Training to be a rare book and special collections librarian is a thrilling ride, sometimes you can’t help but feel like a detective or historian trying to crack the case; though the ‘case’ in question, is trying to piece together a history of book ownership. One can quite spend hours trying to crack the code of provenance, and I mean that literally after looking at 17th century shorthand (check out the RCP museum twitter, if you want to give it a go).

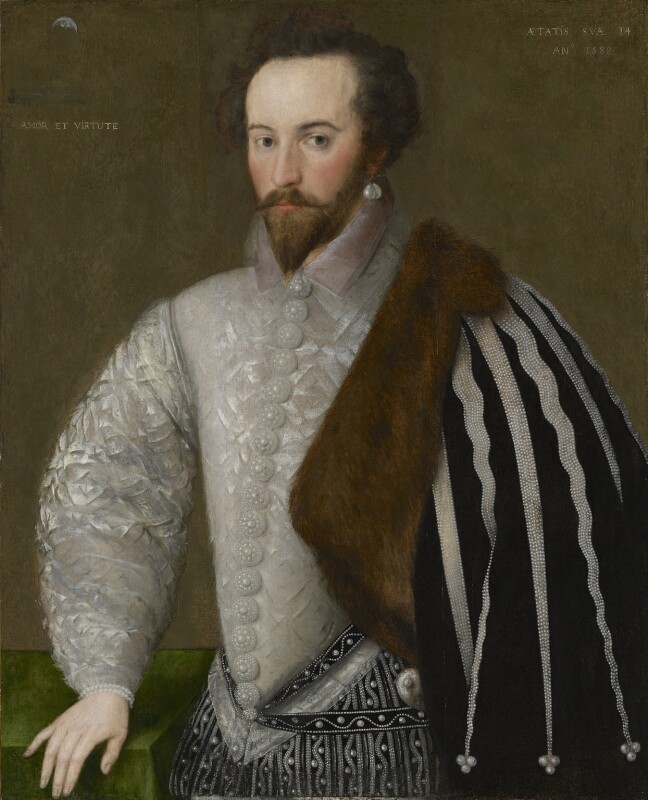

However, through my work experience, a true treasure trove of study has come from these 17th century medical books, not only for their provenance but the window into the medical culture of the time they provide. The great physicians of the 16th and 17th centuries were diverse and complex people, with their interests covering far more than what is considered within the realm of medical pursuits today. The book that I wish to draw attention to arguably defines the period’s relationship with medicine and its close companionship with alchemical pursuits. Though what makes this piece all the more interesting is the man and the myth behind it, the notorious Sir Walter Raleigh (1552–1618).

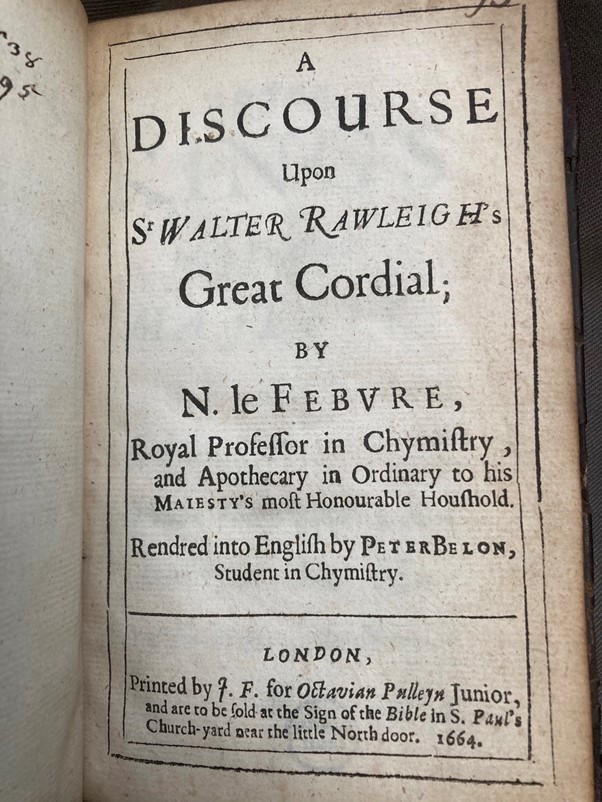

A quick note on the book in question: it’s the 1664 publication A discourse upon Sir Walter Raleigh’s great cordial by French physician and apothecary to Charles II, Nicaise Le Fèvre. This edition is especially notable for the RCP collection, as it is the first edition translated into English of Le Fèvre’s depiction (and really our only source) of the cordial, listing in rather extreme detail, the extensive list of ingredients that made up Raleigh’s alchemical magnum opus.

Known more for being the ‘favourite’ of Queen Elizabeth I, Raleigh often found himself in the spotlight for his relationship with the queen and the many exploits he pursued while under her patronage, including several voyages as a coloniser to the so-called ‘New World’. This included Raleigh overseeing (from England) in 1585 the settlement, in what is now North Carolina, of one of the first American colonies, the colony of Roanoke; which is embroiled in its own mysteries as the infamous ‘Lost Colony’.

Raleigh was given a seven-year charter to colonise the West and it was during this time he became fascinated by the legends of the golden city of El Dorado. Though his voyages to discover this mythic city would always end in failure, these journeys west bought Raleigh’s attention to the plethora of new botany and medical ingredients previously unfamiliar to the English. Though, most famously bringing back potatoes and tobacco, Raleigh also bought back other fauna and flora which would be the base and tools of his exploration into the field of alchemy.

Raleigh’s life seemed to be followed by incredible rises and then dramatic falls, losing favour with royals as quickly as he had gained it. This was especially the case following the death of Elizabeth I and the following succession of James VI and I, who Raleigh had a contemptuous relationship with. Almost immediately upon James’ succession, Raleigh was arrested again and taken back to the Tower of London, for his second and longest stay of thirteen years (1603–1616). It was during this time however, that Raleigh began experimenting and exploring the properties of the new ingredients he bought back from the Americas. Propagating an impressive medicinal or early physic garden within the Tower of London, which he used in his alchemical pursuits, making poultices, tonics, and cordials. Raleigh’s reputation as a reputable alchemist was growing, with him providing medicinal assistance to members of the royal family (including Queen Anne). However, out of all of Raleigh’s alchemical experiments, it is his ‘great cordial’ that lived on with his legacy as the ultimate ‘incomparable remedy’.

Raleigh’s great cordial contains over forty ingredients, designated into three categories based upon a hierarchy of ‘nobleness and excellency’: starting with animal life: then vegetable life: and finally mineral life. Some exceptional ingredients from the extensive list include the bezoar, the calcified gallstone of an animal commonly thought as an antidote to poisoning (potentially useful to the tumultuous courts of 17th century Europe); the flesh, heart and liver from a viper, which is added for its effectiveness against poisons but more importantly the plague; some more recognisable flowers/plants including saffron, marigold, elderflowers and the rose. The rose receives particular emphasis as the ‘queen of flowers’ and for being integral to the form and consistency of the cordial, commonly believed to benefit the heart, spirits and cleansing of wounds. Before the discovery of germ culture, illness was still linked to miasmas and foul smells, so it follows suit to include flowers with heavy floral scents as common cures.

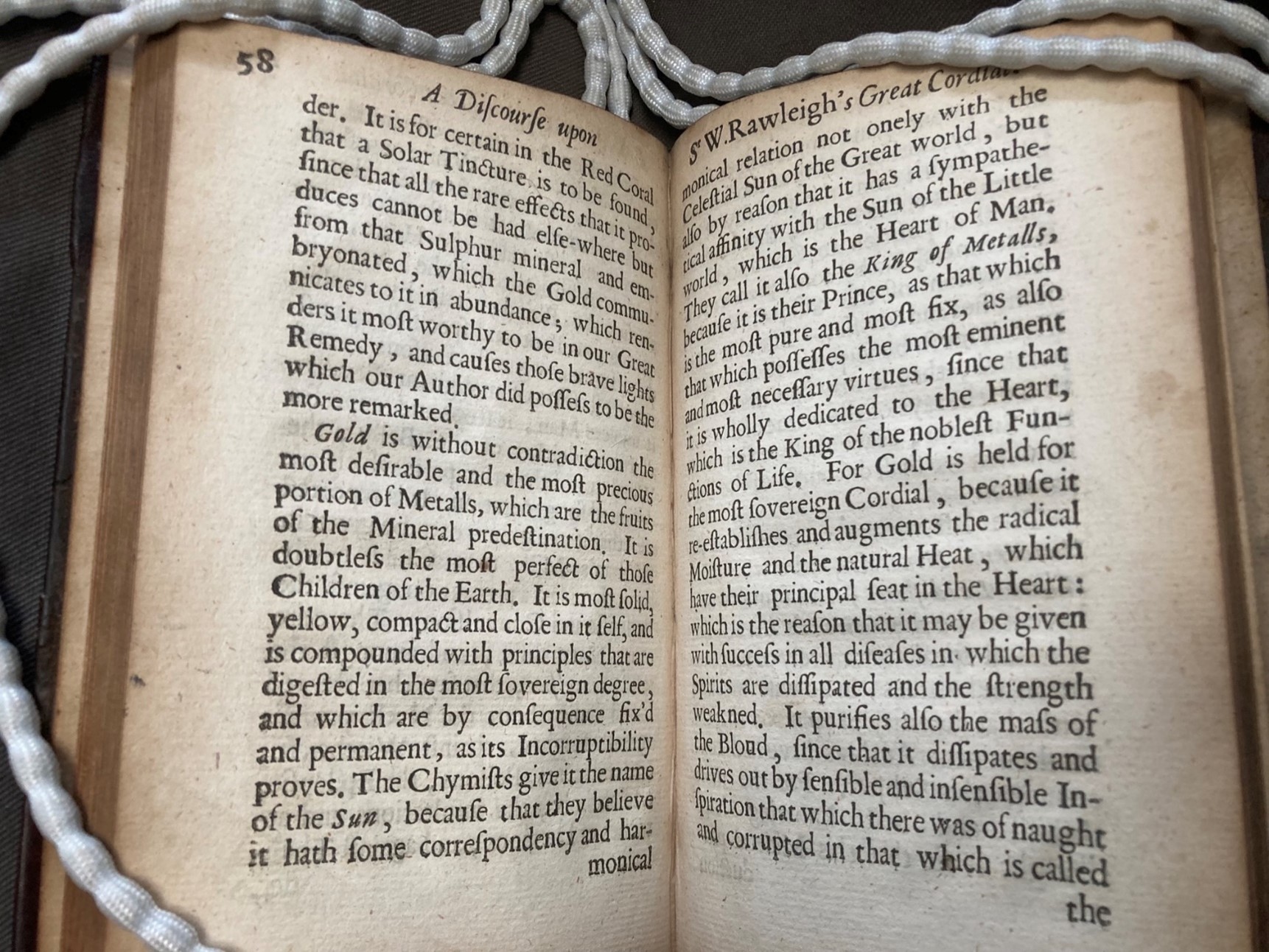

Meticulous detail is also placed upon a certain astounding ingredient, which is the addition of gold to the cordial. Broken down in detail of preparation, gold had been used for centuries as a medicinal ingredient, but it was with the exploration of alchemy and transmutation of the mineral into its liquid form where it reached its legendary standard as the ‘elixir of life’ or ‘aurum vitae’. The inclusion of gold and its process/preparation highlights the science and chemistry of alchemical pursuits of the period; this wasn’t considered the work of a quack mixing together random ingredients, but a scientific pursuit with unfathomable discoveries and mysteries. It feels fitting that the preparation and involvement of the ‘king of minerals’ plays such an integral role in Raleigh’s recipe, for the man that spent so long chasing the mineral to mythical cities.

Additionally, one of the other more luxurious ingredients within the cordial is the use of ambergris, produced from the digestive system of the sperm whale, at the time of publication ambergris was still relatively unknown and great speculation over its true origin was rampant. This discourse does locate the source to the sea, but its form and location are described with a sense of mystery and change, with its healing attributes being linked to everything from strengthening the heart to purging the lungs with healing vapours or salts.

Ambergris, and many of the other ingredients in the cordial, almost seem to be here for the sake of opulence and wealth of medicine; the great cordial was designed for royalty and the elite of society, and the ingredients reflect this with the sheer value and scarcity of many of the materials. With this in mind, it can be easy to understand how Raleigh’s cordial could be conceived as the ultimate cure all, a mythical elixir of such extraordinary qualities that it cured royalty and was quite literally made from gold. Also, to finish it off, if the excess of over forty ingredients left a bitter taste in your mouth, fret not, the recipe also includes a staggering two pounds worth of sugar … a good thing dentistry was not a priority in the 17th century.

The publication of this discourse and recipe allows Raleigh’s legacy to live on, and despite his rather abrupt execution in 1618 following his final failed expedition to find his mythical El Dorado, and several violent encounters with the Spanish. The fact that his work within alchemy was still influential decades later, showed that beyond the guise of the courtier and explorer, he was a renowned man of early modern medicine. It is why it seems fitting that the great cordial, much like the many other exploits of Raleigh, would take on a mythic quality due to its collection of such outlandish properties; it seems appropriate for the man so embroiled with myth and legends, of golden cities and lost colonies … and a bezoar or two.

Alice Bertonlini, heritage library placement student

References

N. Le Fevre, A discourse upon Sr Walter Rawleigh's great cordial, 1664

Historic Royal Palaces, Sir Walter Raleigh at the Tower of London

Hagith, Nagar, Encyclopedia of Gastroenterology, Elsevier, 2004, pages 174-175

Rubbiani, R., Wahrig, B. & Ott, I. Historical and biochemical aspects of a seventeenth century gold-based aurum vitae recipe. J Biol Inorg Chem 19, 961–965 (2014)

Wilding, Mark, A brief, fascinating history of ambergris, The Smithsonian, 2021

There are various volunteering opportunities available with the RCP Archives, Heritage Library and Museum: see our volunteering webpage for more details.