The print collection of the Royal College of Physicians, part of the RCP museum, is full of portraits depicting the great medical minds of history. It is a showcase of the men and women who have contributed to the study of medicine, and science overall; representing ground-breaking advancements over centuries of research and scientific investigation into the human body.

But not entirely.

As a Museum Studies student and volunteer with the Royal College, I have been conducting a thorough audit of the Prints Collection. This involves sifting through boxes and boxes of portrait prints to verify the location with our online databases, and flag any misplaced prints in the collection. In every box, there are influential physicians, doctors for the royal family, and figures in the history of science. Among them, however, are imposters.

Quack physician

In one box, a past curator wrote ‘QUACK PHYSICIAN’ on the back of a print, almost in disgust of the individual’s actions. The unknown curator was referring to Adam Donald, an 18th century quack physician known as the ‘Prophet of Bethelnie’.

Born in 1703 north of Aberdeen, Donald thrived in an era where witches were more than just campfire stories. While disabilities prevented him from a life of manual labour, his mannerisms, charm, and apparent skills led to his calling as a spiritualist. Donald was called to consult on all matters related to health by the local citizens. A habit of lurking through churchyards ‘speaking’ with the dead fuelled his supernatural legitimacy, while owning several books in other languages (of which he could not speak) contributed to his scholarly image among the townspeople. Prescribing remedies ranging from milk baths to singing on chimneys, he could do no harm. If a death occurred it was the patient’s mistake for not following the ‘Prophet’s’ orders, never Donald’s. While Donald’s wife kept his secret during their marriage, his daughter exposed him as a quack and fraud following his death in 1780.

While Donald was referred to as a ‘quack’ in an 1844 edition of Tegg’s Magazine, the term has much older origins. Simply put, a ‘quack’ is ‘a fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill.’ The mark of a true quack is prescribing treatments with the full knowledge that they do not work. The origin of the word is from the old Dutch quacksalver, meaning ‘one who quacks (boasts) about the virtue of his salves.’ The 18th century, with limited regulations on the sale of medicine in England and France, saw a rise in quack doctors. These charismatic individuals were able to persuade all classes of society towards their hoax cures, with limited repercussions.

A most impudent quack doctress

Ann Manning, represented in our collection, is another known quack who took advantage of the 18th century English working class.

Described as ignorant and a drunk, she nevertheless possessed the skills needed to back-up her exuberant claims. A page clipping stored with her portrait describes her as a ‘most impudent quack doctress,’ and also advocates for greater regulations in the medical field. She is held up as an example of the abuse present without proper oversight. Specifically, the author calls for the establishment of ‘dispensaries in every populous town’ in the nation to save the lower classes ‘from the fangs of such pests [quacks] of society.’ Manning illustrated to the author the typical English quack doctor who benefitted from these limited regulations. The creation of sanctioned dispensaries run by licensed physicians was seen as the cure to quacks.

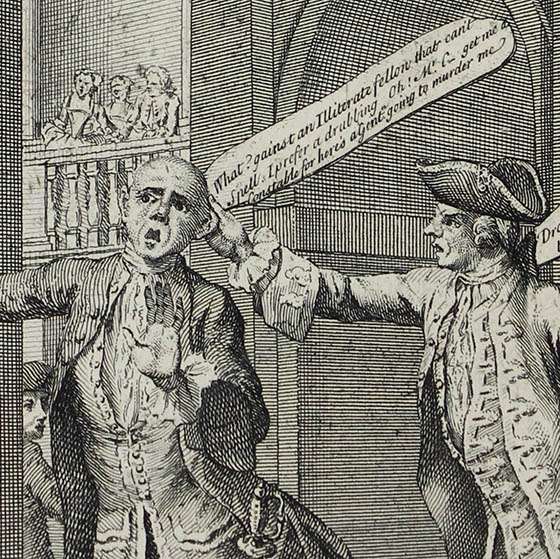

The print of Ann Manning in the College’s collection, depicting her with a patient outside her cottage, further presents her as a Dickens-style villain preying on the needy. Quack remedies, such as flesh regeneration, are advertised on her cottage in the print. At her feet, a leaflet declares ‘Lies told faster than a Horse can gallop.’ In this early 19th century print, Manning is clearly the antagonist and seen as a pariah on society.

The knighted quack

Lastly, the well-known and respected scientist John Hill, who has been accused of quackery, can be found in the collection. As with Adam Donald’s print, a past curator felt it necessary to single him out as a quack amongst the collection.

![Handwritten note reading 'Sir John Hill [quack]'.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/blog%20Curator%27s%20note%2C%20written%20on%20the%20back%20of%20PR1905_0.jpg)

Active around the same time as Donald, Hill was granted a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh. Through his career, he was eager to become one of the most learned men of his time. To this end, he called himself ‘Sir’ John Hill, after receiving the Order of Vasa from the King of Sweden in 1774. For his work with botanicals, The Times called Hill ‘the Linnaeus of Britain’ following his death. In addition to these scientific achievements, Hill was a prolific writer. After being rejected for membership into the Royal Society, he wrote ridiculing satires about its members. Depicted in the College’s print, Hill was attacked at Ranelagh Gardens on 6 May, 1752 by Capt. Mountfort Brown over the growing attacks between authors.

To supplement the costs of his writings, Hill began growing herbal remedies at his home in London. His ‘Pectoral Balsam of Honey’ was billed as a cure for all breathing and throat conditions, and returned a fair amount of money to its creator. In fact Hill’s widow continued producing the ointment for years after his death. It is still being debated whether this cure-all remedy qualifies Hill as a quack or a genius. No matter the true answer, he will forever be labelled as the former according to the scribblings of one Royal College curator.

All three individuals show some, or all, of the characteristic of a quack: prescribing cures known to not work, preying off the fears of the people, and a charm that captures their patients. Upon the death of Donald and Manning, they were known to be frauds and generally shunned by society, while Hill is a debate still occupying some circles. Despite our general awareness towards the practice of ‘quackery’ today and the increased regulations and licencing on the medial field, there are still quack doctors prescribing false cures around the world. These prints, and the countless others in the collection of the Royal College, should serve to remind us of how far medical practice has come over the past centuries, and yet how somethings may never change.

Zachary Veith, museum intern

Explore the Royal College’s collection of prints and artefacts via the online catalogue.