Catch your breath: audio extracts

Below you will find audio extracts from the 'Catch your breath' exhibition

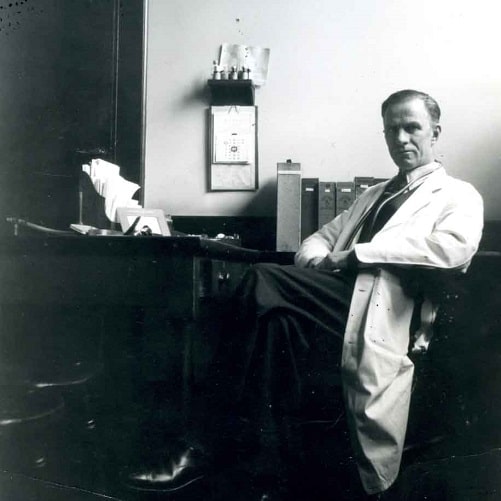

Bill Frankland talks about treating Saddam Hussein for smoking related asthma

Bill Frankland: Transcript

Bill Frankland talks about treating Saddam Hussein for smoking related asthma

I was doing out-patients and they said would I answer the phone and I said, 'No, you know I never answer the phone when I'm seeing patients,' and I think I had students at the time, and they said, 'Oh, it's an embassy!' so I said, 'Oh, well, I'll go,' and they said would I go out that weekend to see a VIP, and I said, 'What country?' and so on and then I learned, Baghdad, which I knew nothing about. So I went out. And to be going out and seeing Saddam Hussein, who'd been in power by that time five or six months. And he was being treated as an asthmatic. But Saddam Hussein, when I was taking the history, to me he was very interesting.

He understood English but wouldn't talk English so it was done through an interpreter, but that didn't matter, but if he wasn't sleeping praying or eating he was smoking a cigarette. So that was 40 plus a day and that was his problem. And I knew nothing about the man and I told him he was a patient and I treated him like anyone else, although he was head of the state, I said, 'To me you are a patient,' and I said, 'I treat you in the same way as I treat a beggar.' I told him he had to stop smoking but as he was so addicted to it I didn't know that he would stop smoking. But foolishly I said, 'If you go on smoking you know you're getting worse all the time your chest is getting worse and worse and that's entirely due to the smoking. And', I said, 'I can't imagine that you will be head of the state in two years’ time because of your habit.' 'When are you coming to see me again?' I said, 'I'm not. I have one rule in life and I like to help my patients, and if you go on smoking I know you're going to get worse and the rule is', and I said to him face to face, 'whether you are head of the state or a beggar, it makes no difference to me', I said, 'I want to help my patients, I know you will get worse, that's why I will not come and see you again, I refuse.' And he was a bit worried about this, and he looked worried at the time.

That was in the, yes, the afternoon. But when I was waiting in the airport, VIP lounge, the first time it had ever been used, it was a new airport, or a new building, a little man came along and said, 'Someone that you are interested in has done what you wanted him to do, and he wants to know when do you want to come and see him again?' So he got the message, Saddam Hussein got my message, and in fact he did stop smoking.

Margaret Turner-Warwick recalls working on the triple treatment for TB having contracted the disease herself as a medical student

Margaret Turner-Warwick: Transcript

Margaret Turner-Warwick recalls working on the triple treatment for TB having contracted the disease herself as a medical student

And I went to the Brompton. I may tell you that I took three goes in getting a house job at the Brompton. I failed twice, so it’s not all swimming, but I stuck to it and got there. And then I became very interested in the opportunities for chest medicine, but of course, it was just undergoing this fabulous revolution because of treatment of tuberculosis…. ’47 it [streptomycin] was flown over from the States for one or two people. And when I was in Switzerland, I remember one of the first people who had been treated with [streptomycin].

I was also involved in the first MRC trail, I think, in, it must have been 1952, when isoniazid was introduced in combination with streptomycin, combination therapy, for one whole month. And we were fascinated by the patients; their temperatures came down, their sedimentation rates improved, they felt marvelously better. And at the end of the month of course they stopped, because a month’s treatment was a long time at that time – and they all relapsed. And the people who were running this trial said, ‘You know, that’s nearly the right drug, but it’s never going to take on because, of course, they relapse when you stop it.’…

And I remember so well how, at the coal face, that trial so easily might, you know, have given quite the wrong message unless somebody said, ‘Why stop?’ And of course, again, I’m not sure that everybody would agree with this, but in my experience one of the people who said so strongly, ‘Why stop?’ was [John] Clifford Hoyle. And he indeed wrote a paper with Howard Nicholson and John Batten and myself – John and I were the sort of stooges on this paper – which was his experience of treating people with combination PAS [para-amino salicylic acid] isoniazid and streptomycin, for a whole eighteen months. It was heavily criticized because it was uncontrolled, but that was the way that he established writing up his experience, and of course, I think that was certainly one of the very early thinkings behind you needed eighteen months to two years treatment.

Stephen Spiro explores the difficulties of raising funds for lung related illnesses

Stephen Spiro: Transcript

Stephen Spiro explores the difficulties of raising funds for lung related illnesses

Smoking has been a huge part of my life in that most of the diseases I’ve been involved in.. are smoking related. And, I’ve been a trustee of the British Lung Foundation since 2004. I was president of the British Thoracic Society in 2003 I think it was and in my key note address I--, I highlighted the huge deficit in charitable funding for respiratory diseases. I mean we are really a Cinderella specialty in terms of its importance and its funding and it’s always frustrated me in that the British Lung Foundation, which is a super organisation, and respiratory disease is a quarter of all acute medical problems, huge problem worldwide, and yet we bring in about six and a half million pounds a year as a charity. The British Heart Foundation probably a couple of hundred million and heart disease is no more prevalent than lung disease. And it’s always upset me and stressed me as to why we don’t get more money and why we can’t raise more money. And I think it’s because lung disease is not a single charity. If you’re Parkinson’s or muscular dystrophy it’s clearly defined. Lung disease is 30 or 40 or 50 different diseases. A lot of it is smoking related, a lot of it therefore is in people who are poorer or of lower

social class and it just doesn’t resonate ….We talk endlessly how we can become a ten million pound charity and we’re not short of enthusiasm or ideas and as an organisation, as a charitable organisation, we punch way above our weight politically. We’ve just had parliament pass a year ago that there should be no smoking in cars with children, adults shouldn’t smoke so the kids don’t get exposed to passive smoking. We’re doing a huge amount of money raising for research in asbestos related diseases, we do a lot in lung cancer, a lot in COPD, but raising money is so hard.

John Turner (centre) and David Young talk about pollution in Manchester and Sheffield in the 1940s and 1950s and the prevalence of people with respiratory problems

John Turner and David Young: Transcript

John Turner (centre) and David Young talk about pollution in Manchester and Sheffield in the 1940s and 1950s and the prevalence of people with respiratory problems

John Turner: So I walked …down to the Don Valley, and as you got down there you could see the flares from the chimneys, the huge pall of black smoke over the city. We lived up on a hill, our road was called Sky Edge Road [laughs] and we were right up on top of the hill, you looked down and you really couldn’t see the city, usually, on most days, just covered in this black pall of smoke. So we got down to the Hallamshire steelworks, went in and most of the men were stripped to the waist, covered in coal dust and sweat, and you see these huge rolling mills, strip metal coming off, molten metal coming off the rolling mills, big crucibles of molten metal being lifted and turned…..you know, nobody with ear protection, nobody with mask or respiratory protection, and you could see the working conditions there, you know, Dante’s Inferno.

David Young: Yes, I think chronic respiratory diseases, what was called in those days chronic bronchitis and emphysema, these days we would call it something like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, I think it's fair to say that was probably the condition that appeared most prominently. I experienced a Manchester fog, you know, the real old-fashioned pea-soupers, maybe two or three times within a year. The old pea-soupers were, literally, you couldn't see your hand in front of your face. I remember sitting in a bus driving up Oxford Road, from Rusholme to wherever the university was and looking out of the window and hardly being able to see anything. And another time driving a car following the road and turning a corner and ended up in somebody's drive because I thought the road had turned but it was somebody's drive. And the buses being taken off the roads because visibility was maybe ten or twenty yards. Fortunately that only happened once or twice and, you know, there was the Clean Air Act and so fossilised fuel fires were going out so the whole situation was getting better. So, yes, chronic respiratory disease I would say is the thing that was most evident.

Linda Luxon talks about looking after patients who had spent many years in Iron Lungs

Linda Luxon: Transcript

Linda Luxon talks about looking after patients who had spent many years in Iron Lungs

Well, they were in an iron lung to assist their breathing and many of them had to be fed. The doctors were actually making sure that they didn't get infections, checking that their oxygen levels were fine, so it was more of a matter of keeping them safely alive. I mean I don't, I just don't remember them being out of those iron lungs at all. I'm sure some of them must have been but I don't remember that. It was, I mean, it really was very sad. And lots of the patients were very depressed. Well I don't know what the overall prognosis was. I mean, I don't remember anybody dying in the short time I was there, but I was only there two or three months and some of these people had been there certainly for five, ten years. Yes, it was awful, it was grim.

David Young remembers TB wards before they were emptied by the triple treatment

David Young: Transcript

David Young remembers TB wards before they were emptied by the triple treatment

Now Bagley had been a TB sanatorium. The treatment for tuberculosis before active treatment was fresh air and rest. So hospitals were built out in the country to give access to fresh air, and if you were really wealthy you went off to Switzerland. So I went to Bagley. By this time it was a chest hospital - a lot of chest problems in Manchester you know, air pollution, smoking, poor community, a lot of poverty and ill health so a lot of that kind of patients. When I was a student, when we were all students, we visited Bagley as a chest hospital. And they took us to something they called the Horse Boxes. Now the Horse Boxes were a single storey ward on its own and it was divided into rooms, a window on either side of the room and a door on either side of the room and it was a stable door. They were half doors; you could open the top and open the bottom, or whatever. And the patients were in the beds, there were two patients in each room, in their overcoats and mufflers and hats, and the stable door, the top halves were open, and it was the fresh air business. And that was in the - would be in the early 60s. Anyway, by the time I got to Bagley about three, four years later these were all gone.