Born at Mount Vernon, Lanarkshire, John William was the only son of John McNee of Glasgow and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Little is known of his family background; the death of a sister in 1939 from streptococcal septicaemia is noted in his correspondence. He was educated at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and at Glasgow University, where he qualified in medicine with honours. After graduation he held appointments as lecturer in pathology under Sir Robert Muir [Munk’s Roll, Vol.V, p.298], and as assistant to the regius professor of the practice of medicine in Glasgow. Awarded a McCunn scholarship in 1911 and a Carnegie research fellowship in 1912, he went to Freiburg where, under the direction of Aschoff he worked on the aetiological classification of jaundice and the role of the reticuloendothelial system in the metabolism of bile. In 1914 he obtained his doctorate with honours, and the John Hunter and Bellahouston gold medals.

During the first world war he served in the RAMC, attaining the rank of major and acting as asistant adviser in pathology to the First Army in France. He undertook important clinical and pathological studies on trench fever and gas gangrene with J Shaw Dunn; on war nephritis; and on chlorine poisoning - in which he carried out one of the first, if not the first, autopsy on poison gassed soldiers in France. His work pointed the way to more effective preventive and therapeutic measures for ameliorating conditions among the troops. For his war services he was awarded the DSO, mentioned in despatches, and in 1920 was made a commander of the Portuguese Military Order of Avis.

Having obtained his DSc, he moved to London where the new medical unit had been established at University College Hospital under the direction of T R Elliott [Munk's Roll, Vol.V, p.119]. It caused some surprise that the two first assistants appointed were McNee, regarded essentially as a pathologist, and F M R Walshe, a neurologist, later Sir Francis [Munk's Roll, Vol.VI, p.448]. The latter soon moved away into consulting practice, but McNee remained, to continue his research on diseases of the liver and the gall bladder for which his training in pathology had provided a sound basic scientific background. His considerable skills as a physician and a teacher soon became apparent. In 1924 he obtained a Rockefeller fellowship and went to Johns Hopkins as an associate professor, at a time when the syndrome of coronary artery thrombosis was being defined. On his return he published in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine, 1925, the first description in Britain of this condition, with the encouragement of Elliott and Sir Thomas Lewis [Munk's Roll, Vol.IV, p.531]. At this time he elected to abandon a purely academic life and moved into full-time consulting practice, while remaining a physician to UCH. His reputation as a sound and sympathetic clinician brought rapid success and his advice was widely sought, especially on difficult cases of liver and biliary tract disorders. He was called upon to give prestigious lectures by Royal Colleges and learned societies, and further consolidated his reputation by the publication, jointly with Sir Humphrey Rolleston [Munk's Roll, Vol.IV, p.373], of the classical textbook Diseases of the liver, gall bladder and bile ducts, London, Macmillan & Co., 3rd ed. 1929. It appeared that his future in London was secure and permanent.

But, in the middle 1930s, the regius chair of the practice of medicine in Glasgow fell vacant and McNee was invited to accept it. Locally there was some resentment that the post should not be filled by a distinguished Glaswegian physician. Moreover, in Glasgow McNee was remembered, even respected, as a pathologist rather than a clinician. McNee himself had two reservations: firstly, he would wish, if he moved north, to keep an option open to continue private consulting practice and, secondly, he insisted that he should be given an institute in which he could establish a research team. The University agreed to his first condition, and the second was made possible by a handsome bequest from Gardiner, a local shipowner, after whom the institute would be named. Thus it was that McNee, satisfied on both counts, accepted the regius chair and moved back to Scotland.

Back in his alma mater, despite a lukewarm welcome, McNee aimed at becoming a first class professor, and at setting up a first class department. His efforts to raise the standard of medical education and examinations in Glasgow met with some antagonism, and his appointment of a paediatrician as his senior lecturer was not well received. His insistence that all his juniors should obtain the MRCP(London) rather than the Glasgow FRFPS, although forward looking, did not go down well.

McNee threw himself enthusiastically into the creation of a new department of medicine attached to his wards at the Western Infirmary. Here he had magnificent offices, consulting rooms, six research beds with their own diet kitchen, and very ample laboratory space. He was probably the first professor of medicine to establish an animal laboratory within his department, and to encourage his staff to work on experimental pathology. Although, as had been promised to him, the Institute provided the necessary facilities, in the event he saw few private patients there. The scene was therefore set for the establishment of a first class research unit, and McNee’s expertise as a lecturer, clinical teacher and ‘beloved physician’ were at last beginning to be appreciated when war broke out in Europe.

In 1938, McNee had accepted with alacrity a request to become a naval consultant, with the rank of surgeon rear-admiral (given to few, if any, as he would recount in later life, who had previously been ranked as major, RAMC). He entered the senior service as consulting physician to the Navy in Scotland and the Western Approaches. He was proud of his new status and was not inhibited from sweeping up to the hospital in his WRNS-driven Rolls-Royce - gifted, incidentally, by a colleague, - to deliver a lecture or conduct a ward round in all his gold-braided glory. During the first year of the war, especially, McNee refused to sit idle, or only partially occupied at the naval base hospital near Aberdeen; it made more sense to him to remain in Glasgow and continue as much teaching and research as possible. This was barely acceptable to Navy top brass, who refused to sanction travel expenses to and from Glasgow since officially - officiously - he was permanently stationed in Aberdeen. But he worked hard at his naval duties, publishing useful data on wartime afflictions, especially immersion foot. He took an active part in the organization of medical staff and equipment for support ships accompanying North Atlantic convoys, and his contributions to this are recorded in The Rescue Ships by Vice-Admiral B B Schofield and Lieutenant Commander L F Martyn, Edinburgh, William Blackwood & Sons, 1968.

When the turmoil eventually ceased, McNee was faced with the task of starting up his research unit virtually from scratch. But the war had taken its toll and he had a limited time left in his chair. So, although he continued unabated with his teaching and clinical commitments, few research projects of significance were accomplished before his retirement in 1953.

He had always loved the countryside and sporting activities, especially field sports - though he was an enthusiastic golfer. He moved south to Hampshire where he and his wife nurtured a lovely garden. The death of his wife in 1975 left him lonely, and his gradually failing health caused him frustration. But he remained mentally alert to the end, and he could astonish his visitors to Winchester with an amazing flow of vivid reminiscences.

McNee was always a controversial character. His aristocratic appearance, patrician manner, and lavish lifestyle distanced him from a number of his colleagues and associates, both in London and Glasgow, but many of his students discovered him to be warm and sympathetic, and to his assistants he remained helpful, loyal and supportive. His lectures to undergraduates were memorable, delivered with clarity of expression and without notes, and laced with anecdotes which made the subject come alive. His ward teaching rounds are still remembered for the lucid exposition of the difficult case. He had an excellent rapport with his patients, towards whom he showed every kindness and consideration. As an examiner - and in this role he was very much in demand - he earned the nickname of ‘the smiling ploughman’ on account of his kindly and very fair approach, coupled nevertheless with a determination to maintain standards.

From 1929-48 McNee served the Quarterly Journal of Medicine in an editorial capacity. With D M Dunlop, later Sir Derrick [Munk's Roll, Vol.VII, p.l70] and L S P Davidson, later Sir Stanley [Munk's Roll, Vol.VII, p.l36], he produced the popular Textbook of medical treatment, Edinburgh, E&S Livingstone, 1939, which ran to several editions, the 6th being published c.1953. He also continued to update his textbook with Sir Humphrey Rolleston on liver disease, to its 6th edition in 1955.

His many prestigious appointments included physician in Scotland to two sovereigns, president of the Association of Physicians, 1951, and the British Medical Association, 1954, and master of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company of London, 1957-58.

In 1923 he married Geraldine Z Le Bas, MSc London, who was herself active in the field of medical science. There were no children of the marriage.

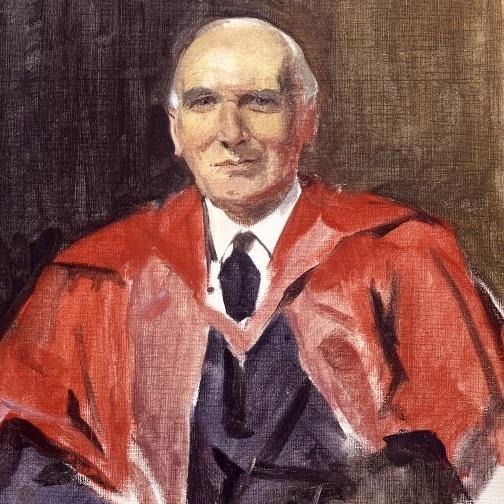

John McNee will be remembered as a benefactor of the College. Shortly before his death he made a gift of his Portuguese decoration, and in his will he bequeathed to the College one half of his residuary estate, together with his portrait by James Gunn, a smaller version of that which hangs in Glasgow.

S Howarth

[Brit.med.J., 1984,288,494,725; Lancet, 1984,1,408; The Times, 4 Feb 1984; 12 July 1954,31 Mar 1975; Portrait; J.roy.nav.med.serv., 1984,70,124; Glas.Med, 1984,2,4]