“A noble heart must answer to the sacred call of ‘friend’”

The records of Sir James Mackenzie, and Lena Guilbert Ford

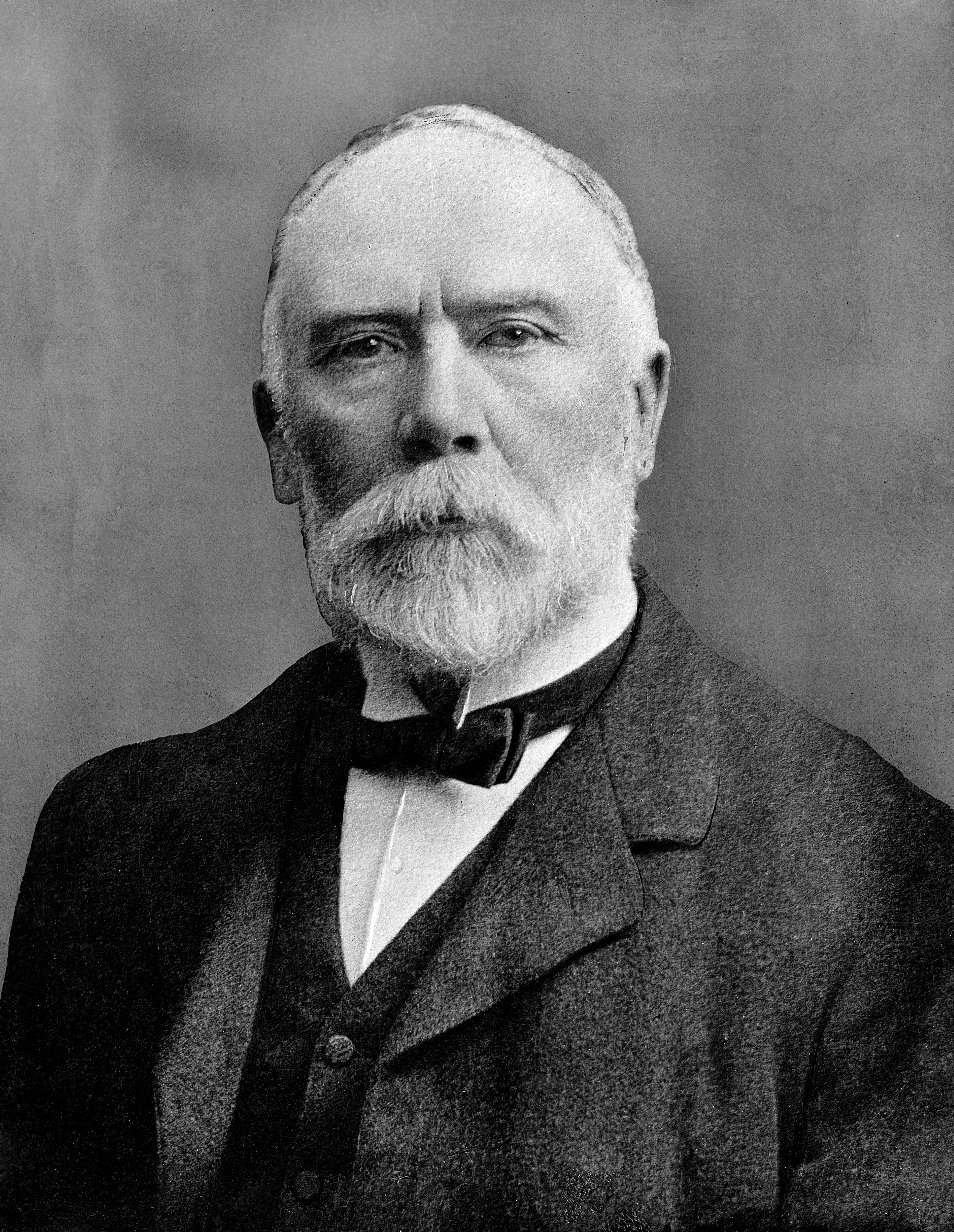

Sir James Mackenzie (1853-1925) was one of Britain’s most well-respected cardiologists during the early part of the 20th century. During his years as a consultant in London his expertise was sought by patients from all over the country, and occasionally as far afield as the USA and Canada. During my time working with the Mackenzie collection, the files have revealed to me a vivid picture of a man deeply dedicated to his work. Mackenzie believed that the best tool for the advancement of medical science was case work on patients, and in his later years he founded the St Andrews Institute for Clinical Research (renamed the James Mackenzie Institute for Clinical Research at St Andrews after his death).

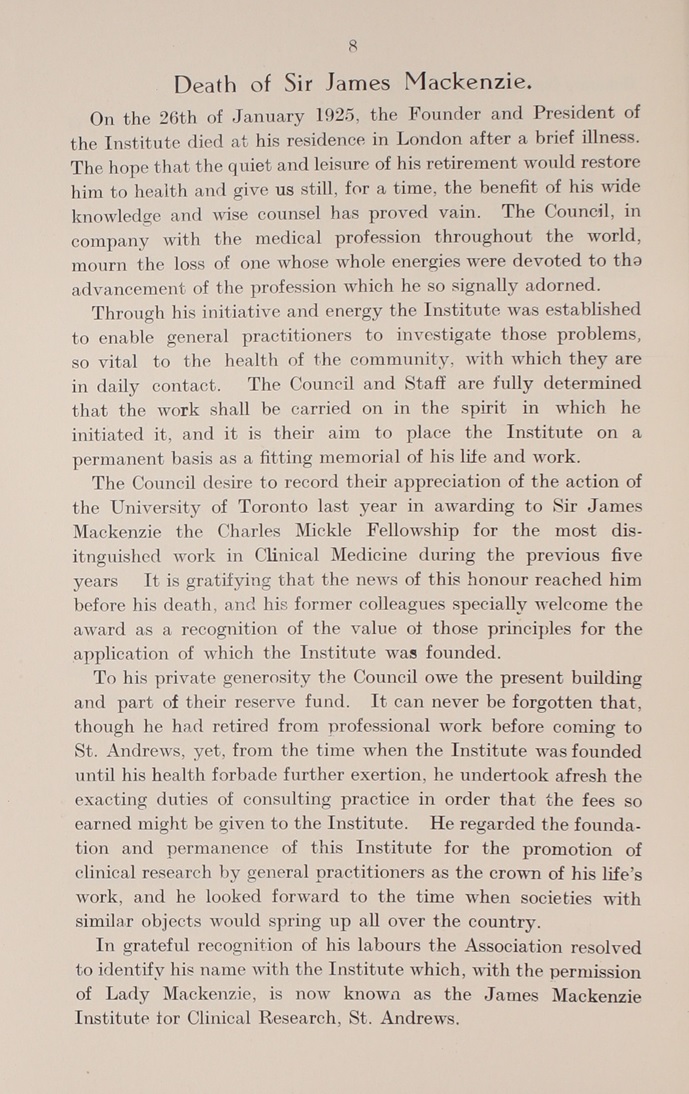

The Mackenzie collection at the RCP contains the annual reports of the Institute, including a statement on Sir James’ death in 1925. The Council describes him as ‘one whose whole energies were devoted to the advancement of the profession which he so signally adored’ (Sixth annual report, MS6058)

Mackenzie had suffered from heart problems of his own throughout his life, dying at the age of 72 of angina pectoris, a condition to which he devoted extensive research (MS6061). Before his death he requested that one of his colleagues perform a post-mortem on his heart, and the results of this examination were published in the British Heart Journal in 1939.

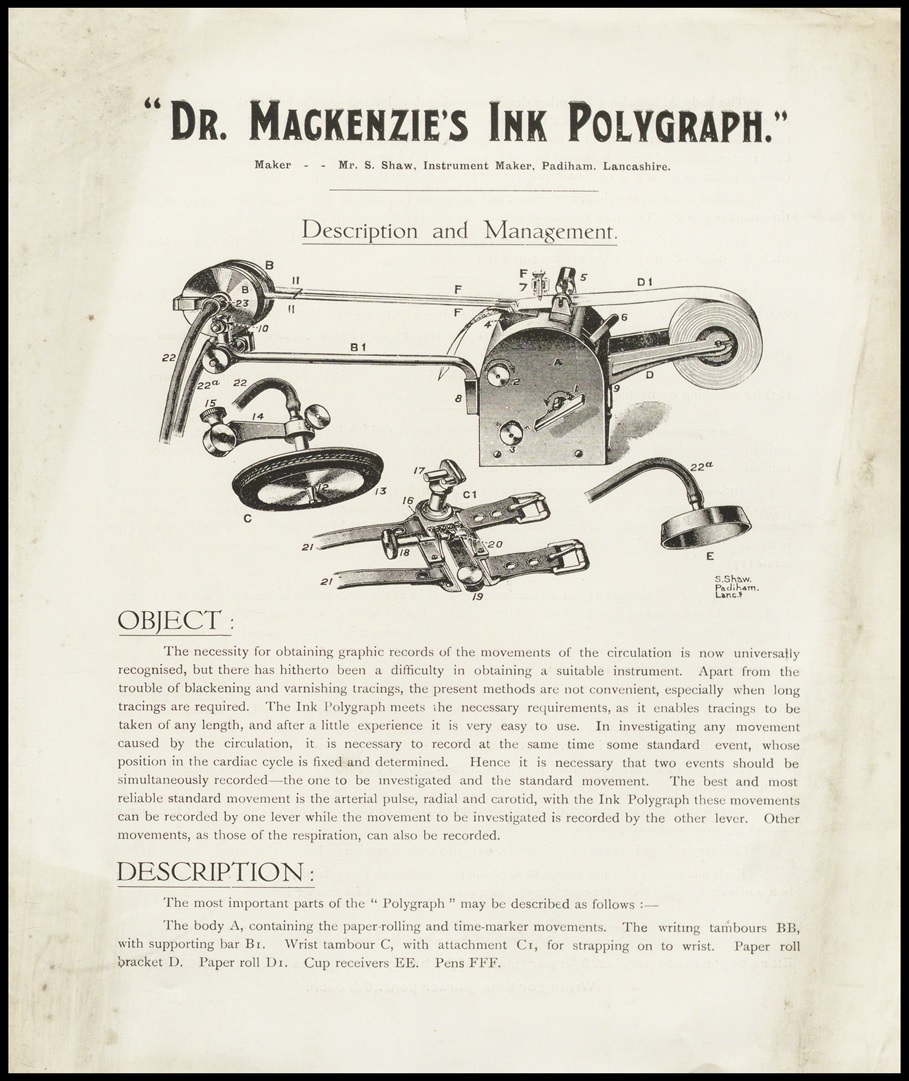

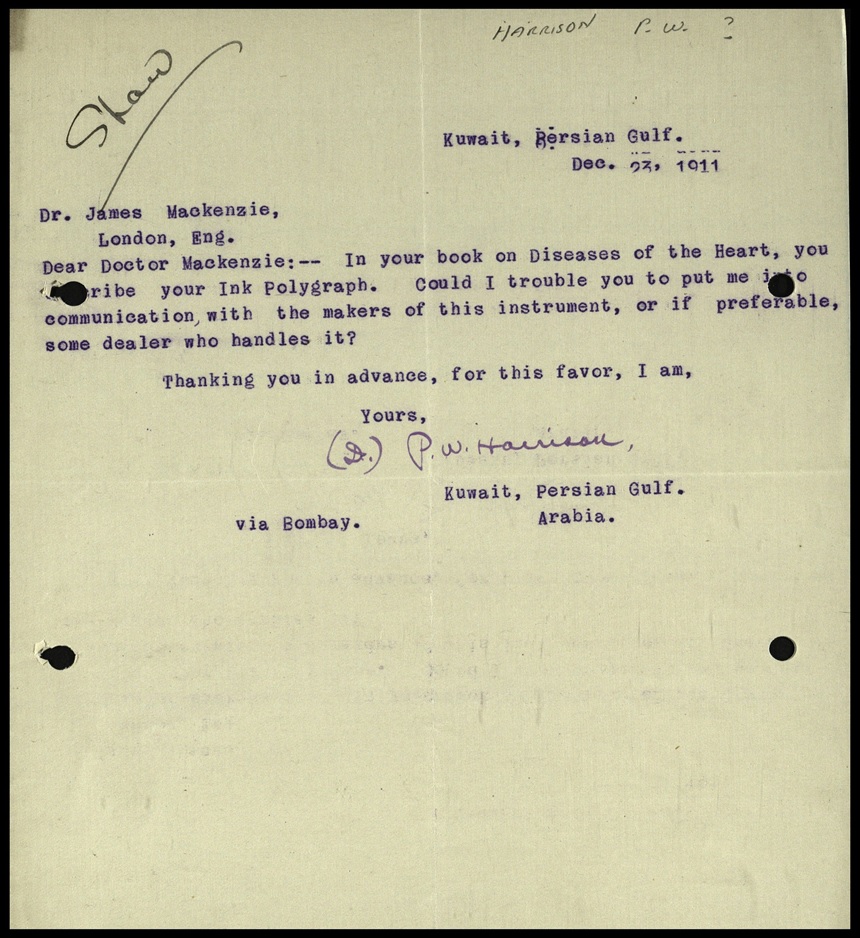

One of the most exciting elements of the Mackenzie collection is the hundreds of polygraph charts and tracings within his case notes. In his 1902 book The Study of the Pulse, Mackenzie described a machine he called the ‘polygraph’ that he used to measure the arterial and venous pulses in conjunction with the heartbeat in order to detect irregularities and distinguish between those that were harmful and benign. The word polygraph is now associated with lie detection, due to the invention of the lie detector polygraph in 1921, but at the time the instrument seems to have gained an international reputation, as evidenced by a 1911 letter from Dr P.W. Harrison in Kuwait requesting access to information about the machines and their manufacturers (MS6054).

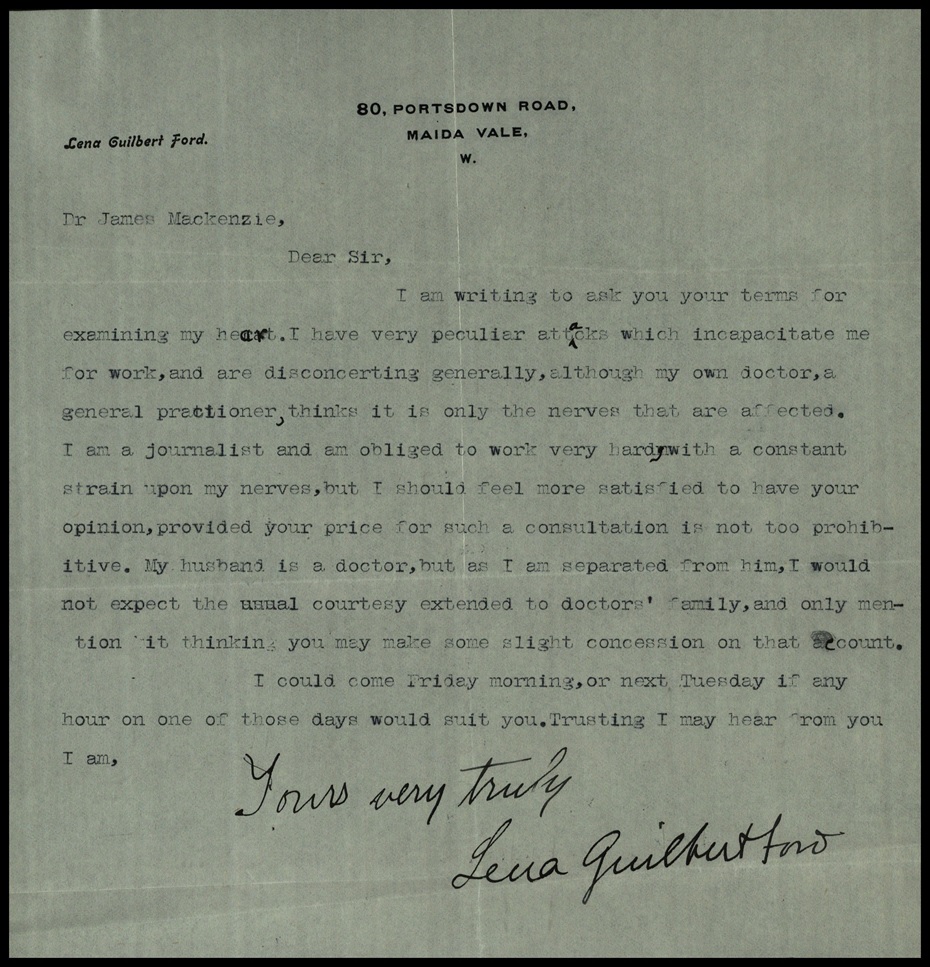

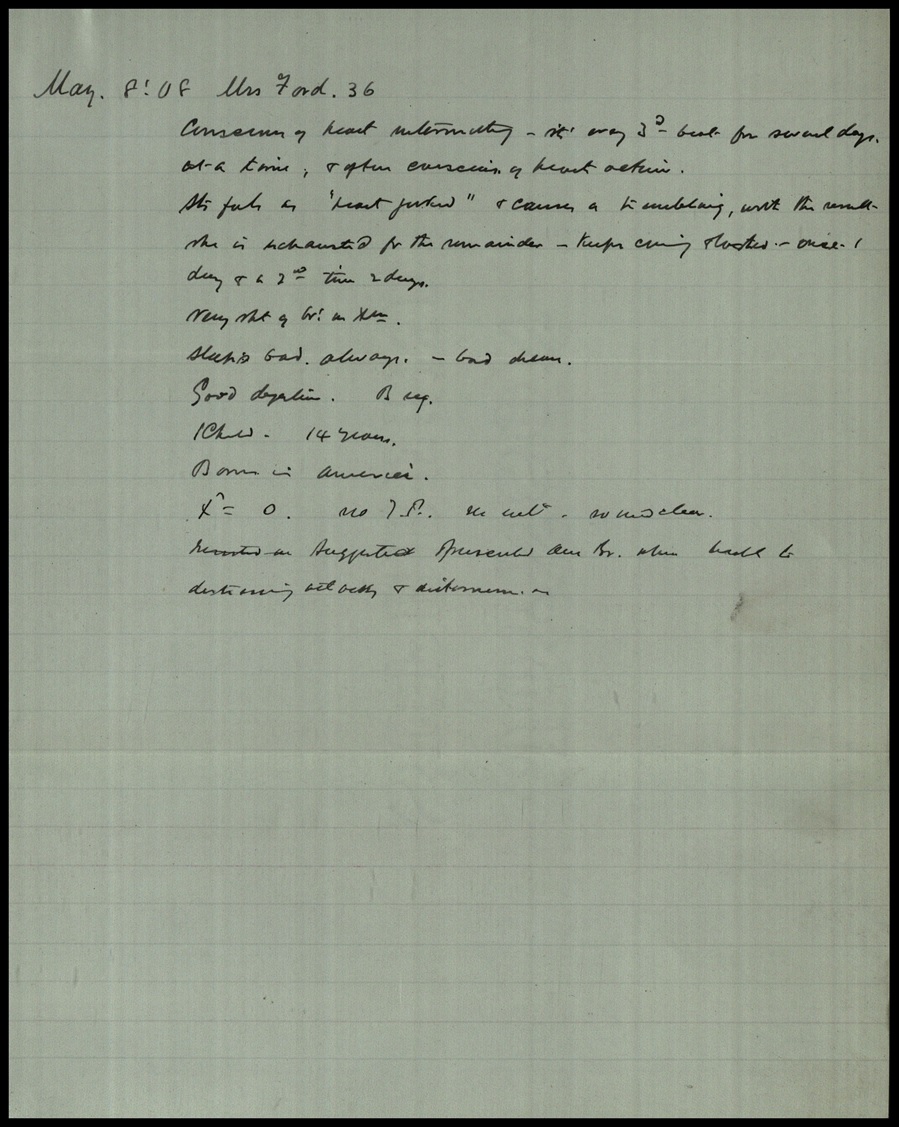

Many well-known and high-status people were seen by Mackenzie during his time as a consultant, but I was particularly interested in the notes on Lena Guilbert Ford (1870-1918). She wrote to Dr Mackenzie in 1908 requesting a consultation regarding the ‘very peculiar attacks which incapacitate me for work’, and states that in her role as a journalist she is ‘obliged to work very hard with a constant strain upon my nerves.’ In her letter (MS6041/1) she also mentions that she is separated from her husband, which was highly unusual for a woman of the time. I was curious to know more about her.

Lena Guilbert Ford was born Lena Guilbert Brown in 1870 in the USA but relocated to London with her mother and son after separating from her husband, the physician Harry Hale Ford. Although she does not mention any work as a lyricist in her letter to Dr Mackenzie, Lena is best known for writing the lyrics in 1914 to the popular First World War song ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’, composed by Ivor Novello (1893-1951).

According to Mackenzie’s notes on her case (MS6041/1), Lena was in 1908 suffering from an extrasystole, an extra heartbeat caused by a premature contraction of the heart, and also from what he describes as ‘nerve exhaustion’. Her condition was evidently not too serious as he only saw her once, but her life was nevertheless cut short when Lena and her son were both killed after their home was hit by a bomb in 1918, becoming the first American casualties of a German air raid on London. Lena was 48.

Although her name is not well known now, it seems she did gain some recognition during her lifetime. A year after her death, a letter to the editor of the American military newspaper Stars and Stripes from the president of Elmira College, from which she graduated in 1887, states that they are ‘raising a fund to erect a memorial building in her honor’. Although this building seems to never have come to fruition, there is to this day a memorial fireplace in her honour in Elmira College’s Hamilton Hall, a fitting tribute to her most well-known work.

Matilda Wood

Archives volunteer placement student