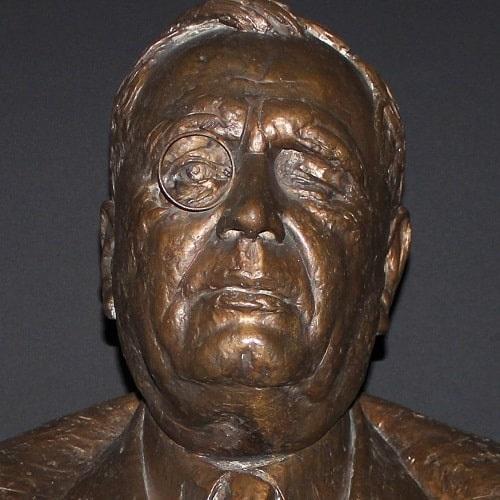

Sir George Godber was a former chief medical officer and a key figure in the creation of the National Health Service. A tall and imposing figure, he campaigned energetically against the evils of smoking and promiscuity - Sir Douglas Black [Munk’s Roll, Vol.XI, p.62] referred to him as a ‘medical lay saint’.

He was born in Bedford, the son of Isaac Godber, a farmer, and his wife Bessie Maud née Chapman, whose father, Thomas, was also a farmer. After attending Bedford School and he studied medicine at New College, Oxford and the London Hospital. He won a blue for rowing and twice took part in the boat race. He chose to specialise in public health medicine and went on to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to study for the Diploma in Public Health. In 1936 he passed the diploma and worked as county medical officer in Surrey before joining the Department of Health in 1939, where he stayed for the next 35 years, becoming deputy chief medical officer from 1950 to 1960, and chief medical officer from 1960 to 1973.

After qualifying in medicine in 1933, Godber held a variety of junior posts that gave him an insight into the state of the nation’s health in pre-NHS times. Working in a casualty ward in a municipal hospital in London’s Docklands, a GP practice in Limehouse, and an infectious disease hospital in Hampstead, he saw how many of his patients presented when seriously ill because they were too poor to go to the GP and too proud to ask for a free service. This experience profoundly affected him and led to his deep commitment to the NHS, as he said ‘We need to provide the most we can for the most people, not just the privileged few’.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, one of his first jobs was to organise maternity services in the suburbs for evacuees. Hospitals were forced to work together under the strain of dealing with so many civilian casualties and many of them were desperately inadequate and underfunded with grim buildings and ‘improvised’ operating theatres. When the Beveridge report was published in 1942, Godber became one of the team to prepare a survey of all British hospitals and he, personally, inspected over 300 in various parts of the country.

When the war ended it was obvious to all the political parties that a national health service was needed, but there was much confusion about how to set about it. Godber was one of those trying to reconcile the opposing parties and, in his view, it was the election of 1945 that was crucial – he wrote that this was ‘not because the idea of the NHS was a monopoly of the Labour Party – it wasn’t – but because it produced Nye Bevan as Minister of Health.’ Bevan recognised the central problem that no local authorities or trusts wanted to relinquish control of their hospitals, and he was powerful enough to persuade his cabinet colleagues to overrule this and introduce a fully funded national scheme that was free to everyone. In 1948 the NHS was born and Godber used to fondly recall how the papers were full of anecdotes about people asking their doctors to prescribe extra cotton wool and using it to stuff cushions or calling ambulances to take them shopping. One of his first achievements was to improve the distribution of consultants throughout the country and he also set up a confidential inquiry into maternal deaths in 1952. His influence was noticeable in the shape of the NHS in the 1970s and he liked to quote the American academic who called it ‘the finest bit of social legislation since the Magna Carta’.

A lifelong teetotaler and a non-smoker, he used his high profile position to campaign against smoking and promiscuity, and advance the need for precautionary vaccinations and for fluoridation of the water supply. In the early 1960s his tirades against tobacco – he described the cigarette as ‘the most lethal instrument devised by man for peaceful use’ – were not taken seriously at first but by 1965 an important change in the public attitude was achieved when the advertising of cigarettes on television was banned. His campaign against unwanted pregnancy was less successful – he admitted that ‘neither he nor anyone else had a clear idea of how to teach young people about sex’.

When he retired in 1973, he moved to Cambridge for, he said jokingly, ‘its excellent geriatric services’ and remained extremely active both in his own field and also giving lectures on Egyptian archaeology. He played two games of golf a week until he was 90 and drove a car until he was 97.

In 1935 he married Norma Hathorne née Rainey, the daughter of W Rainey who was a Clerk in Holy Orders. Of their seven children, four died young of a genetic blood disorder. One died in infancy and a son and daughter – seven year old twins – died in the same year as the NHS came into being but this did not deflect him from his task. Norma predeceased him in 1999 and he was survived by his sons, Colin and Steve, and daughter, Bridget.

RCP editor

[The Guardian 26 November 1973; The Guardian 1 July 1988; Daily Telegraph 11 February 2009; The Guardian 11 February 2009]