The RCP’s current exhibition, ‘This vexed question’: 500 years of women in medicine, displays thought-provoking objects from institutions around the country. One incredibly poignant object is an embroidered handkerchief owned by the Priest House, part of Sussex Archaeological Society.

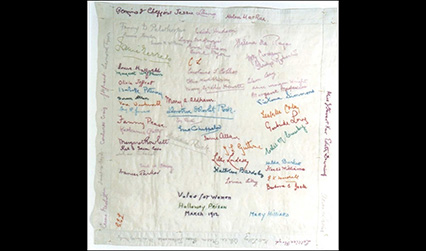

The Suffragette Handkerchief was signed, in embroidery, by 68 women inmates at Holloway prison in 1912. These inmates were suffragette prisoners, serving varying sentences for their participation in the March 1912 window-smashing demonstrations in London, organised by the Women’s Social & Political Union. Between 1905 and the First World War, over 1,000 women and about 40 men were imprisoned because of their involvement in suffrage activities like these.

Many of the names on the handkerchief have been identified by researchers Barbara Miller and Antony Smith – you can read more in their blog here. Of particular interest to the exhibition is Alice J. Stewart Ker (1853–1943), a Scottish doctor who worked as a surgeon at the Children’s Hospital in Birmingham, and as honorary Medical Officer to the Wirral Hospital for Sick Children. Dr Ker was active in the Birkenhead Women’s Suffrage Society, and in 1912 was sentenced to three months for smashing a window at Harrods department store.

These women were not just prisoners, however – they were also survivors of the famous Holloway hunger strikes. This strategy was used by suffragette inmates as a means of non-violent protest, and of passive resistance to the injustices suffered because of their gender. The hunger strikers were protesting in particular about their treatment in prison – they were classified as common criminals rather than political prisoners, and were held in harsher conditions as a result.

At Holloway Prison, suffragette inmates who went on hunger strike were sometimes brutally force fed. Prison doctors or attendants would use stomach pumps, nose tubes and gags to force food into the stomach. The practice was painful and dangerous, but was rationalised by some authorities – including the president of the RCP Sir Thomas Barlow – as being life-saving, and was considered a way of protecting the state from charges of manslaughter. Suffragette doctors including Louisa Garret Anderson disagreed, stating that ‘The reason they do not take their food is political, not pathological, and the appropriate treatment is statesmanship, not a stomach tube.’

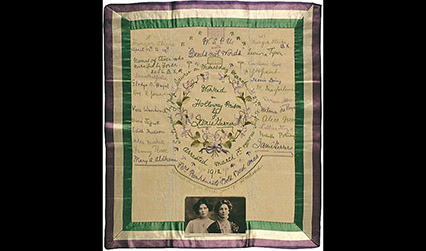

Other handkerchiefs embroidered by suffragette inmates survive today. Also in 1912, Janie Terrero stitched the names of 19 fellow prisoners at Holloway, all of whom had taken part in the hunger strike of 13-19 April, and ‘who were fed by force’. Terrero was one of 200 women sentenced on 27 March to four months’ imprisonment – as punishment for taking part in a window smashing campaign, just as Alice Ker was in that same year. During the campaign, nearly every shop window in Piccadilly Circus was destroyed, using stones or ‘toffee hammers’, concealed up sleeves.

The use of embroidery by these women to record their experiences is significant. The delicate handiwork required to sew a signature presents a stark contrast to the grim reality of prison life. In the emerging accounts of imprisonment in Holloway, we learn that after four weeks, women were allowed to leave their dismal cells to ‘take their needlework or knitting to the hall downstairs, which was more airy, and sit side by side, although talking was still forbidden.’ Through the handkerchiefs, the women subverted the materials available to them in prison, and by using this typically intimate, ‘feminine’ craft, they could make a powerful point about the restrictions placed on women’s right of self-expression, endured in both incarceration and in freedom. These textiles gave voices to the women named.

Sarah Backhouse, exhibitions officer

The RCP exhibition This vexed question: 500 years of women in medicine opened on 19 September 2018 and runs until 18 January 2019.