Booksellers’ catalogues are a real treat for anyone interested in rare books. They often contain beautiful photos, detailed bibliographic descriptions and information about authors and the contexts in which books were published. As part of my placement at the RCP, I had the privilege of poring through a couple of booksellers’ catalogues for historical books about medicine that could be added to the RCP collection. During my hunt, I came across The presages of life and death in diseases, in seven books (London: Printed for G. Strahan, 1746) by Prospero Alpini, which took me on journey to uncover some of Alpini’s treasures that are already a part of the RCP collection.

Prospero Alpini (whose names also appear as Prosper, Prosperus, Alpinus and Alpino) was an Italian physician and botanist born in Marostica, Vicenza in 1553 and died in Padua in 1617. He is credited with introducing coffee and bananas to Europe and his writings on contemporary Egyptian medicine and botany provide an interesting addition to medical history.

Whilst medical adviser to Giorgio Emo, the Venetian consul in Cairo between 1580 and 1583, Alpini extensively studied Egyptian botany. Alpini’s best known botanical work is De plantis Aegypti liber (1592, ’Book of Egyptian of Plants’), which included the first European botanical accounts of coffee, banana and a genus of the ginger family later named Alpinia. De plantis exoticis (1627) was published after his death and expanded on the material in De plantis Aegypti liber.

Alpini also studied current Egyptian medical practice. This work was published in De medicina Aegyptiorum (1591, ‘Of Egyptian Medicine’). His research in this field culminated in his widely acclaimed work on the prognosis of diseases: De praesagienda vita et morte aegrotontium (1601, ‘The Presages of Life and Death in Diseases’). This is an interesting example of early diagnostic science.

The RCP collection contains a number of works by Alpini, including four copies of three different editions of De medicina Aegyptiorum. The two copies of the original edition published in 1591 provide a nice example of how vastly different two copies of a historical book can look.

Binding

The two copies of De medicina Aegyptiorum pictured were printed at the same time by the same publisher, but from the outside they look entirely different. Their binding (the covering, decoration and way it was constructed) is what differs vastly, and it is this that indicates the different journeys that these books have been on since they were printed.

Books were often bound and rebound with various materials at different points in their life. A has been rebound a number of times since its creation whereas B is contained in what may be one of its first bindings. A is covered in brown leather stamped with the name ‘Edward Gwynn’ in gilt lettering, as a way of marking ownership. It has also been rebacked at some point with the Royal College of Physicians stamp added to the spine.

B is covered in a simpler binding of limp vellum (made from stretched and treated animal skin, likely calf skin in this instance) which was a quick and cheap way of providing short-term protection, with no front and back boards and the supports still visible. This less protective covering is evident in the deterioration of B’s text block in comparison to A’s text block – there has been more damage to the edges of the paper, more cockling and distortion and the sewing at the spine is more fragile.

Provenance

These two books also provide interesting examples of varying provenance – evidence left behind by previous owners such as book plates and notes in the margins.

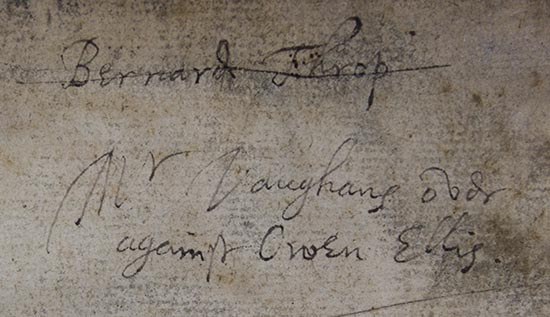

The words ‘de Brina’ are inscribed on the title page of A. This could be the autograph of a previous owner, or a note to remind the owner what the book is about. B contains an autograph of ‘Bernard Throp’ which is crossed out and replaced by that of a ‘Mr Vaughans’.

Both A and B also contain annotations, notes, symbols and underlining, known as ‘marginalia’. Marginalia serves as fingerprint traces (sometimes quite literally) of the people who have read and owned a book hundreds of years before you. They can give us exciting insights into the minds of those who wrote them, and provide understanding of the reception of the ideas contained within a book. It is fun imagining: who wrote these words? Were they physicians? Botanists? Was it more than one person? What relationship did they have with the book? What do their codes and symbols mean? Did they like what they were reading or did they vehemently disagree with the author?

The RCP’s two copies of De medician Aegyptiorum provide interesting examples of the importance of analysing and inspecting rare books as physical objects as well as studying the ideas contained within their content. What started with a search of booksellers’ catalogues for potential new acquisitions, turned into a brilliant hands-on experience which taught me a lot about aspects of a book’s physical make up such as binding and provenance. These things can deepen our understanding of the history of the concepts within a book and the reception of these concepts. It has been a great experience working with the Prospero Alpini works in the RCP library, which can be consulted by appointment in the library reading room.

Sally Nicholas, MA placement student