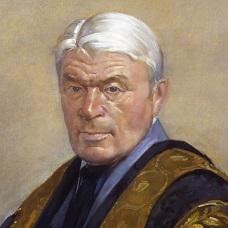

The passing of Cyril Clarke marked the end of the era of great medical all rounders. His career as a clinician ranged through life insurance practice, medical specialist in the navy, consultant physician and later professor of medicine in Liverpool, and, finally, President of the Royal College of Physicians of London. His research contributions were equally broad based, spanning his classical work on mimicry in swallow-tailed butterflies to his enquiry into longevity by tracing and studying the lifestyles of centenarians who had received congratulatory messages from the Queen.

He was one of the first in this country to appreciate that medical genetics, far from being a discipline which focuses on rare and esoteric diseases, has a major role to play across every aspect of day-to-day clinical practice. This led him to establish the Nuffield unit for medical genetics in Liverpool, which became a stable for many who went on to develop this field throughout the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

Cyril Clarke's most important contribution to medicine however, and one that reflects his flair and willingness to explore problems which were often outside his field of expertise, was his inspiring leadership of the Liverpool team that discovered how to prevent rhesus haemolytic disease of the newborn, one of the major advances in preventative medicine of the last half of the twentieth century. This work typified his unwillingness to be deterred by the gloomy prognostications of experts in their fields, who often told him that his thinking was way off the mark, and his instinctive gift for what Sir Peter Medawar [Munk's Roll, Vol.VII, p.330] called 'the art of the possible', reflected in his ability for sensing the quality of his younger colleagues and the science that they were pursuing.

Cyril Astley Clarke's father, Astley Vavasour Clarke, was a physician at the Leicester Royal Infirmary and one of the first to use X-rays in this country; his grandfather was senior surgeon to the same hospital. He was educated at Oundle, Caius College, Cambridge, and Guy's Hospital Medical School. After three years in life insurance practice, which allowed him time to indulge in his passion for sailing, he enrolled as a medical officer in the RNVSR and served throughout the war in the navy, ending his service by writing one of his first papers, on the neurological complications of malnutrition that he observed in British prisoners of war in Hong Kong.

After the war Cyril moved to Liverpool where he became consultant physician at the David Lewis Northern Hospital. Despite busy hospital and private practices he, together with his long-time friend and collaborator P M Shepherd, began a series of classical experiments on the genetics of swallow-tailed butterflies, work which later stimulated his interest in medical genetics. The success of the team of young clinical research workers that built up round him left him less time for his clinical practice, and he was appointed reader in medicine at the University of Liverpool and, in 1963 on the retirement of Henry Cohen [Munk's Roll, Vol.VII, p.106], he became professor of medicine, a post which he held until 1972. He founded the Nuffield unit of medical genetics, which he directed from 1963 to 1972.

On the year of his retirement he was elected President of the Royal College of Physicians of London, a post he held with great distinction and flair until 1977. From 1977 to 1983 he served as director of the College's medical services study group, and from 1983 to 1988 was director of its research unit. Among his many other activities he served as president of the Royal Entomological Society and, a post which pleased him almost as much as PRCP, president of the British Mule Society. He spent his later retirement in Liverpool continuing his work on the genetics of butterflies and in a characteristically broad range of medical research.

Cyril was a caring if slightly eccentric clinician, very much of the old school, who believed in minimal intervention. His advice to his new house staff on the use of drugs came, he claimed, straight from the mouth of one of his teachers at Guy's, who, as he got older, restricted his personal pharmacopoeia to morphia and sodium bicarbonate, and was not too liberal with the bicarbonate.

As professor of medicine he led his department with a light touch, preferring to let bright youngsters go their own way, but always around if they needed support. His remarkable flair and enthusiasm, and his ability to sniff out talent and to pick research areas of importance, was undoubtedly the major factor which led to the wonderful achievement of the rhesus team, and to the success of the department of medicine at Liverpool and its major influence on the development of medical genetics.

As a person Cyril was a complex mixture. He was a life-long schoolboy, constantly bubbling with enthusiasm and new ideas, and yet at the same time he could appear to be rather distant, so that his students and junior staff sometimes found him difficult to approach and a little terrifying. This was undoubtedly a reflection of his innate shyness; as they got to know him better his extraordinary warmth became apparent. He was extremely loyal to his staff and supported them throughout their careers, usually behind the scenes and often without their knowledge.

In 1935 he married Frieda, or Feo, as she was always known. Feo became an integral part of all Cyril's work and his many other activities, which ranged from crewing for him in his annual small-boat racing, not a relaxing pastime since Cyril had been an Olympic trialist and hated losing, to breeding swallow-tailed butterflies in captivity. It was a remarkable partnership; Cyril never fully recovered after Feo's death in 1997. They were survived by three sons, one of whom is a consultant neurologist.

Cyril's work was widely recognised. He was elected FRS and received many national and international awards. At the age of 88 years, still busy at his research, he wrote that he would very much like to know why butterflies have an XX chromosome complement in males and XY in females, yet the latter live much longer than the tempestuous XX males. 'God moves in a mysterious way' he concluded. Certainly there can have been few more mysterious phenomena than the multifaceted talents, flair, and complexity and warmth of character of the man who wrote these words.

Sir David Weatherall

[The Guardian 1 Dec 2001; TheTimes 8 Dec 2000; Brit.med.J., 2001,322, 367; The Daily Telegraph 30 Nov 2000; The New York Times 5 Dec 2000; The Independent 1 Dec 2000]