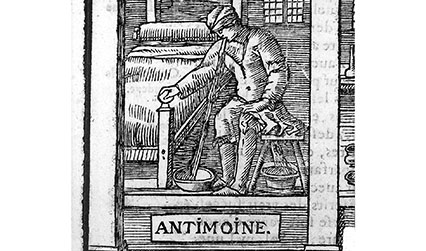

A 17th century antimony cup is our latest curator’s curiosity, one of 12 objects from the RCP library, archive and museum chosen as part of the RCP500 celebrations.

When we think about medicine in the past, bloody and brutal operations and treatments often come to mind. If you were unlucky enough to fall ill in the 17th century, you most likely would have been bled and purged or sent to the barber-surgeon for an amputation. Bleeding and purging (by vomiting or by clearing the bowels) are ancient medicinal cures characteristic of Galenic medicine. Since at least the 2nd century, physicians inspired by Galen had been prescribing plant compounds which supposedly re-balanced the humours by purging. But this ancient tradition was challenged in the 16th century with the introduction of a new breed of chemical medicines: mercury and antimony.

In the 16th century, the Swiss physician Paracelsus (1493–1541) introduced a new medical philosophy which challenged traditional notions of the humours in Galenic medicine. Blending together folk medical traditions and alchemy, this renegade doctor introduced the idea of the ‘mineral cure’ – using metallic chemical compounds to treat disease. It is from this school of thought that the widespread use of the heavy metals antimony and mercury in European medicine was born.

In general, physicians of the era were suspicious of these new cures, but they were taken up enthusiastically by many apothecaries. One classic example of this new mineral medicine was the antimonial cup. Such cups would be prescribed by apothecaries (and the occasional doctor) or sold directly to patients. The typical instructions for its use were:

Fill it with White wine and put a clove or two in it, and a little mace, then let it stand all Night and ye Next morning drink the Wine and it will taste of nothing but wine, and will work safely first by a Vomit, and then by Stools also… And accordingly as you would have it work, either gently or strong, You may put ye wine in Sooner or Later at Night.

Having absorbed the poisonous elements of the cup, ingesting the wine would result in intense purging in the patient – from which they either recovered, or did not. We believe our cup may have killed at least two of its patients.

Such violent medicine was not without its critics. The 17th century French physician Guy Patin once exclaimed ‘May God protect us from such drugs and physicians!’ The adoption of mineral medicine caused great concern from the medical profession, particularly in France where the use of antimony was banned for 100 years. In Britain, many physicians were similarly concerned by the use of antimonial preparations and cups, particularly by apothecaries. Despite a formal ban on the sale of antimony from 1566, antimonial cups continued to be sold and used until the late eighteenth century, including famously by Captain James Cook (1728–1779).

Yet this was not the end of antimonial medicines. Antimony found its way into almost every medicine chest in the country in the Victorian era in the form of ‘tartar emetic’. The nineteenth century brought many new innovations in botanical and chemical medicine, and tartar emetic mixed in wine continued to be used to produce vomiting. Antimony compounds were still being used in the 1970s to treat the parasitic diseases schistosomiasis, its toxic effects working wonders on the worms.

Today, we need to be sure to handle our antimony cups with care, protecting ourselves from coming into direct contact with the metal by using nitrile gloves. There are only six known examples of such cups in Great Britain, two of which are held here at the Royal College of Physicians One of our antimony cups – purchased by Baldwin Hamey Junior in 1637 – is this month’s curator’s curiosity.

Kristin Hussey, curator

In celebration of our anniversary year, the RCP Museum team has developed a new heritage trail called Curator’s Curiosities to share with the public some of the more curious stories behind our special collections. Alongside special purple signs around our Regent’s Park building, we are featuring monthly rotating displays of treasures from our stores which are rarely exhibited.