Stonehenge has been an enigmatic presence on Salisbury Plain for millennia, but it wasn’t until the 17th century that antiquarians, gentlemen historians and an early breed of ‘scientists’ began to debate its possible origins.

In 1663, the royal physician Walter Charleton published Chorea gigantum [giants’ dance]: or, The most famous antiquity of Great Britain, vulgarly called Stone-heng, standing on Salisbury-Plain, restored to the Danes, arguing that the monument was the work of the Vikings. It’s one of the more surprising books in the heritage library. A presentation copy was given to his patron, King Charles II.

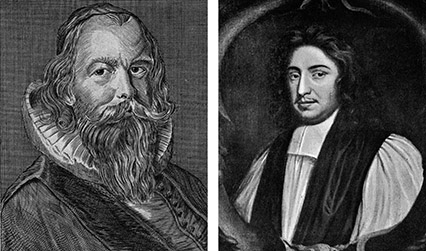

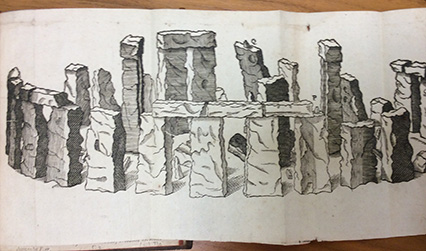

Charles’ grandfather, James I, had become aware of the stones in 1620 when he stayed at nearby Wilton House, and had asked his royal surveyor, Inigo Jones, to investigate the monument. Jones’ report, published posthumously in 1655, argued that Stonehenge was of Roman origin and specifically Tuscan in style. Jones, who had visited Italy and had seen Roman remains for himself, came to the surprising (and frankly circular) conclusion that, as a ‘magnificent monument’, Stonehenge must have been built by the Romans, since theirs was the only culture that had occupied England capable of creating such magnificence.

Chorea gigantum was Charleton’s response to Jones’ Roman claim. The first half of the book compares Jones’ description of the ruin to the findings of William Camden, the distinguished antiquarian and topographer, who surveyed the site for his book Britannia. Charleton sides with Camden, noting that

having more than once or twice delighted my self with viewing this admirable Antiquity, and with all possible attentiveness of Mind contemplated the Form, Order and Parts of it; I always observed Mr Camden’s Draught to come much nearer in Resemblance.

Charleton then systematically compares the monument to the ‘many Stupendous Piles of Stones’ in Denmark described by the Danish Royal physician Ole Worm in Danicorum monmentorum (1643). Charleton concludes that Stonehenge must have been the work of the Danes, since they had the technology and skill to transport and elevate the monolithic stones, and that the monument was built as a meeting place for the election and coronation of the Danish kings.

Walter Charleton was at the centre of the 17th century revolution in science. The son of a rector from Somerset, he was educated at Oxford, where he was taught by the influential natural philosopher, John Wilkins. It was at Wilkins’ Oxford lodgings that the Experimental Philosophical Clubbe, a precursor of the Royal Society, regularly met during this period, a forum where influential figures including Christopher Wren, RCP fellow Thomas Willis and Ralph Bathurst met and discussed science, ideas and experimentation. In 1643 Charleton, then only in his early twenties, was made a physician in ordinary to Charles I, then residing in Oxford during the Civil War. In this role, he presumably came into contact with the great William Harvey, who, as senior Royal physician, would also have been in attendance on the king.

After leaving Oxford and following Charles I’s execution in 1649, Charleton moved to London, where he set up a practice as a physician in Russell Street, Covent Garden. He became a candidate of the College of Physicians in April 1650 (becoming an honorary fellow in 1664, a fellow in 1676 and president in 1689) and, having maintained his allegiance to the Royalist cause, was made physician in ordinary to the exiled Charles II. In 1663, following the Restoration, he became a fellow of the newly-established Royal Society. Here he was active in debates and a keen experimenter: he was the first to show that tadpoles become frogs, and that the speed of sound changes according to differences in humidity and temperature during the day and night. During this period, he also wrote a number of medical texts, including Exercitationes pathologicae (1661) and the first physiology textbook in English Natural history of nutrition, life, and voluntary motion (1659).

Despite these links with the ‘new science’, the Royal Society and contemporary ideas, Charleton was actually a more ambiguous figure. As Emily Booth has shown in her study of Charleton, he was eclectic in his approach, using a mix of ideas and philosophies, old and new. As well as medical texts, for example, he wrote and translated several religious and philosophical books, including some of the first works in English on Epicureanism. Charleton was from a modest background, had no independent income and made his living as a working physician, relying on attracting and retaining patients. His eclecticism may have been based on pragmatism, allowing him

to maintain the links with the traditional bases upon which medical practice was founded, and also to demonstrate an awareness of recent innovations and discourses, protecting himself against criticisms of “dogmatism”.

Chorea gigantum demonstrates Charleton’s mix of ‘new science’ and more established approaches to knowledge. The book is ‘scientific’ in the sense that he distances himself mythological interpretations of the monument, arguing ‘the Fable of Merlin’s Transportation of it out of Ireland is absurd and ridiculous’. He is also systematic in his analysis of the various features of Danish sites and Stonehenge, even providing a helpful table of comparison. But, he resorts to the classical tradition of using logic to outline his theory (he points out that ‘no one hath so much as mentioned Stone-Heng, until a long time after the Danes had conquered England’) and by resorting to older, established authorities (Jones, Camden and Worm), rather than using facts gathered from his own observations.

Chorea gigantum is probably best understood as a political or – frankly – sycophantic work. The copy Charleton gave to his patron, Charles II, was bound in red morocco leather, embossed with a double crowned ‘C’ and included a poem by the eminent poet John Dryden. Charleton would have known that Stonehenge had a particular significance for Charles: while on the run, having fled the Battle of Worcester in 1651, Charles had stayed at Heale House in Wiltshire and had spent a day at nearby Stonehenge. After the Restoration, his six-week epic escape across England to the coast took on a near mythological significance for the king and his followers. Charles was no doubt delighted to be reminded of his thrilling flight.

Charleton might have also intended to give a more subtle political message to the king. Stonehenge was according to Charleton, after all the place where the Danes elected their kings. Charleton may have been attempting to contribute to the ongoing, contemporary debate about the extent of the power of the king.

Sarah Gillam, assistant editor, Munk's Roll

The following sources were used when writing this post:

- Booth E. ‘A subtle and mysterious machine’ The medical world of Walter Charleton (1619-1707). Dordrecht: Springer, 2005.

- Fraser A. King Charles II. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979.

- Hill R. Stonehenge: wonders of the world. London: Profile Books Ltd, 2008.

- Jones I, Charleton W, Webb J. The most notable antiquity of Great Britain, called Stone-heng…restored. [2nd edition]; added, The Chorea gigantum; or Stone-heng restored to the Danes, by Dr Charleton; and Mr Webb’s Vindication of Stone-heng restored… London: D Browne, 1725.

- Kargon R. Encyclopedia.com. Charleton, Walter. https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/medicine/medicine-biographies/walter-charleton [Accessed 12 March 2018].

- Moore N. Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 10. Charleton, Walter. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Charleton,_Walter_(DNB00) [Accessed 12 March 2018].

- Munk W. The Royal College of Physicians. Lives of the Fellows. Walter Charleton http://munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk/Biography/Details/824 [Accessed 12 March 2018].

- Rolleston H. Walter Charleton, DM, FRCP, FRS. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol.8, No.3, March, 1940, pp.403-16.

- Winterbottom A. London blog: the elusive legacy of Walter Charleton. Nature.com http://blogs.nature.com/london/2007/04/24/the-elusive-legacy-of-walter-charleton [Accessed 12 March 2018].