination on early clinicians and the exploration of alchemical tradition in order to develop new medical theories. Throughout the Renaissance, Arabic learning was the dominant medical trend. It was during this period that the RCP was founded in 1518.

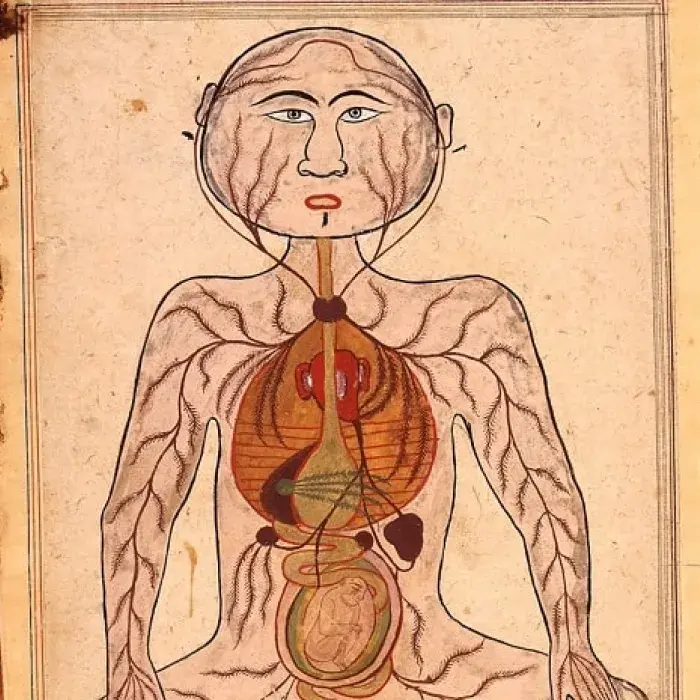

Although anatomical illustrations already existed in the medieval Islamic world, the earliest known illustrations of the whole body appear in a treatise called Manṣūr’s Anatomy by 14th century Persian physician Manṣūr ibn Ilyās. Manṣūr’s illustrations display the five anatomical systems: the bones, nerves, muscles, veins and arteries; and also sometimes the reproduction system. They mark significant progress in the development of anatomical depictions in medical texts.

However, these illustrations also pose a considerable mystery to historians of medicine. There are significant similarities between the anatomical figures in Manṣūr’s Anatomy and recently rediscovered illustrations from earlier Latin medical texts from the 12th and 13th centuries.

The exhibit looked at clinicians such as Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) a towering intellectual who came from Hamadan in Persia and Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyāʾ al-Rāzī, better known as Rhazes in the West. Perhaps the greatest clinician of the medieval world, Rhazes was responsible for many medical innovations. He remained famous in Europe until the 19th century and beyond.

The exhibition catalogue can be purchased from the RCP shop