The Royal College of Physicians was founded in 1518 to regulate medical practice, and one of the key powers contained in its royal charter was the ability to grant licenses to practice medicine in London and its environs:

We [i.e. King Henry VIII] have also granted to the same President and College or Commonalty, and their successors, that no one in the said City [i.e. London], or for seven miles in circuit of the same, shall exercise the said faculty [i.e. medicine], unless he be admitted thereto by the said President and Commonalty, or their successors

Translation of Latin text from MS4917, Charter of incorporation of the College, 23 September 1518.

But how did the college actually decide who was qualified and sufficiently expert in the subject? What was on the medical syllabus before the 20th century?

The earliest surviving rules and syllabus for the RCP examinations come from the statutes of the college codified in and around 1555 by RCP president John Caius (pronounced ‘Keys’).

There were five sections in the exam:

- medical theory

- causes of disease, symptoms and diagnosis

- methods of treatment

- materia medica (substances used in medicines)

- the ‘use and practice of medicine’, which included the conditions under which patients should be purged or bled, the use of soporifics or narcotics, the positions of the internal organs, and the use and measuring of clysters (enemas).

The exams were led by the four censors of the college – fellows elected into the role and responsible for licensing and discipline – along with the college president. If the examiners already knew a candidate and believed him (the exams were only open to men) to be skilled and knowledgeable then he only needed to take the fifth section of the exam. Anyone else had to complete all five sections. The exam took place over several occasions at intervals of three months.

Set texts

Each of the first four sections of the exam had set texts assigned to them. At each exam the censors would pick three passages from the texts and ask the candidate questions based on them. The candidate was then given copies of the relevant books (without an index in them) and had to find the correct places in the books and explain how they related to the questions.

The set texts all came from the works of the Roman medical author Galen (c.129–c.216) and are laid out in detail section-by-section in the statutes of the college: see the appendix to this post for the full list of 17 titles. It might seem like a pretty substantial list, but it’s only 17 out of the more than 120 works that have been attributed to Galen, whose works were the foundation of the medical curriculum for centuries.

Sadly, there are no copies of Galen’s works in the RCP Heritage Library today that we can identify as the exam copies: perhaps they were used to destruction by generations of nervous candidates and eventually fell apart. There are, however, multiple copies of Galen’s works, many of them annotated by readers in the 16th and 17th centuries, showing how heavily studied his writings were.

1601: streamlining the exams

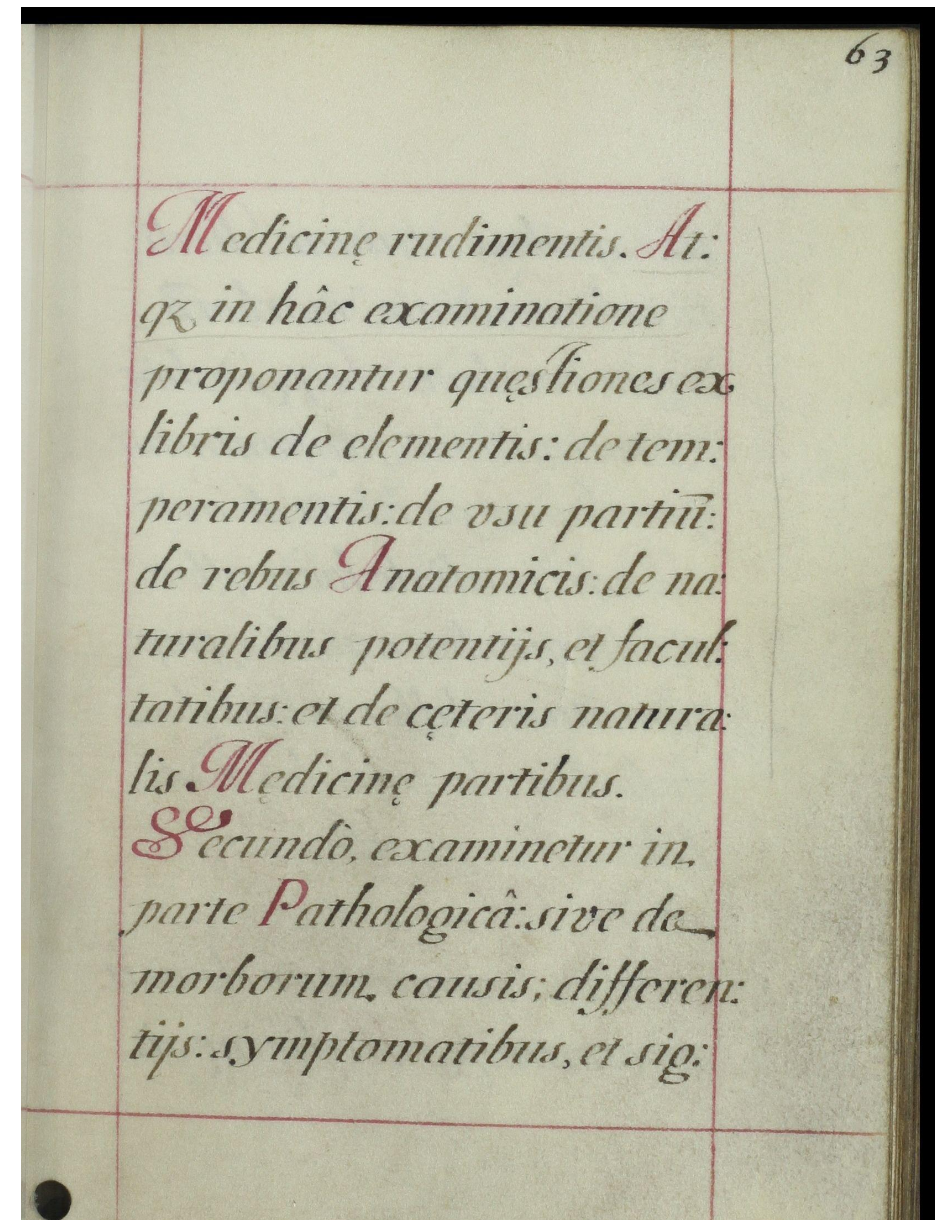

The statutes of 1601 (MS2012/81-85) marked a change in the examination. The previous five-section format was reformed into a possibly more manageable three:

- physiology, defined as ‘the science and knowledge of physic’

- pathology, ‘the causes of and differences between diseases, and the symptoms and signs which physicians use to understand the essence of disease’

- the use and practice of medicine, meaning ‘the manner, means and method of healing’

The list of set texts however remained the same, with the Galenic works from the previous sections 1, 2 and 3 being carried over, and those from the old section 4 also being incorporated into the new section 3.

This three-section format (physiology, pathology and practice) continued for hundreds of years, and Galen’s texts were the set works until at least the mid 1730s, as documented in the statutes of 1735–6 (MS2012/69). By this time, the set texts must have seemed increasingly anachronistic, given the ongoing developments in medical theory and understanding which challenged traditional Galenic approaches to health and disease.

The 1765 statutes (MS2012/75) lack any mention of the Galenic texts (or any other set texts), with very little detail about how candidates would be examined, except to say it would take place over three meetings on the by-now standard three topics of physiology, pathology and therapeutics. But that wasn’t the end of ancient authors as modern medical authorities: they creep back onto the syllabus in the statutes of 1834 (see Clark’s History vol. 2), which explain that that candidates will have to explain extracts from the works of not only our familiar friend Galen, but also the ancient Greek Hippocrates, and of the second-century AD Greek physician Aretaeus.

Mind your language

The examinations were almost always conducted in Latin. In late 1721, a candidate named Butler requested to be examined in English, and the president therefore raised the question with the college fellows at one of their regular meetings. On 22 December 1721, the fellows decided that ‘none should be examined, but in Latin, without the approbation of the College’. That is to say that you could take the exam in English, but only if you got prior explicit approval from the college authorities. The Mr Butler in question was questioned in English but was still required to interpret the Latin text of one of Galen’s works, and the college concluded that his knowledge was unsatisfactory and forbade him to practice.

In practice, this allowance seems only to have been granted to a small number of candidates to become extra-licentiates those licensed to practice outside London and its immediate environs, and it didn’t stay in place for particularly long. By 1765, a new edition of the statutes was published, complete with a note that ‘we wish that the aforesaid examinations may be made only in Latin’ (MS2012/75). The all-Latin mandate was maintained as late as the statutes of 1834, but shortly after that, things began to change.

Pick up your pens

Up to this point in the story, all the exams were exclusively oral: candidates were questioned in person in front of a panel of college censors. But by 1838, the college was printing written examination papers: three six-hour papers to be taken over three days, with each followed by an oral examination. The papers were written in, and to be answered in, English, albeit with a quantity of translation from Latin and Greek from ancient and more recent authors: Galen and Hippocrates frequently appear, as do medical writers such as William Heberden (1710–1801).

The following oral exam could be conducted in English or in Latin at the censors’ discretion. To help candidates prepare for the exams, the college published sample papers in the London Medical Gazette. By 1869, translation from medical writers in French and German were included alongside the classical languages of Latin and Greek.

Major reformations of medical governance and licensing took place in the 1850s, moving responsibility for to the centralised General Medical Council. The RCP membership exams, however, continued without much change: even in 1924 translations from Greek and Latin were an expected part of the exams, alongside more practical questions about diagnosis and treatment. From June 1924, the translation became optional – the exam paper reader rubric indicated that “the languages are not compulsory, but credit will be given to candidates who show a knowledge of them” – and from 1936 onwards only included French and German, and no Latin or Greek. The translation question last appeared in the afternoon paper on September 30 1963, with a German version of a quotation by William Harvey about his research into the circulation of the blood and an admonishment that candidates should try the translation if at all possible.

The RCP examination paper for September 1963 was the last to feature a translation question. The passage from William Harvey can be translated as:

“When I first put my efforts into observing the reasons for the movement the heart in living organisms through vivisection, through my own observations rather than through the books and writings of others, I found the subject altogether difficult and beset by difficulties. And I couldn’t properly distinguish how the systole and diastole related to each other.”

RCP exams today

Though the RCP has long since stopped granting medical licences (that power is held in the UK by the General Medical Council), it still has an important role in setting the syllabi for medical qualifications. As part of the Federation of the Royal Colleges of Physicians it helps develop and deliver the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians of the UK (MRCP(UK)) exam, contributes to setting specialist training syllabi, and runs the Specialty Certificate Examinations taken by physicians in training wanting to join the GMC Specialist Register.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian

Appendix: set texts specified in the 16th century RCP statutes:

1. Medical theory

De elementis secundum Hippocratem (On the elements according to Hippocrates)

De temperamentis (Of temperaments)

De facultatibus naturalibus (Of the natural faculties)

De anatomicis administrationibus (On anatomical investigations)

De usu partium corporis humani (On the use of the parts of the body)

2. Causes of disease, symptoms and diagnosis

Ars medicinalis (The art of medicine)

De locis affectis (On the parts affected by disease)

De morborum causis and De symptomatum differentiis (On the causes of disease and the differentiation of symptoms)

De differentiis febrium (On distinguishing fevers)

De pulsibus Galen wrote several works on the pulse. This may be De Pulsibus Libellus ad Tyrones (A concise treatise on the pulse for students)

In Prognostica Hippocratis Commentarius (Galen’s commentary on Hippocrates Prognosticon)

3. Methods of treatment

De sanitate tuenda (On the preservation of health)

De methodus medendi (On the method of curing diseases)

In librum Hippocratis De victus ratione in morbis acutis commentarii (Galen’s commentary on Hippocrates’ ‘Diet in acute diseases’)

De simplicium medicamentorum facultatibus (On the Powers and Mixtures of Simple remedies)

4. Materia medica

De crisibus (On crises)

In Hippocratis Aphorismos commentarius (Commentary on Hippocrates' Aphorisms)