John Fothergill, M.D., was the second son of John Fothergill and Margaret Hough his wife, and was born at Carr End in Yorkshire, on the 8th March, 1712. He received his early education at Frodsham in Cheshire, and at Jedberg in his native county. About the year 1728 he was placed with Mr. Benjamin Bartlett, an apothecary at Bradfield in Yorkshire, and on the expiration of his apprenticeship proceeded to Edinburgh, then rising into notice as a medical school. He attended the lectures of Monro (primus), Alston, Rutherford, Sinclair, and Plummer, all students of the Boerhaavian school, and whose merits have been recorded by Fothergill himself in an account which he published in after life of Dr. Russell, his contemporary and associate. Dr. Monro discovered the powers of his pupil, and urged him to reside sufficiently long to obtain the doctorate; for till then he had only intended to qualify himself as an apothecary. He followed the advice of his preceptor; and took his degree of doctor of medicine at Edinburgh the 14th August, 1736 (D.M.I. de Emeticorum Usu in variis Morbis tractandis). Dr. Fothergill then visited London; attended the physician’s practice at St. Thomas’s hospital; and having taken a short tour, in company with some friends, through Flanders and Holland, returned to England about the year 1740, and commenced the practice of his profession in London. He was admitted a Licentiate of the College of Physicians 1st October, 1744, and is the first graduate in medicine of the university of Edinburgh who was admitted by the College.

Dr. Fothergill was a member of the Society of Friends, and through their influence and exertions he was soon introduced into business. His "Account of the Putrid Sore Throat attended with Ulcers, 8vo. Lond. 1748,"—a disease which produced a great mortality in and around London, and excited much alarm,—gave extended publicity to his name, and at once established his reputation. His progress onwards towards the most extensive and lucrative practice in the city was most rapid, and he is represented as having been for many successive years in the possession of a professional income of nearly 7,000l. To chemistry and botany he devoted his hours of relaxation and retirement. At Upton, near Stratford, Essex, he purchased an extensive estate, and furnished a noble garden, whose walls enclosed five acres, with a profusion of exotics, which he spared no pains in collecting. At an expense seldom undertaken by an individual, and with an ardour that was visible in the whole of his conduct, he procured from all parts of the world a great number of the rarest plants, and protected them in the amplest buildings which this or any other country had then seen. He liberally proposed rewards to those whose circumstances and situations in life gave them opportunities of bringing hither plants which might be ornamental and probably useful to this country or her colonies, and as liberally paid these rewards to all that served him. That science might not suffer a loss when a plant he had cultivated should die, he liberally paid the best artist the country afforded to draw the new ones as they came to perfection; and so numerous were they at last that he found it necessary to employ more artists than one, in order to keep pace with their increase.

His garden was known all over Europe, and foreigners of all ranks asked, when they came hither, permission to see it. Dr. Fothergill’s attention was not confined to the vegetable kingdom. Da Costa was indebted for many valuable remarks in his "History of Shells," of which Fothergill possessed the best cabinet in England, next to that of the duchess of Portland. His collection of minerals was more rare than extensive, and the gratitude of his numerous friends had supplied him with many curious specimens of the animal world. His collection of natural history was purchased on his decease by Dr. William Hunter, and is probably at this moment to be found in part in the museum which that distinguished physician bequeathed to the university of Glasgow, after having vainly solicited the ministers of the time to enable him to establish one in London. In 1754 Dr. Fothergill was elected a fellow of the College of Physicians of Edinburgh, and in 1763 a fellow of the Royal Society. His reputation soon extended to other countries. He was one of the earliest members of the American Philosophical society, instituted at Philadelphia. Linnæus distinguished by his name a species of Polyandria Digynia. The Royal Society of Medicine at Paris chose him an Associate in 1776; and his letters of admission were the more honourable because they included a request that Fothergill would nominate any persons of his acquaintance whom he might deem eligible to become corresponding members of the society. Vicq. D’Azyr communicated this mark of confidence in a Latin letter.

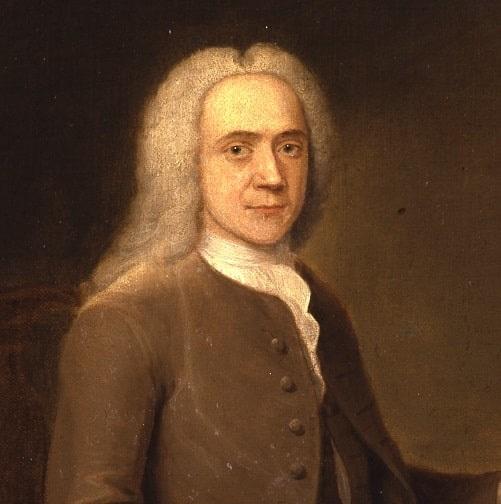

In December, 1780, Dr. Fothergill experienced a second attack of suppression of urine; two years previously it had been relieved, but no art could now remove it. The pain was very acute, the thirst insatiable, but his mind was as serene as in its best days. He expressed to a friend his hope "that he had not lived in vain, but in a degree to answer the end of his creation, by sacrificing interested considerations and his own ease to the good of his fellow creatures." He died at his house in Harper-street, Red Lion-square, on the 26th December, 1780, and was buried in the Quaker’s burial ground at Winchmore-hill. An exquisite full-length cabinet portrait of Dr. Fothergill, by Hogarth, is on the College staircase. It was presented by Mr. Cribb, of Covent-garden. An engraved portrait of him, by Green, after one by Stuart, is extant. "The person of Dr. Fothergill," writes his affectionate biographer, Dr. Hird, "was of a delicate, rather of an attenuated make; his features were all character; his eye had a peculiar brilliancy of expression, yet it was not easy so to mark the leading trait as to disengage it from the united whole. He was remarkably active and alert, and, with few exceptions, enjoyed a general good state of health. He had a peculiarity of address and manner, resulting from person, education, and principle, but it was so perfectly accompanied by the most engaging attentions that he was the genuine, polite man, above all forms of breeding.

At his meals he was remarkably temperate; in the opinion of some rather too abstemious, eating sparingly, but with a good relish, and rarely exceeding two glasses of wine at dinner or supper; yet by his uniform and steady temperance he preserved his mind vigorous and active, and his constitution equal to all his engagements." Dr. Fothergil's library and paintings were sold in 1781 in York-street, Covent-garden. His house and choice botanical garden of rare plants at Upton were sold in the same year. His collection of shells was purchased by Dr. William Hunter.

Dr. Fothergill contributed many papers to the "Gentleman’s Magazine," the "Transactions of the London Medical Society," &c. &c. These, with a Sketch of his Life, a Selection from his Correspondence, his Inaugural Essay, and his Treatise on the Sore Throat, were published by Dr. Lettsom in three volumes 8vo. In 1783.

William Munk

Post publication addition

In 1747 Frances Bladen left a share of a Nevis estate, called Jorey's, to each of six friends and relatives. Some or all of them sold or mortgaged their share to a London merchant James Buchanan. A one third share was granted to John Fothergill in 1763. In 1772 John Fothergill sold his share of Jorey’s, but it was mortgaged back to him later that year. In 1780, Fothergill, after the death of the mortgagee, appointed Charles Hutton on Nevis as his attorney to manage the estate. In 1791, John Fothergill, together with his aunt Ann Fothergill, sold Jorey’s’. It consisted of 320 acres together with 100 enslaved people.

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146665365 Accessed February 2021