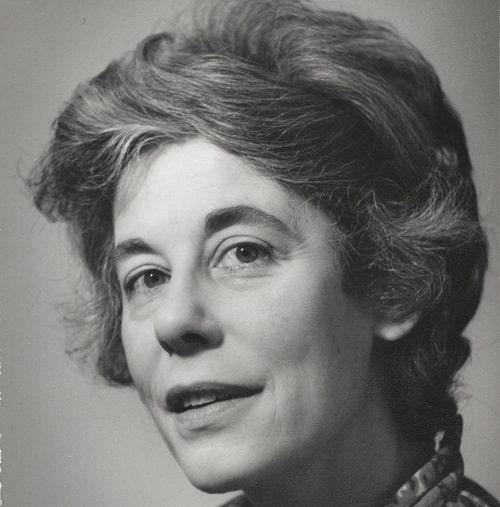

Sula Wolff was a pioneer of child psychiatry in Britain. She used to say that she grew up in Berlin as a ‘pavement child’ – playing on the streets with the city’s urchins, and, as an only child herself, observing their behaviour with a fascination that never left her. It was this curiosity about the lives of others that informed her later work. She combined her clinical expertise with an abiding curiosity about her subjects. Her surgery was not only lined with books, it had a sand-pit in the corner. Every encounter with a child became, for her, a research project.

She was amongst the first in her field to identify and define the characteristics of children on the autistic spectrum, and to establish their genetic component. By studying both the environmental factors, such as early maternal deprivation, which led to emotional disturbances in children, as well as the hereditary element which informed their behaviour, she was able to categorise the different manifestations of the unusual child, which might range from severe autism to the milder Asperger’s syndrome, and which needed to be treated accordingly. Her seminal works, such as Children under stress (London, Allen Lane, the Penguin Press, 1969) and Loners: the life path of unusual children (London, Routledge, 1995) have become classics of their kind.

For all the expertise she developed, however, she never lost sight of the welfare of the child. As one of her colleagues put it: “She took children’s anxieties and difficulties seriously and taught never to underestimate the importance to the child of trying to see the world though their eyes. She helped children to be understood, and she helped parents to understand their children better, and, more often than not, to begin to understand their own childhoods.”

She was born in Berlin, the only daughter of Walther and Friedel Wolff née Saloman, and brought up in the German town of Wetzlar. Her father was a patent lawyer, and her mother, from whom she inherited her strong aesthetic sense, was a stylish figure in the town, a maker and wearer of beautiful clothes. As a Jewish family in the 1930s they were keenly aware of the threat to their existence, and when, in 1933, Walther was briefly apprehended by the Nazis, he took an immediate decision to leave. He went ahead to find sanctuary in Britain, a country for which he had a deep admiration, while Sula and her mother followed, staying first with an aunt in Rotterdam, and then joining Walther to live in Hampstead, which was to be her parents’ home for the rest of their lives. There they harboured some fellow Jews – but many of their relatives were not so lucky as they had been, and perished in Nazi camps.

As a well-educated German girl, Sula arrived in Britain already speaking English, and became a pupil at South Hampstead High School, where her aptitude won her the top English prize, and, later, entry to Oxford University. The school was evacuated to Berkhamsted during the war – an experience she loved because, quartered mainly with Quaker families, she felt herself liberated from her somewhat constraining home life. She had long decided to be a doctor, and at Oxford studied medicine, working first at the Radcliffe, then later, as a postgraduate, in the burns unit in Liverpool, before transferring to the Whittington Hospital in London, where she trained as a paediatrician alongside Simon Yudkin [Munk’s Roll, Vol.VI, p.488], from whom she acquired a passion for equality of provision and the virtues of the NHS. The harrowing experience of seeing children treated for meningitis by having penicillin injected directly into their cerebrospinal fluid convinced her that she must do more for damaged children; later she would make a special study of those who had been born deformed by thalidomide.

She went to the Maudsley Hospital, where she studied child psychiatry under the formidable psychiatrist Sir Aubrey Lewis [Munk’s Roll, Vol.VI, p.284], and deliberately took LSD to study its effects. There too she met her future husband, Henry Walton, later emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh, a South African who had been invited over to London by Lewis after seeing his MD thesis on attempted suicide. When Walton went back to South Africa to work as head of psychiatry at Groote Schuur Hospital (he had been Christiaan Barnard’s best man), she went too. They married in Cape Town in 1959, and she went on to be the first child psychiatrist in the Cape.

Just as the Wolffs had fled Nazi oppression, so the Waltons found apartheid increasingly oppressive. In 1960 they left for America to work as research fellows at Columbia and Brooklyn respectively. In 1962, Henry was invited back to Britain to be professor of psychiatry in Edinburgh, and Sula was appointed to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, where she worked clinically in the NHS, later becoming a senior registrar.

While her husband was always sought out for jobs, she had to find them for herself. She was always modest about her abilities, but single-minded in what she wanted to do, which was to work with problem children and their families. She believed that early intervention was vital. The first sentence of her introduction to Children under stress reads: “With rare exceptions, problem children are no different from other children.” Later, however, as her research work took her into the area of genetics, and hereditary conditions such as autism, she would modify that view, while never losing sight of the central humanity of the child she was dealing with. Her writing was always exceptionally clear, spare, and elegant but rigorous, just as she herself was. Even in ordinary conversation, she would never let sloppy statements or ill-defined judgements pass. A series of clinical papers and books on various aspects of child psychiatry established her reputation as a seminal influence in the field. The chapter she wrote in Loners on the schizoid personality of Ludwig Wittgenstein has been widely admired. Throughout her career she taught medical students, young psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers; she was one of the first to promote liberal visiting hours for parents with children in hospital. She was made an honorary fellow of the department of psychiatry at the University of Edinburgh, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and the Royal Society of Medicine.

Her long and loving relationship with her husband Henry was founded on opposites: she was the restrained rationalist – he was the extrovert. She was an expert cook, regarding her immaculate, green-walled kitchen as her ‘laboratory’. She always refused help (“It’s because she’s an only child”, Henry would say if guests erred by attempting to help carry out used dishes). What they shared was a love of art, and their extensive art collection, drawn from contemporary artists, but also from China and Africa, filled their famously beautiful house at Blacket Place. It is now in the National Galleries of Scotland.

Shortly before her death, the Waltons moved into a smaller flat in Edinburgh, keeping only a small collection of their favourite works. Sula Walton died after developing leukaemia. They had no children.

Magnus Linklater

[The Times 5 October 2009, 8 October 2009; The Guardian 22 October 2009; The Independent 2 November 2009; The Scotsman 11 January 2010]