Under the skin: illustrating the body

Under the skin: illustrating the body

Anatomical illustrations of the human body are as diverse as the people they represent, and the people who make them.

There are many ways to translate the three-dimensional human body into two-dimensional forms, in drawings, books or on computer screens. The human body is vastly complex, and illustrators must make choices about what to show and in how much detail.

The images in this exhibition were created to inform, instruct and – in some cases – entertain. Used primarily for research, training, education and treatment by students and medical specialists, they were also highly desirable to collectors, connoisseurs and the non-specialist public.

As works of art, the illustrations reflect changes in artistic style, technology, methodology and purpose, and the evolution of medical theory and practice over the centuries.

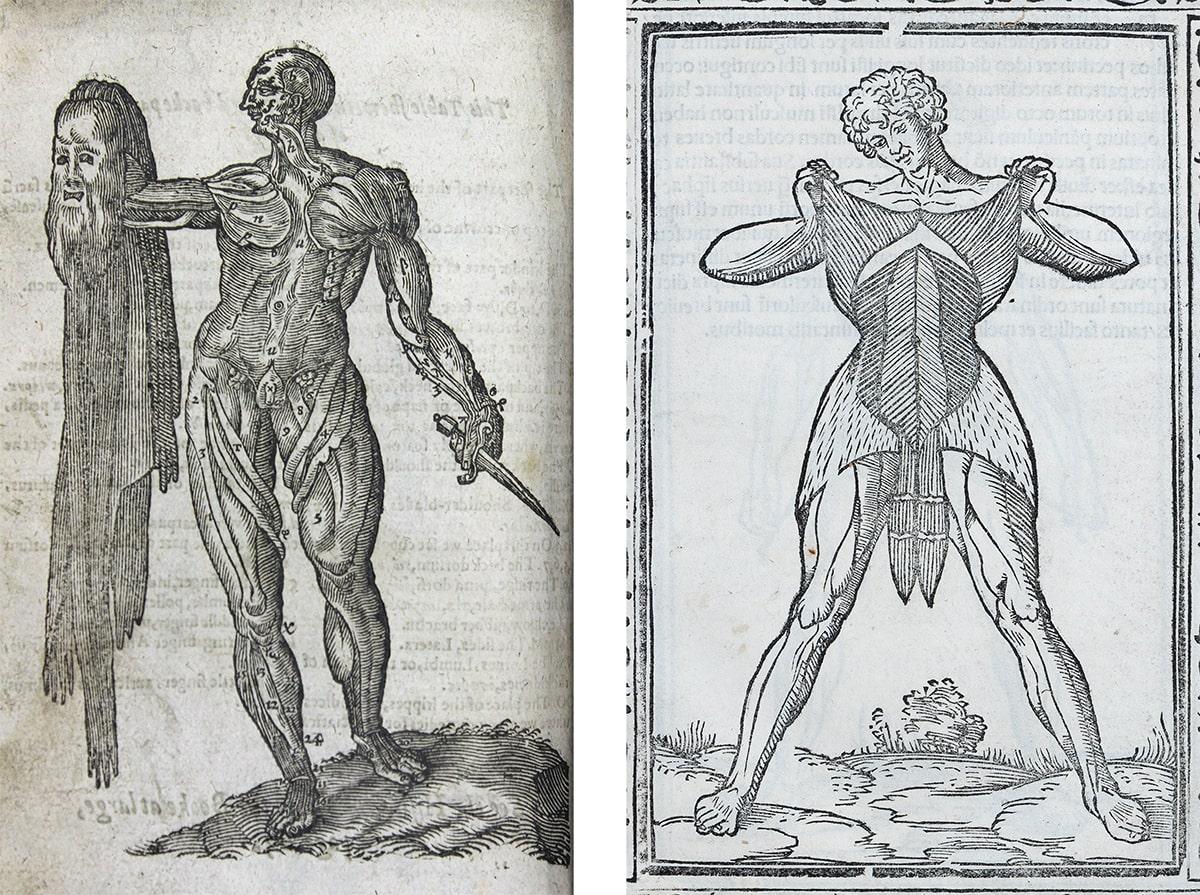

Woodcut illustrations of the musculature

LEFT: The flayed body, in Sōmatographia anthrōpinē. Or, A description of the body of man. Text by Helkiah Crooke, abridged by Alexander Read, published London, 1616.

A flayed man stands as if still alive, holding up his own skin, the features of his face still clearly visible on the ghost-like surface. This unsettling image is common in anatomy books from the 16th and 17th centuries. It shows the visceral reality of how anatomy was taught and learned at the time – through dissection. It also appears comic because of its absurdity, and it very clearly illustrates the practice of looking ‘under the skin’.

RIGHT: Layers of abdominal muscles, in Isagogae breves per lucide ac uberrime in anatomiam humani corporis. Jacopo Berengario da Carpi, published Bologna, 1523.

Simple parallel lines in these woodcuts are surprisingly effective at showing the texture and shapes of muscles, which are revealed as the figure lifts his own skin.

View the catalogue record for Sōmatographia anthrōpinē or View the catalogue record for Isagogae breves.

Heart. Angela Palmer, 2017

Heart. Angela Palmer, 2017.

Angela Palmer has recreated a human heart as a three-dimensional drawing. It appears to float in space, coming in and out of view as you move around it.

Palmer used a series of magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of a preserved human heart. Line drawings derived from 18 separate cross-sections were engraved and inked onto sheets of clear glass. Palmer wanted to use MRIs of a living heart to create this work, but the constant movement of the heart created blurred images.

The sculpture was created in collaboration with Professor Paul Laizzo at the Visible Heart Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, USA. The RCP Museum commissioned this work as part of the 500th anniversary of the RCP in 2018, inspired by William Harvey’s pioneering work on the circulation of blood.

De humani corporis fabrica, 1543

Muscles of the male human body (front) in De humani corporis fabrica. Text and dissection by Andreas Vesalius, drawing attributed to Jan Sephan van Calcar, woodcuts by unknown artist, published Basel, 1543.

Vesalius' 1543 book De humani corporis fabrica ('On the fabric of the human body') is famous for the quality and accuracy of its anatomical images. It includes striking woodcut illustrations of flayed bodies standing in Italian landscapes.

Remarkably, several of the pictures were designed with a continuous background so that they can be joined together to make a panorama. These illustrations are not next to each other in the book itself. They are separated by pages of text, so the panorama only becomes visible using a reconstruction.

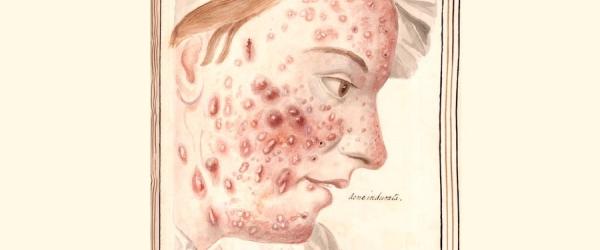

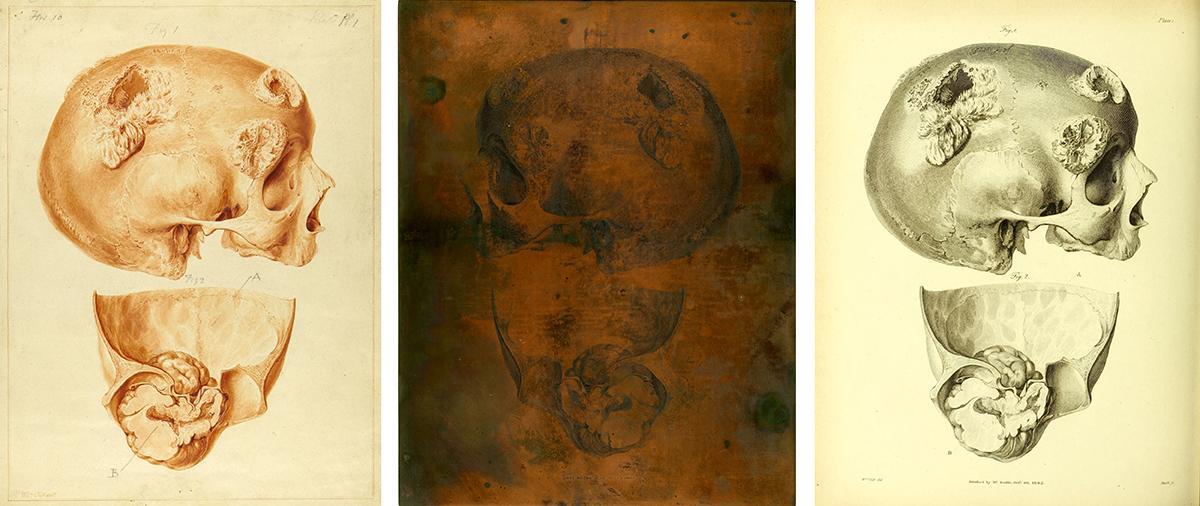

Two diseases of the skull dissected by Matthew Baillie

LEFT: Chalk and watercolour drawings by William Clift, 1793.

Physician Matthew Baillie (1761–1823) employed artist William Clift to draw his dissected specimens in watercolour. This was the first stage in translating Baillie’s dissections of bodies on to the two-dimensional printed page.

CENTRE: Engraved copperplate by James Basire II, 1799–1802.

Clift’s drawings were engraved onto copperplates by James Basire II. The image is reversed on the plate so that it appears the right way round when printed.

RIGHT: Printed illustration in A series of engravings … intended to illustrate the morbid anatomy of some of the most important parts of the human body, published London, 1799–1802.

Different printing techniques use different methods to produce three-dimensional effects. Fine lines and hatched areas create texture and tone in engravings. However, a smooth gradation of tone is not possible, and some of the textural effects in Clift’s drawings do not appear in the final printed version.

Explore Baillie's complete Series of engravings … online:

View the catalogue records for the drawings, engraved copperplates, and book.

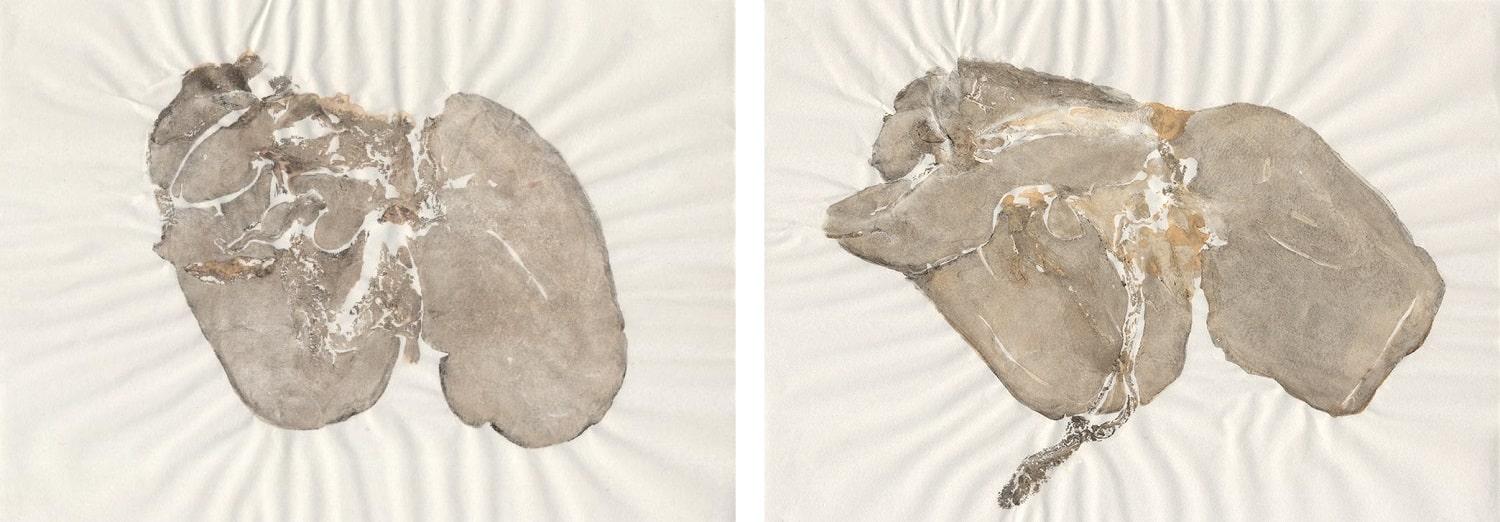

Liver models

Liver models. Amanda Couch, nature print on paper, 2016.

Amanda Couch makes these nature prints by applying black ink directly to the surface of fresh lamb livers, then placing paper directly on top of them. The prints clearly show the textures and shapes of the individual organs, but the artist has little control over the appearance of the finishd work.

Traditional anatomical illustrations do not necessarily represent a single moment of dissection. They are the result of a process in which the artist has made choices about which features to include or omit. By contrast, Couch’s prints make visible every part of the liver that the paper touched, creating a variety of evocative images, which do not have the rigorous clarity required in formal medical illustration.

Extispicy in the everyday with artist Amanda Couch

Join artist Amanda Couch for an exploration of human-environment binaries through the gut. The workshop draws on Amanda’s artwork and research into the ancient practice of extispicy – divination using the entrails.

Recording of a digital workshop held on 19 September 2020.

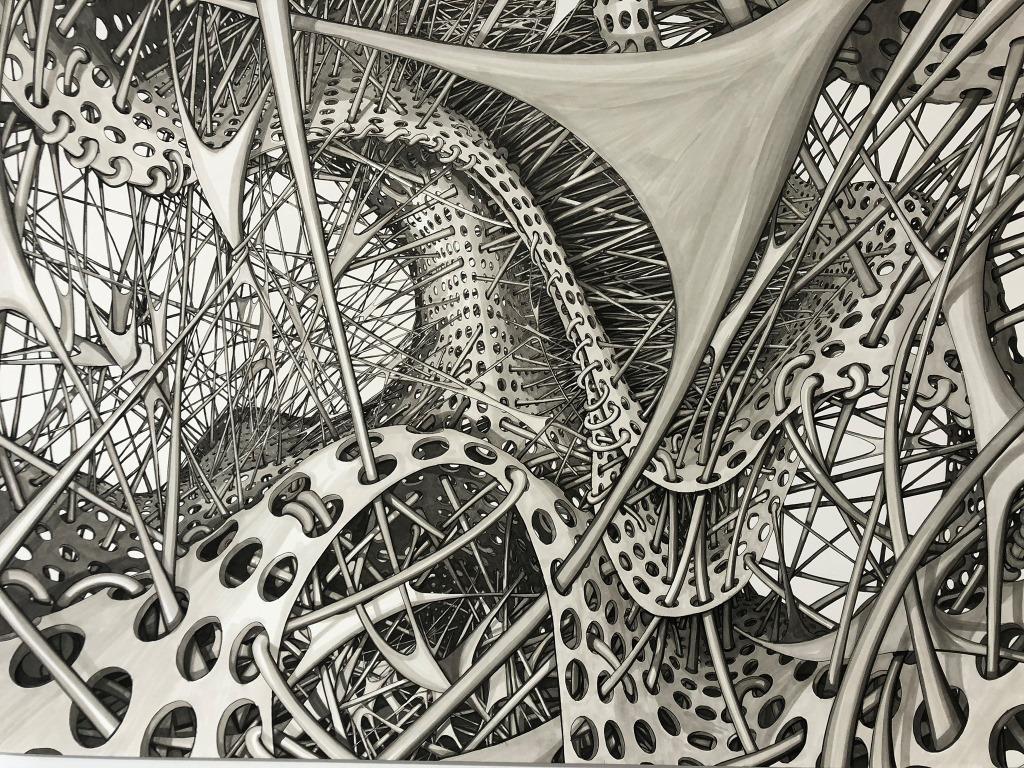

Stem 006. Ruth Uglow, pen and Copic markers, 2014.

The structures in this picture appear to be moving and growing before our eyes. Ruth Uglow wanted the image to draw viewers right inside its ‘micro-architectural framework’.

The highly detailed drawing shows an imaginary microscopic anatomy, inspired by views down a microscope of stem cells growing on artificial scaffolding material. Modern anatomical research takes place at a microscopic level far removed from the dissections and studies represented elsewhere in the exhibition.

This work is part of a series of drawings commissioned by the Royal Free Hospital for its new Institute of Immunity and Transplantation.

Part of the exhibition 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity'. Explore further: