One of the most unusual items in our museum collection has to be this leopard skull mounted as an inkstand which was donated to the Royal College of Physicians’ ‘College Club’ by Sir Joseph Fayrer (1824–1907) in 1880. The skull had been collected by Fayrer on his famous trip to India accompanying the Prince of Wales in 1875–6, where he was tasked with protecting the heir to the throne from smallpox, cholera, and influence of the tropical sun. In 2018, we had the skull conserved for the first time – which led me down a path of research into the British Empire, tropical disease, taxidermy and big game hunting.

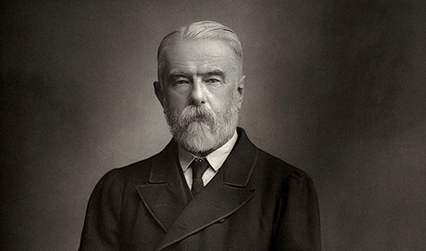

Joseph Fayrer was born at Plymouth in 1824 when his father, a Captain in the Royal Navy, was on his way home from a voyage to India. As was traditional of the period, Fayrer was trained to follow his father into the navy and service to the British Empire. At 16, he joined a fleet of mail packet steamers travelling to the West Indies, and spent his teenage years travelling around South America and the Caribbean. At 19, he decided to take up the study of medicine and returned to London to become a student at the Charing Cross School of Medicine. After completing his initial surgical training, he joined the navy as a surgeon and was eventually posted to India, where he famously survived the Siege of Lucknow in 1857. Taking a break from his Indian career, he gained his MD from Edinburgh and returned to India where he served as Professor of Surgery at Calcutta Medical College. Fayrer become a renowned expert on European health in India as well as the effects of snake venom on the human body. He was strongly convinced that all tropical diseases, including malaria, were the caused by Europeans being exposed to unfavourable environmental conditions, like cold winds, damp, rain or swampy air. He returned to Britain in 1872 and was appointed President of the India Office Medical Board and Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

By the 1870s, Fayrer was one of the most prominent ‘Anglo-Indian’ physicians in London; that is a British doctor with Indian experience. It is hardly surprising then that in 1875 Fayrer was approached by HRH the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) to accompany him on a trip to India. Using his expert knowledge, Fayrer was tasked with deciding when to travel, what to wear, which areas were safe to visit and to personally look after the Prince’s wellbeing throughout the journey. As Fayrer believed the tropical diseases were caused by the environment, he kept up a robust correspondence with contacts across India and the Mediterranean who updated on current temperatures, trends in the wind, and any local outbreaks of disease. More than anything, Fayrer feared the reports of cholera across Southern India – and his diaries of the trip attest to his deep anxiety that the Prince should fall fatally ill on his watch. The Prince, however, was a more adventurous sort – and constantly worried his doctor with his insistence on going out in the sun or remaining on deck when the nights turned cold.

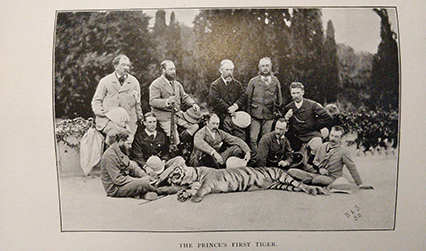

While the four-month long trip was intended to be diplomatic in nature – meeting local dignitaries, visiting hospitals, viewing factories and farms – the Prince had one thing in his mind: big game hunting. For British aristocrats, imperial lands like India offered a wealth of opportunity to hunt dangerous, exotic animals. In preparation for the trip, a taxidermist was appointed especially to prepare the spoils of their efforts for the return journey. Fayrer had been on numerous hunts himself during his Indian career, and brought his own special rifles. While the Prince is recorded as shooting at various birds, whales and sharks during his journey, the main aim of the trip was the much-coveted tiger hunt. Arriving in the Terai region of Northern India in February 1876, the Prince and his entourage spent several days hunting the big cats, mounted on elephants. In just one day, the group killed seven tigers, as well as numerous other animals like pheasant, deer, bears and pigs. Fayrer recorded tales from successful hunts in his diary:

The elephants soon told us that we were near a tiger, and almost immediately one passed near my elephant, growling; I could then have shot him easily. We were in a dense jungle at the time, which almost concealed him for a moment from the Prince’s view, but he had a shot and wounded him … the Prince fired twice and he lay dead. He was a fine, full-grown male tiger, 9ft. 6 in in length, with a grand head.

Since at least the 16th century, Indian elite had been hunting tigers in elaborate hunts. This tradition was taken up under the British Raj by European rulers and Indian princes- calculated to demonstrate power, wealth and dominance over the land. While this level of hunting is very troubling to us today, at the time tiger hunting was justified as a way of protecting local people and their livestock. At the end of the big hunting expedition, Fayrer recorded:

Packed all my things for a long journey to Lahore- light marching order- all I leave behind to be looked after by my companions. Guns are all to be packed, the shooting is over. The bag up to today is: 22 tigers, 1 cub alive; 2 leopards; 3 bears, 2 cubs alive.

Our leopard skull is undoubtedly one of these two leopards. Prepared for transport by the expedition’s taxidermist, the skull was likely separated from the skin which was probably made into a separate trophy. The skull was brought to renowned London taxidermy firm Rowland Ward on Fayrer’s return. The company was famous for transforming animals parts into animal parts like inkwells, umbrella stands and snuffboxes, sometimes known as ‘Wardian furniture’. The leopard-skull inkstand was then presented to the RCP’s ‘College Club’ – a social club of physicians founded in the mid-18th century. It is interesting that a leopard and not one of the more coveted tiger skulls was used for the inkstand. Perhaps they were all claimed for the Prince’s personal collection.

Now, over 120 year later, the skull was definitely looking its age. Used as a desk ornament for many years, the ink stand would have sat in various offices of the RCP – first at our Pall Mall East building and later at Regent’s Park. With noticeable bone loss and discolouration, I contacted Lucie Mascord, an accredited conservator specialising in natural history collections to assess the object. While the skull was undergoing treatment in her studio, we discovered that whatever the original taxidermist had used to clean and prepare the skull for its journey from India had resulted in a weakening of the bone. Over the years, it seems that the skull had been repeatedly painted white in an attempt to brighten its appearance. Teeth and bits of bone had been glued into place. The conservator was able to clean and stabilise the object – removing much of the old paint with a laser.

Natural history collections have very different conservation needs to medical equipment or artworks. We were very pleased to work with Lucie to give this fantastic object the attention it needed. While the inkwell might be unusual to find in a medical collection, it shows how closely entwined medicine was with empire in the 19th century.

Kristin Hussey, senior curator