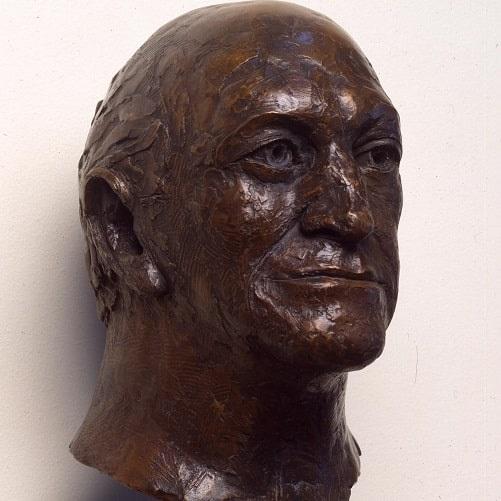

The bust of Bill Hoffenberg (no one ever called him Raymond) by Elisabeth Frink suggests a man of vision, determination and courage and, in that, it truly reflects the man he was. These were the qualities he showed in his opposition to the apartheid regime in South Africa, and later in his career as professor of medicine at Birmingham, as president of the Royal College of Physicians and of Wolfson College, Oxford. The broken nose, injured both at rugby and boxing, is a reminder of his passion for sport, but the smile of welcome of the man who lived life to the full and who so loved convivial occasions is not revealed here. Bill was a liberal in the best sense of the word. He was successful in almost everything he cared about and when he cared, he cared passionately. He was disappointed with his record in laboratory research and in his inability to halt the NHS reforms (which he deplored) which were suggested by the US economist Alain Enthoven and implemented by Kenneth Clarke and Margaret Thatcher, but not by much else.

Born in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, the son of Benjamin Hoffenberg, a company director, and his wife Dora née Kaplan, Bill thrived at school both in sport and work, matriculating for university at only 15. He spent the extra year in advanced mathematics, Afrikaans literature and a little Greek, before entry to the medical school at the University of Cape Town in 1939. At the outbreak of war, when under age, he doubted his father would give permission for him to join up and so had to forge the necessary parental signature. He served as a stretcher bearer in the Sixth South African Armoured Division in Egypt and Italy, through Rome, Florence and Bologna.

On his return to Cape Town, he lived the life of a typical medical student of the time, never neglecting the opportunity to have a party. He had a formidable reputation as a host and someone who could, if challenged, drink others under the table. But even after such a party, he was always up early in the morning, regularly putting in three hours of work before breakfast. A fine sportsman, he represented the university in golf, tennis, squash and water polo, and was no mean rugby player and boxer. He graduated second in his class in 1948. At this stage an academic career was not in Bill’s mind, but he was inspired by the legendary bedside skills of his chief, Frank Forman. In the early 1950s he went to England to join the course at the Postgraduate Medical School at Hammersmith Hospital, at the end of which he was appointed as a senior house officer to Russell Fraser [Munk’s Roll, Vol.X, p.149] and later as a registrar to Raymond Greene [Munk’s Roll, Vol.VII, p.228] at New End. There began his interest in endocrinology and in thyroid disorders in particular. After passing the MRCP he returned to Groote Schuur as a registrar on the medical unit. Then was the time to think about research.

He began with clinical work on Sheehan’s and Turner’s syndromes, the latter earning him his MD. A Carnegie fellowship took him to America to learn about the use of isotopes in endocrinology. Later, though, looking back at his overall career in research, he confessed that he had “dabbled without the commitment of a dedicated research scientist…and could not lay claim to any outstanding contribution.”

In the early 1950s Bill had the stance of most white South Africans, that politics was not his business, but in 1953, after witnessing policemen beating up a lone innocent black man and seeing the results of such beatings in his patients, he turned the corner and joined Peter Brown, Leo Marquand and Alan Paton in the Liberal Party. Bill became increasingly involved, leading a campaign against solitary confinement of political prisoners and becoming the major supporter of the National Union of South African Students. It was perhaps his chairmanship of the Defence and Aid Fund (which provided for the defence of those accused of political crimes) that led to his becoming, in 1967, the 683rd person to be banned. This meant that he could not continue in any capacity at the medical school. He could no longer stay in South Africa and accepted the offer of a post at the National Institute of Medical Research at Mill Hill, prior to a clinical appointment at the new Clinical Research Centre which was to open two years later at Northwick Park. At his departure to the UK he was seen off by a crowd of more than 2,000, singing the National Anthem of South Africa.

At Mill Hill he began animal experiments on albumin metabolism which were not to his taste (“I didn’t want to be a dog doctor”), but he found solace with clinical work at New End and teaching at the Royal Free. In 1970 he moved to Northwick Park, where his research continued to fail to inspire him and he missed students. Unhappy at the Clinical Research Centre, he was delighted to accept the William Withering chair of medicine at Birmingham in 1972.

There a major aim was to preserve excellence in clinical work and teaching, which he extended to involve the consultants in general hospitals of the region. A priority of his own teaching was to devote particular time to the weaker students. His own endocrine unit was to do distinguished work and chairs were created in cardiology, rheumatology, neurology and geriatric medicine. With David Heath he pioneered medical audit, providing the foundation of the Royal College of Physicians’ first report on the subject. He was a natural leader and his brisk and expert chairmanship of committees led to increasing demands for his services, for instance by the British Heart Foundation, the Mental Health Foundation, the UK Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research, the Medical Research Council, the Committee for the Safety of Medicines, the Medical Research Society, and locally in all the important committees of the regional health authority.

Such was his personality and reputation, it was no surprise when he was elected president of the College in 1983, an office he filled with distinction and a firm hand. Apart from promoting further medical audit, he led the College, among other things, into concerns about ethical issues in medicine, research fraud, relations between the profession and the pharmaceutical industry and issues about the end of life. He clashed with Mrs Thatcher on more than one occasion. She was, he said, the only person in his career to render him speechless when, with the presidents of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons and Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, he visited 10 Downing Street to discuss grave concerns about the state of the NHS. They were told that she would deal with them as she had with the miners and the miners’ leader, Arthur Scargill. More widely quoted is his letter to The Times concerning the introduction of the internal market in the NHS (disastrous in his view), saying that the Government had reversed the usual procedure of “Get ready, take aim, fire” to “Get ready, fire, take aim”.

His last years as president of the College of Physicians overlapped with his presidency of Wolfson College Oxford. This was a particularly happy time in which Bill enhanced even further his reputation for benign, yet firm leadership, for concern for students and for brisk effective conduct of committee work. After his death Wolfson College looked back to him with a glow of affection and with admiration for his character and achievements.

Bill and his wife, Margaret née Rosenberg, followed their sons Derek and Peter to Australia in 1993 and there Bill, ever active, was appointed to the chair of medical ethics at the University of Queensland. He had been interviewed by telephone when in Oxford and when he confessed that he could teach only from his long experience as a physician in two countries, he was greeted with “Thank God – all the other applicants are philosophers!”

Throughout his career Bill was widely regarded with respect, admiration and affection. One of the issues about which he felt particularly passionate was that of euthanasia. This was reflected in his decision to defend Nigel Cox before the General Medical Council. Cox, a man Bill admired, had been found guilty of attempted murder, having ended the life of a patient in agony by the injection of potassium chloride. A firm supporter of Lord Joffe’s proposals to the House of Lords on assisted dying for the terminally ill, Bill wrote persuasive and logical refutations of the arguments put forward by Joffe’s opponents. In public, Bill was discreet in what he wrote, but privately he deeply regretted the disappearance of Brompton mixture (which contained morphine, cocaine and sometimes other narcotics in an alcoholic solution), and past practice by which doctors did not hesitate to use it or opiates to ease the passage to death, when they and nursing colleagues thought it appropriate. Indeed, when his own death was found to be inevitable, he asked who could be found to give him morphine, though he would not admit to pain. Such treatment being denied, he decided against taking further medical advice and instead stated that he would neither eat nor drink (beyond moistening his mouth) until he died. This programme he followed remarkably closely, without distress and in remarkably good humour, until his death only a few weeks later. He is survived by his second wife, Madeleine née Douglas, whom he married in December 2006 after the death of his first wife, his sons and his grandchildren, Sophia, Imogen and Oliver.

J G G Ledingham

[Clinical Medicine Vol.7 No.6 Dec 2007, p.7; College Commentary June 2007 pp.8-9; Medicine, Conflict and Survival October-December 2007; 23(4):314-315; The Lancet 2007 369 1854; The Independent 24 April 2007; The Times 25 April 2007; The Daily Telegraph 9 May 2007; Western Morning News 10 May 2007; The Courier-Mail 23 May 2007; The Guardian 29 May 2007]