Lady Dufferin, Photographer Bourne and Shepherd, 1884-1888. Image from ‘Lady Dufferin and the Women of India’, The Strand Magazine (Nov 1981), 2(11): 459-462

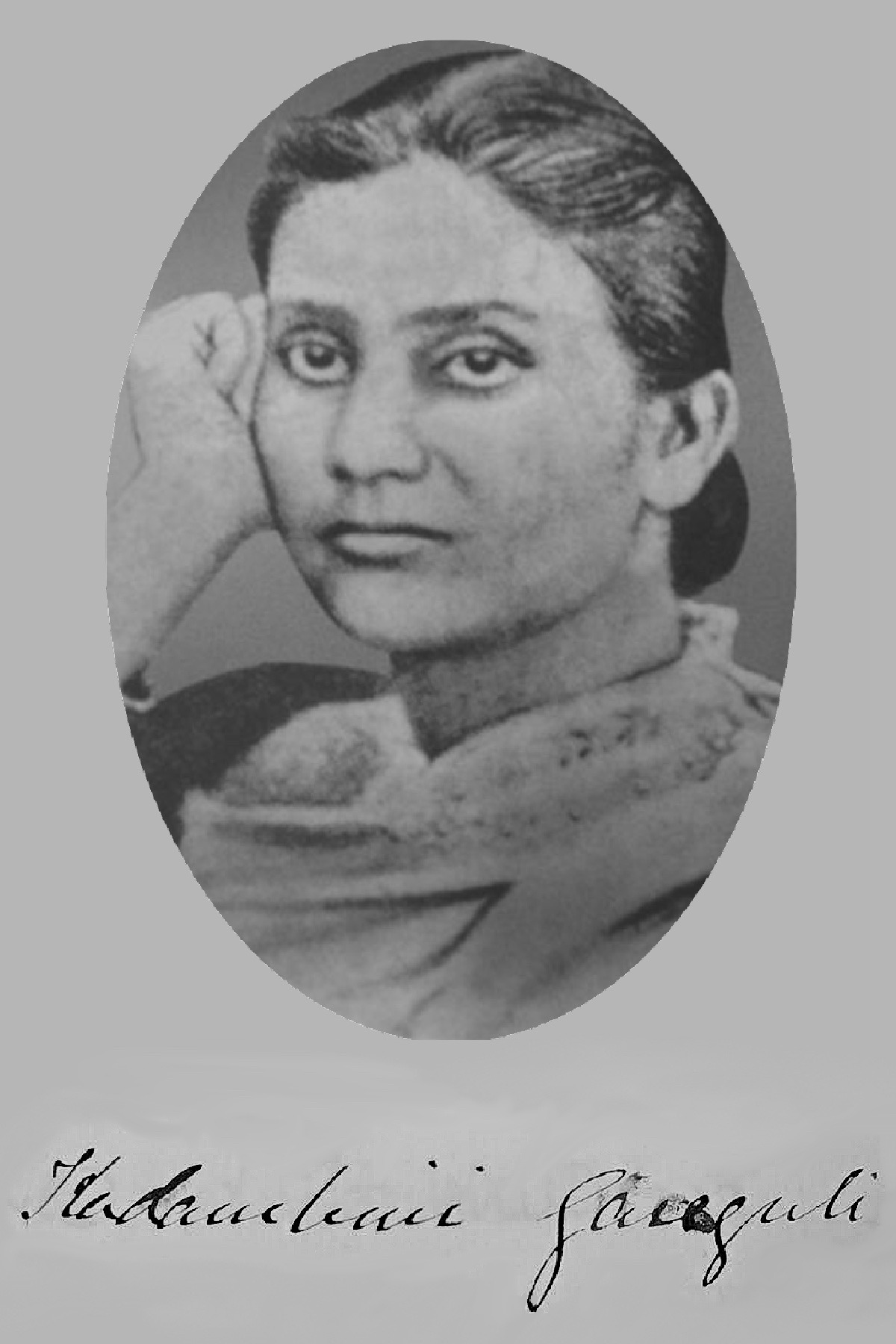

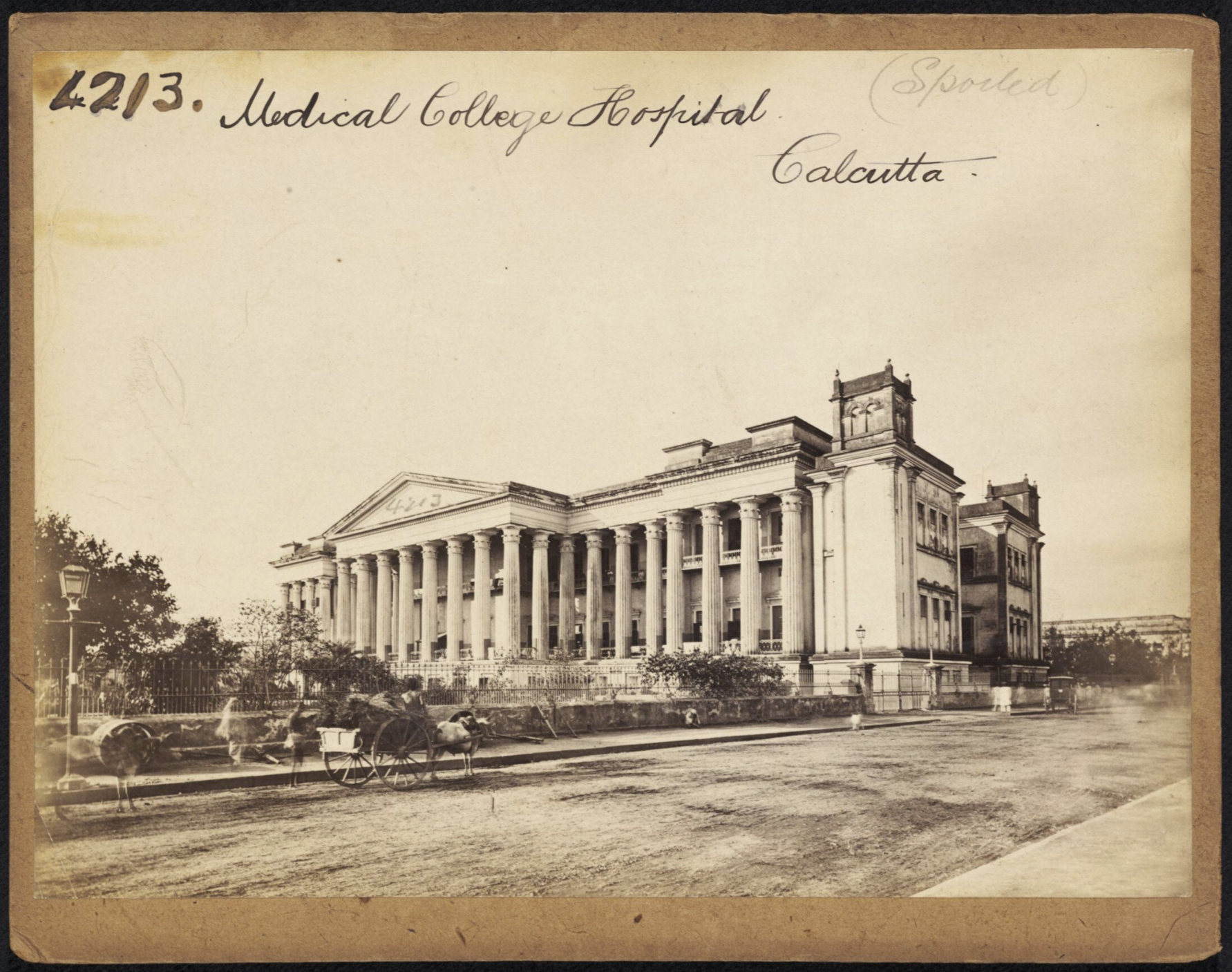

Word of Kadambini’s perseverance in her medical studies had reached Florence Nightingale, who went onto recommend Kadambini to Hariot Georgina Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, patron of many Indian hospitals. In 1888, Kadambini was appointed to the Lady Dufferin Hospital in Kolkata on a monthly salary of Rs.300. However Kadambini was denied the responsibility of a ward, which was the only way to gain clinical experience and skills. A medical role of that seniority was predominantly allocated to European women, with Indian women doctors working under them as assistants. Frustrated and angered by this injustice, Kadambini wrote a public letter to the local newspaper.

The difficulties Kadambini experienced as a doctor also extended into her community. For she was viewed and treated no more than an untrained midwife by the local people, who disregarded her medical education and training. However there were some orthodox Hindu men who viewed and feared Kadambini’s success, perceiving it as a direct threat to their masculinity. In 1891, the orthodox magazine Bangabasi indirectly called Kadambini a ‘whore’. Despite being married and a mother, identities that are respected within the Indian culture, they failed to protect her against this sexist abuse. Dwarkanath and Kadambini took the editor of Bangabasi, Mahesh Chandra Pal, to court and won. Mahesh was fined Rs.100 and sentenced to six months imprisonment.

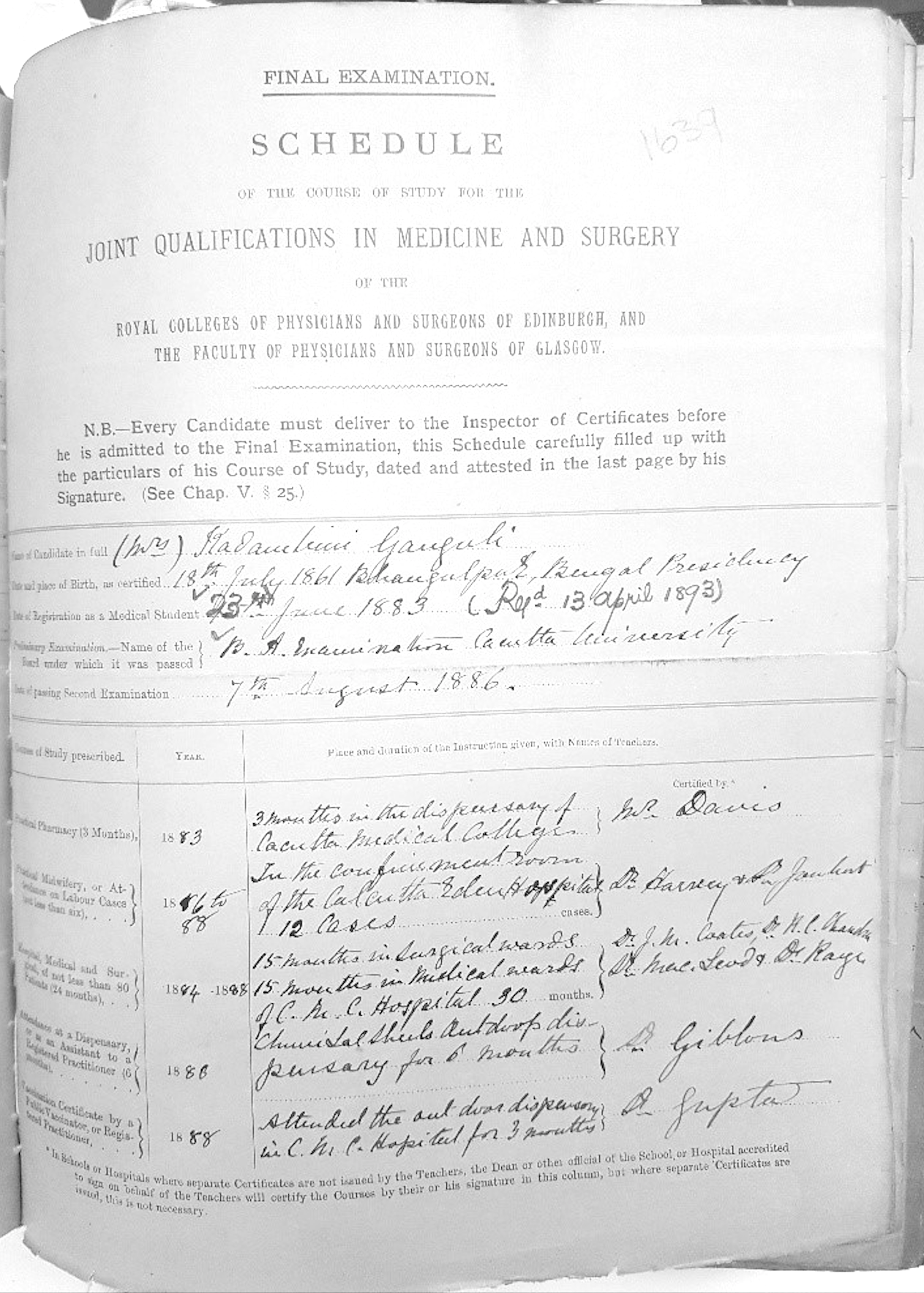

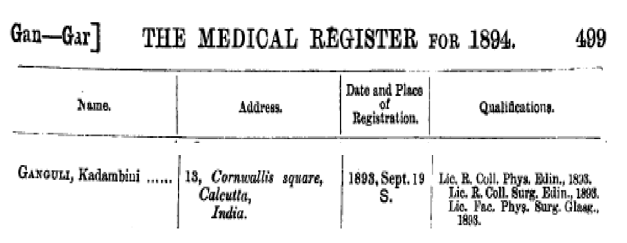

In a society shaped by colonial and patriarchal oppression, Indian women professionals were rarely accorded the respect and attention their White or Indian male colleagues received. After several years of being treated as inferior to other doctors on the basis of race and gender, and the lack of an MB degree, Kadambini decided to pursue further medical qualifications in Britain. For she hoped that in acquiring a British qualification she would finally receive equal treatment in the workplace.