As part of the Institute of Historical Research History Day 2022, today we’re taking a look at materials from the RCP archives and museum relating to Edward Jenner (1749-–1823) and the spread of vaccination.

Jenner developed and a new method for preventing smallpox. Inoculation was already a known procedure: that’s when they would infect you with a small amount of smallpox itself. But with Jenner’s method – called vaccination – the patient was infected with the cowpox virus, which was safer, and gave the patient immunity against smallpox. Jenner wasn’t the first person to discover that people who caught cowpox became immune to smallpox – farm and dairy workers had known this for centuries – but he was the first scientist to publish a paper on the subject.

A Jenner notebook in our archives runs from 1787 to 1806, and as well as his observations of the natural world and even a few pathology sketches, it includes records of Jenner’s conversations with rural workers about their health and healthcare.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t really go into cowpox or smallpox much in the notebook that we have, but his notes do show his practice of travelling around the countryside and learning from the local people. In March 1796, he was investigating certain lung diseases, like tuberculosis, and he theorised that they could be caused by parasites passing from animals to humans. He learnt the story of a Mrs Self, who used to work in a butcher’s shop.

‘Mrs Self complained to Mr Hands that she was

tried with a troublesome cough & that she frequently

cough’d up little worms, similar to what she had

often seen in the lungs of hogs when she lived with

her father. Now, as this woman was the Butcher’s

daughter & had frequently been employed in the

shop in the distribution of the Haslets etc’ –

haslet is a minced pork product, like a meatloaf –

‘is it not probable that these animalculae’ –

little animals! – ‘or their eggs, are transferrable

from the hog to the human species.’

Jenner identifies the worms as Ascarides. The condition is called ascariasis, and the symptoms can be like asthma or pneumonia; if the worms migrate into the intestine, it can lead to vomiting, diarrhoea, and weight loss.

Jenner definitely seemed to feel he was onto a winner with the idea that parasites cause TB. A couple of pages on, he asked himself, in this sweetly robotic way:

‘Query? – Does tuberculous consumption arise from our familiarity with an animal that nature intended to keep separate from man.. (vide obs: on the cowpox)’

The observations on cowpox he refers to are in another notebook which isn’t in our archives.

The language Jenner uses about ‘unnatural’ contact between humans and animals might remind you of how some people talk about the seafood market where Covid started and theories about it spreading from animals to humans. The echoes of Covid in these documents don’t stop there: find out about ‘anti-vaccinist’ opposition to Jenner’s ideas in this video about one of Jenner’s letters.

Watch our short Jenner film:

The surgical scalpel blades with a handle inscribed with the name ‘Jenner’ are object X662 in our museum.

These blades were recently tested by a team of scientists from McMaster University, Ontario, and the Mütter Research Institute, Philadelphia, who are studying the global evolution of smallpox and its prevention. They’re testing for virus molecules on these blades and others in institutions around the world, to determine the range of viruses used for vaccination in the past.

You can find out all about their research in their own words in this event from 2021.

They’ve detected traces of virus on the blades, but they haven’t yet been able to identify what type of virus it is, so watch this space for updates.

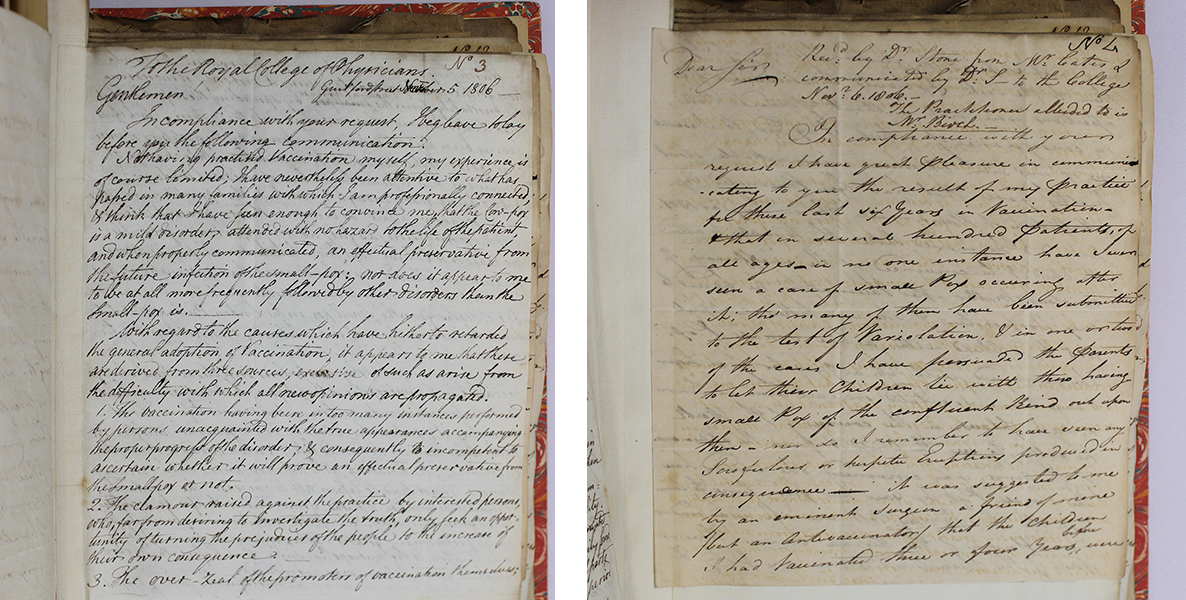

Thinking about early vaccination against smallpox, you might wonder what the RCP’s role was in all that. At that time, the RCP as an organisation was usually pretty sceptical when it came to new medical discoveries or techniques. For example, we were very disapproving of germ theory, and the invention of the stethoscope. So, it’s maybe surprising that we got fully behind vaccination early on. In 1806, the government asked the RCP to report on the efficacy of vaccination.

The RCP wrote to licenced doctors across Britain, asking for their views on vaccination, and we have three volumes of their replies.

Responses were mixed. John Sims didn’t see why a new-fangled vaccination technique was needed when, as far as he was concerned, the older inoculation procedures worked perfectly well. He talked about ‘the over-zeal of the promoters of vaccination’ and felt that the public would lose faith in doctors if they keep chopping and changing like this:

‘this change of sentiment has lessened the value of medical evidence, the public being ready enough to conclude that practitioners either deny or avow a fact, as best suits their present views.’

But, John Cates was a definite convert – possibly one of these overzealous promoters that Sims was thinking of, and ethically dubious:

‘I have great pleasure in communicating to you the result of my practice in these last six years in vaccination, & that in several hundred patients, of all ages, in no one instance have I ever seen a case of smallpox occurring after it[.] […][I]n one or two of the cases, I have persuaded the parents to let their children lie with those having smallpox of the confluent kind out upon them…’

He meant that he was exposing healthy children to children who were already ill with smallpox and had visible rashes. He went on to describe all the lengths he went to in infecting vaccinated children, but to no avail.

On balance, the evidence was that vaccination worked, and the RCP helped set up the National Vaccine Establishment, the body that organised the national vaccine rollout.

This wasn’t without consequence for the college, which opened itself up to ridicule from satirical cartoonists. Currently on display in the exhibition ‘A taste of ones own medicine’ (open until 2 December 2022) is a print titled ‘The Cox Pox Tragedy’ It shows a cow’s funeral procession, as it leaves the old RCP building; the RCP appears to be collapsing in the background as its reputation as a bulwark against quack medicine is undermined by its support for the radical new treatment.

Jenner himself was never a member of the RCP. He was a surgeon by training, not a physician, so would not have been eligible for membership. After he became successful and famous, the college invited him to join, possibly to bask in some of his reflected glory. But Jenner was not charmed by the offer and declined.

Felix Lancashire and Katie Birkwood

Anyone can come and use our collections. You can search our library, and archive and museum catalogues online, and make an appointment

by emailing history@rcp.ac.uk