In the current RCP exhibition, Ceaseless motion: William Harvey’s experiments in circulation, there is a mention in the timeline of William Harvey looking after the children of Charles I at the Battle of Edgehill in 1642. Knowledge of this event comes from the writings of 17th century chronicler, John Aubrey: ‘He told me that he withdrew with them [the Prince of Wales and Duke of York] under a hedge, took out his pocket book and read.’

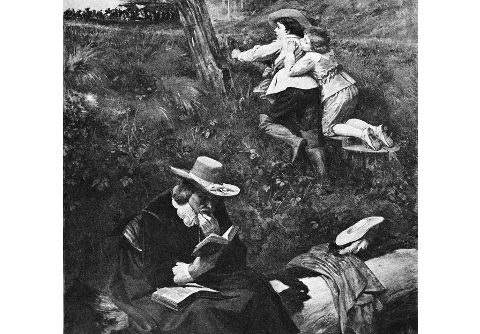

This account has led to less flattering regalings of the episode over the centuries, leading some to claim that Harvey simply hid under a hedge during the battle, and a rather damning 19th century painting by WF Yeames, showing Harvey sitting in a ditch, engrossed in his book and unmindful of his young charges, while the battle rages in the background. It has to be remembered that Harvey was already 64 in 1642, and therefore well beyond fighting age for the time, and was almost certainly involved in caring for the wounded in the aftermath of the battle. Nevertheless, thanks to Aubrey and Yeames, he will probably not be remembered among the bravest fellows in RCP history.

Examples of real bravery displayed by fellows, either under fire or in extremely perilous situations, abound in the oral history recordings. Since the institution of the Victoria Cross (VC) in 1856 army medical personnel have won twenty-seven VCs, and two out of the three awards of Bars (a decoration given to those winning two VCs), have gone to doctors. Although we haven’t yet interviewed anyone who has won a Victoria Cross we have certainly heard many stories of real valour.

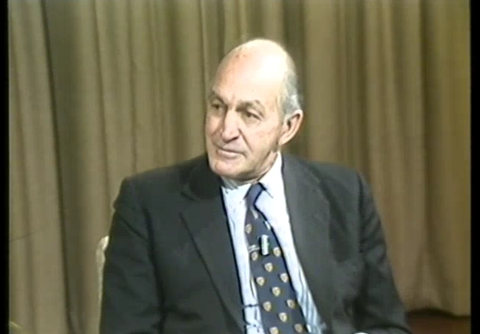

Sir Raymond Hoffenberg, well known for his fight against Apartheid in South Africa, was so determined to fight for the Allies in the Second World War that he left medical school at the age of 19 to join the South African Forces. He was under no obligation to do so, as there was no conscription in South Africa. In addition:

the recruiting officers would not accept me, as I had done three years of medicine, and they said I had to go back to medical school. My reply was that if I did go back I would not study and would not do my best in examinations, so there was no point.

He spent the next four years fighting in a tank division in North Africa and Italy.

Doctors in prisoner of war (POW) and concentration camps often had particular opportunities to help their patients and did so at great personal risk. RCP fellow, Ewa Raglan, talks of her mother’s endeavours to help Jews in a concentration camp near Warsaw in 1944. Her mother was a Polish medical student at the time, and later went on to work as a gynaecologist: ‘she was signing the death certification for Jewish live people to put them underneath of dead bodies to get them out of the camp.’

Archibald Cochrane and Bill Frankland, both medical officers in POW camps in WW2, speak of how they confronted camp officials to try and aid their patients. Cochrane recalls his actions after a spate of shootings in Salonika and a very high incidence of wet beriberi among prisoners:

I warned them [the Germans] that there was evidence of an absolute disaster and a very high death rate in this camp, which would be known about as it was bound to be written up after the war. And I asked for three things. I asked for the cessation of shooting, a large supply of yeast [to treat the beriberi] and a rapid evacuation of the camp into Germany where I understood the diets were very much better…. I remember that night I just went to bed and cried and cried. I didn’t believe the Germans would do it at all.

His bravery in confronting camp commanders saved many lives, as all three requests were met.

Fellows and members also carried out vital and dangerous work in refugee camps. RCP treasurer, Professor Chuka Nwokolo, recalls his father’s work running clinics during the Biafran War in Nigeria:

We were in Biafra for the three years of the war, and my father was the head of the refugee medical service, so we travelled. We lived in refugee camps where he ran clinics … I would have been twelve when the war started … My father would run clinics every morning for these long lines of refugees, and I remember being very much a part of that, being the runner, who went and got the tablets for the patients … During the war there were no lizards, as they’d all been eaten … and there were the bombs – we were being bombed regularly.

Dr Mark Rake, project volunteer and interviewee, also recalls leaving his young family and medical practice in London to go to Biafra for six months in 1970 to volunteer for the relief effort with the Red Cross.

To go back to Harvey, hiding under his hedge (or not) in 1642, it seems unlikely that we will ever know the full truth of this story. However, in terms of the courage needed to challenge the status quo, to question the teachings of his mentors and heroes, to pursue his theories through years of research and to stand up to the doubts of his peers, well, there’s no question that he had this kind of courage in abundance.

The exhibition Ceaseless motion: William Harvey’s experiments in circulation is open 9am–5pm, Monday–Friday, until 26 July 2018. Oral histories of RCP fellows are available via the Medical Sciences Video Archive and the RCP library catalogue.