The Great Fire of 1666 was one of the greatest tragedies to befall the City of London. The material damage sustained is well documented – some 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, six chapels, the Royal Exchange, Custom House, 52 company halls and three city gates to name but a few – but remarkably, the human side to the story is equally well recorded, and those who lived through it are able to make their voices heard today, over 350 years later.

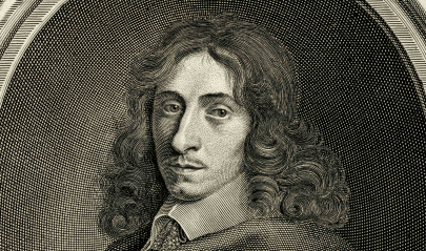

Two of the great diarists of the 17th century, Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) and John Evelyn (1620–1706), lived – and wrote – through the five days of the fire, from Sunday 2 to Thursday 6 September 1666. Pepys described in detail how most people he encountered during those days were more concerned with saving their possessions than with fighting the fire:

Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff … and nobody, to my sight, endeavouring to quench it, but to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire.

Pepys’s quote is particularly poignant because the Great Fire started as so many other fires in the City frequently did: small, slow-spreading and ultimately containable. That residents were more concerned with saving possessions than fighting the fire is one reason why the fire spread to become the ‘most horrid malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire’, that Pepys describes.

Pepys’s diary entries are peppered with anecdotes of daily life that give us an idea of what living through the fire was like, albeit for the more fortunate sectors of society. Pepys and his guests ‘fed upon the remains of yesterday’s dinner, having no fire nor dishes, nor any opportunity of dressing any thing.’ Somewhat amusingly, two days after the fire started, ‘Sir W. Pen and I did dig another [pit in Pepys’s garden], and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.’

The diary of Pepys’s contemporary John Evelyn concurs with Pepys’s observations:

The Conflagration was so universal, & the people so astonish’d, that from the beginning (I know not by what desponding or fate), they hardly stirr’d to quench it, so as there was nothing heard or seene but crying out & lamentation, & running about like distracted creatures.

Like Pepys, the language Evelyn used still evokes the horror felt by those who witnessed the ‘miserable & calamitous speectacle’:

God grant mine eyes may never behold the like, who now saw above ten thousand houses all in one flame, the noise & crakling & thunder of the impetuous flames, the shreeking of Women & children, the hurry of people, the fall of towers, houses & churches was like an hideous storme, & the aire all about so hot & inflam’d.

In contrast, the memoirs of William Taswell, a 14-yearold pupil from Westminster School, provide a more light-hearted – if macabre – view of the unfolding tragedy.

On Thursday 6 September, Taswell went to explore the ruins of St Paul’s Cathedral. The destruction of the seemingly-invincible stone monument two days before was witnessed by Evelyn: ‘the stones of Paules flew like granados, the Lead mealting down the streetes in a streame, & the very pavements of them glowing with a fiery rednesse’. Taswell was not disturbed by the bodies that had been revealed by broken tombs, nor by the corpse of a badly burned victim of the fire that he encountered in the ruins; instead, he clambered over the rubble of the masonry, as if it were an adventure playground, and filled his pockets with lumps of melted bell metal as souvenirs.

These eyewitness accounts are part of the story told in our previous exhibition, ‘To fetch out the fire’: reviving London, 1666.

Sarah Backhouse, exhibitions officer

Sources:

Taswell W. ‘Autobiography and anecdotes by William Taswell D D’, ed. G P Elliott, Camden miscellany II (1853), pp. I-37

Tinniswood A. By permission of heaven: The story of the Great Fire of London. London: Pimlico, 2004