David Pitcairn, M.D., was born the 1st May, 1749, in Fifeshire, and was the eldest son of Major Pitcairn, who was killed at the battle of Bunker’s-hill, where he commanded a corps of marines. He received his preliminary education at the High school of Edinburgh, when he was removed to the college of Glasgow, where he continued some years in attendance on the general classes. He next revisited Edinburgh, attended lectures in the college there, and in 1773 was sent by his uncle, Dr. William Pitcairn, president of the College of Physicians, to Corpus Christi college, Cambridge, as a member of which house he proceeded M.B. 1779; M.D. 1784. He settled in London as soon as he had taken his bachelor’s degree; and on the 10th February, 1780, was elected physician to St. Bartholomew’s hospital. Dr. David Pitcairn was admitted a Candidate of the College of Physicians 9th August, 1784; and a Fellow, 15th August, 1785. He was Censor in 1785, 1786, 1791, 1796, 1806; Gulstonian lecturer and Harveian orator in 1786; and Elect, 11th March, 1806. "The success of Dr. Pitcairn in practice (writes Dr. Macmichael) was great; and though one or two other physicians might possibly derive more pecuniary emolument than himself, certainly no one was so frequently requested by his brethren to afford his aid in cases of difficulty. He was perfectly candid in his opinions, and very frank in acknowledging the extent of his confidence in the efficacy of medicine. To a young friend who had very recently graduated, and who had accompanied him from London to visit a lady ill of consumption in the country, and who, on their return, was expressing his surprise at the apparent inertness of the prescription, which had been left behind (which was nothing more than infusion of roses with a little additional mineral acid), he made this reply: 'The last thing a physician learns, in the course of his experience, is to know when to do nothing, but quietly to wait and allow nature and time to have fair play in checking the progress of disease and gradually restoring the strength and health of the patient.’ His manner was simple, gentle, and dignified; from his kindness of heart he was frequently led to give more attention to his patients than could well be demanded from a physician; and as this evidently sprung from no interested motive, he often acquired considerable influence over those whom he had attended during sickness. No medical man, indeed, of his eminence in London, perhaps, ever exercised his profession to such a degree gratuitously. Besides, few persons ever gained so extensive an acquaintance with the various orders of society. He associated much with gentlemen of the law, had a taste for the fine arts, and his employment as a physician to the largest hospital in the kingdom made known to him a very great number of persons of every rank and description in life. His person was tall and erect; his countenance during youth was a model of manly beauty; and even in advanced life he was accounted remarkably handsome. But the prosperous views that all these combined advantages might reasonably open to him were not of long endurance.

Ill health obliged him to give up his profession, and quit his native country. He embarked for Lisbon in the summer of 1798, where a stay of eighteen months in the mild climate of Portugal, during which period there was no recurrence of the spitting of blood with which he had been affected, emboldened him to return to England, and for a few years more resume the practice of his profession. But his health continued delicate and precarious; and in the spring of the year 1809 he fell a victim to a disease that had hitherto escaped the observation of medical men. Pitcairn, though he had acquired great practical knowledge, and had made many original observations upon the history and treatment of diseases, never published anything himself; but the peculiar and melancholy privilege was reserved for him to enlighten his profession in the very act of dying.

On the 13th of April he complained of a soreness in his throat; which, however, he thought so lightly of that he continued his professional visits during that and the two following days. In the night of the 15th his throat became worse, in consequence of which he was copiously bled at his own desire, and had a large blister applied over his throat. On the evening of the 16th Dr. Baillie called upon him accidentally, not having been apprised of his illness; and, indeed, even then observed no symptom that indicated danger. But the disease advanced in the course of that night, and a number of leeches were applied to the throat early in the morning. At eleven o’clock in the forenoon Dr. Baillie again saw him. His countenance was now sunk, his pulse feeble and unequal, his breathing laborious, and his voice nearly gone. In this lamentable state he wrote upon a piece of paper that he conceived his windpipe to be the principal seat of his complaint, and that this was the croup. The tonsils were punctured, some blood obtained, and a little relief appeared to have been derived from the operation. Between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, his situation seemed considerably improved, but soon afterwards a slight drowsiness came on. At eight, the patient's breathing became suddenly more difficult, and in a few minutes he was dead. This was the first case of this peculiar affection of the throat that has been distinctly recognised and described. It was an inflammation of the larynx, or upper part of the windpipe, of so insidious a nature as hitherto to have passed unnoticed."(1) Dying on the 17th of April, 1809, in Craig’s-court, Charing-cross, he was buried at St. Bartholomew’s-the-less, in the same vault with his father, Major Pitcairn, whose remains had been brought from Bunker’s-hill, and his uncle, William Pitcairn, M.D. Dr. Pitcairn (2) is commemorated by a mural tablet in the church of Hadham Magna, co. Herts, which bears the following brief inscription:—

To the memory of David Pitcairn, M.D., F.R.S., S.A., who departed this life April 17th, 1820, aged fifty-nine years.

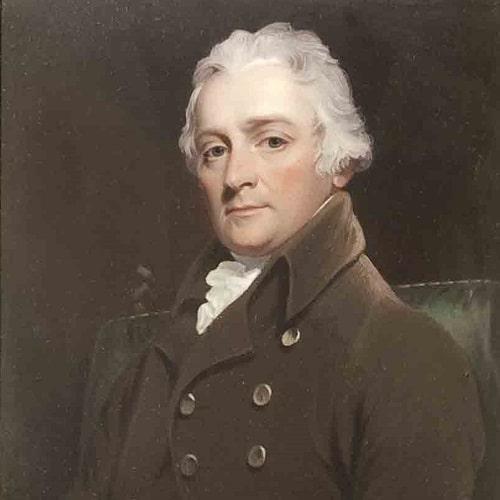

An excellent portrait of Dr. Pitcairn, by Hoppner, is in the College.(3) It was engraved by Bragg.

William Munk

[(1) The Gold-Headed Cane. 2nd ed. 8vo. Lond. 1828, p. 230.

(2) Pitcairnus de patria bene meritus est, qui valetudinario sancti Bartholomæi plures annos singulari laude præfuit: in quo pauperes pene innumerabiles cura sublevavit, multosque discipulos, præceptis ex re natis, ad medicinam faciendam optimè instituit. Nam fuit in illo gravitas et autoritas, quanta magistrum decet; simul gratia et probitas, quibus discentium animos mire ad se allexit. Postea, relictis publicis muneribus, cum ad privata totum se converterat, inter summi ordinis ægros occupatissimus vixit, donec adversa valetudo, ut sibi caveret, monuisset. Tunc sine mora Ulyssipponem se subduxit, ubi otium perinde ac salutem reciperet. Inde ut rediit, paucos modo curare constituit, neque, ut ante, mediis negotiorum fluctibus si implicari sivit. Medicinam tamen adhuc exercebat, crescente etiam ætate vegetior factus, cum hominem temperantem, summum medicum, tantus improviso morbus oppresserit, ut præclusis inflammatione et tumore faucibus, vix diem unum atque alterum superesset. Lugeamus, amici, sortem humanum! lugeamus socios amissos! vel potius eorum sic meminerimus, ut quoties cunque de clarissmis et beatissimis viris cogitemus, nosmetipsos ad virtutem accendere, et ad omnem fortunam paratiores praestare videamur. Oratio Harveiana habita die Octobris xviii, A.D. MDCCCIX, a Gulielmo Heberden. p. 23.

(3) The portrait was bequeathed to the College by Elizabeth, the widow of Dr. David Pitcairn, and only daughter of William Al-mack, esq., by her will, dated 11th August, 1837:—" I give and bequeath to the Royal College of Physicians in London the portrait of my beloved husband, Dr. David Pitcairn, painted by Hoppner; and also the portrait of Dr. William Pitcairn, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and also the portrait of Dr. Matthew Baillie, painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence. I give and bequeath to Sir Ralph An-struther, bart., my picture of his great-grandfather, Dr. Archibald Pitcairn, painted by Sir John Medina. I give to his brother, Hamilton Lloyd Anstruther, esq., my little silver cup with the Greek motto, that was his great-grandfather’s, Dr. Archibald Pitcairn." In 1844 a request was made by Sir John Campbell that the portraits above-mentioned might be allowed to remain in the possession of the relatives and legal representatives of the deceased, but the College resolved that an answer should be returned to the effect that—" The President and Fellows do not feel themselves entitled to alienate from the College the portraits of three of its most highly-esteemed fellows, which had been bequeathed in so kind a manner to the College]