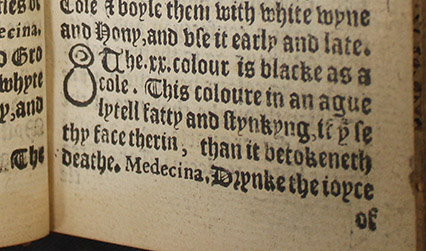

The 20th colour is black as a coal. This colour in an ague [fever], little fatty and stinking, if you see your face therein then it betokens death. Medicina: Drink the juice of celandine and mullein or treacle with white wine early in the morning and late in the evening.

This is one – probably the most alarming – sections of advice on interpreting the colour of urine from the book The seynge [seeing] of urynes, published around the year 1548.

Diagnosis by the examination of urine was a common part of medical theory and practice in the medieval period and later. Manuscript and printed medical textbooks for learned physicians, written in Latin, included diagrams and details explaining how to interpret the evidence of a patient’s urine. From the early 16th century onwards printed books for non-specialists written in English, like The seynge of urynes, became an important part of medical publishing.

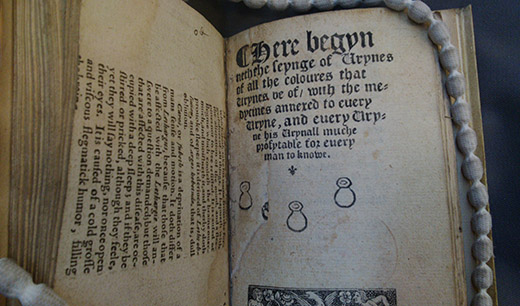

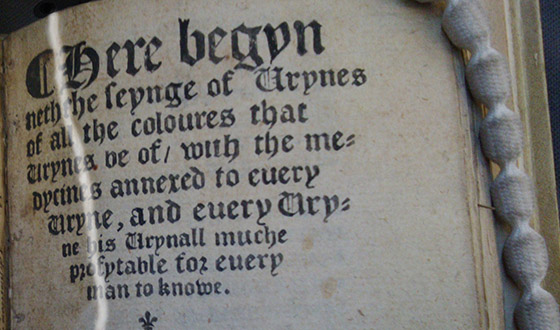

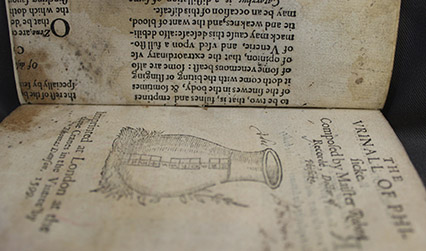

The seynge of urynes describes 20 colours of urine, from ‘white as clay water’, through ‘as red as a burning coal’ to black ‘like a raven’s feather’ or ‘like a coal’. Each entry explains what the colour indicates about health and disease, followed by a recommended course of treatment. Each colour is accompanied by a small illustration of a urine flask, the vessel used by physicians to examine a patient’s urine.

Lots of books were published on this subject, offering general medical advice to a non-specialist audience. The first edition of The seynge of urynes was published in London in 1525, and it reappeared at least 10 times throughout the 1500s. There are two copies in the RCP library, both probably dating to 1548 of thereabouts. Both show evidence of use and handling over the last 470 years, but one is particularly rich in evidence of the hidden lives of books.

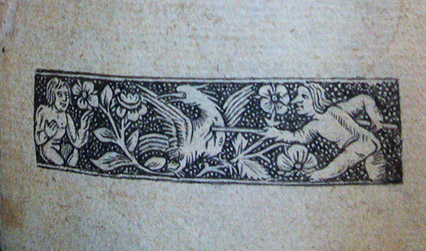

Look closely at the title page. There’s a rip running from the top left, down half the page’s height and then off to the left edge. To the left of the tear you can see the original printed page. Everything to the right of and below the tear is a reproduction made by hand with a pen and ink. This kind of imitation or replication of printed text is known as a ‘pen facsimile’. They can be very hard to spot: in this instance, the woodcut illustration at the foot of the page is particularly finely executed.

Opposite the title page of The seynge of urynes is some printed text running sideways. This is a discarded sheet from another printed medical book, Petrus Pomarius, Enchiridion medicum containing an epitome of the whole course of physicke (London, 1609). It was used as a wrapper or cover for another work, Robert Recorde’s Urinall of phisicke (1599). At some point the Urinall of phisicke and The seynge of urynes were brought together into a single volume, but the old wrapper was kept in place.

The pen facsimile and changes in the binding show how these two little books have been used and reused over the centuries.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian