Mud-based face-masks are a common modern-beauty treatment, and plenty of spas offer mud bath and other mud treatments. But I was quite surprised recently to find an eighteenth century book in the RCP library advocating the use of ‘soil or mould’ as a medical treatment for ‘all diseases, which are in their nature curable’.

A young Gentleman of [Newcastle], who had long tried in vain the medicines, advice, sea-bathing, &c. which are generally recommended for the cure of an obstinate scrophulous complaint, attended with swellings and ulcers in his glands and joints, and so great an inflammation and specks on his eyes, that he could not bear even the smallest degree of light, — and were continually gushing out with hot sharp water or corrupted matter, — was soon perfectly cured by going daily into the Earth, after he had gone through a course of my medicines, &c. without the desired effect.

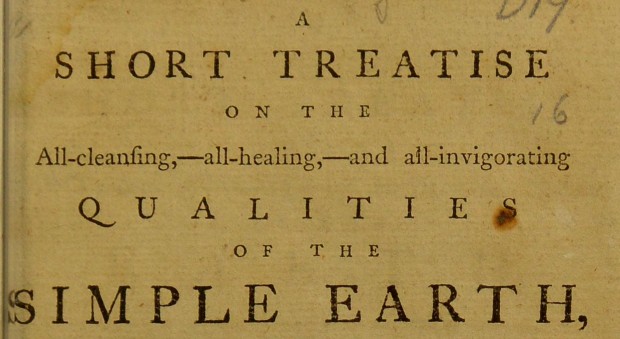

This claim was made by ‘Doctor’ James Graham (1745–1794), author of A short treatise on the all-cleansing, all-healing, all-vigorating qualities of the earth in 1790. Graham believed that the coldness, the ‘soapy moisture’, and the freshness of the earth were the cause of its therapeutic powers, the coldness removing ‘all morbid of preternatural heat’, the moisture extracting ‘all morbid humours’ and the freshness being imbibed into the human body in the same way that vegetables and trees are nourished by the earth. He recommended

immersing or placing the naked Human Body, up to the chin, or lips, or rather covered up over the head, but leaving the eyes and nose uncovered for feeing and breathing freely, in fresh dug up Earth, or in the Sand of the Sea-shore, for three, fix, or twelve hours at one time, and repeatedly.

Graham’s belief in the efficacy of earth-bathing was rooted in a belief that the earth was a ‘huge living system’ which could nurture all living beings. He himself gave some of his lectures buried up to the neck in soil, as described later by Henry Angelo:

After making his bow he seated himself on the stool ; when two men with shovels began to place the mould in the cavity ; as it approached to the pit of his stomach he kept lifting up his shirt, and at last he took it entirely off, the earth being up to his chin.

Graham studied medicine at Edinburgh University, taught by such notable physicians as Alexander Monro primus (1697–1767) and William Cullen (1710–1790). However, he didn’t finish his degree and never qualified as a licensed physician. During his life he worked in towns and cities across England and Scotland, as well as New York and Philadelphia in America, Paris, and the Isle of Man.

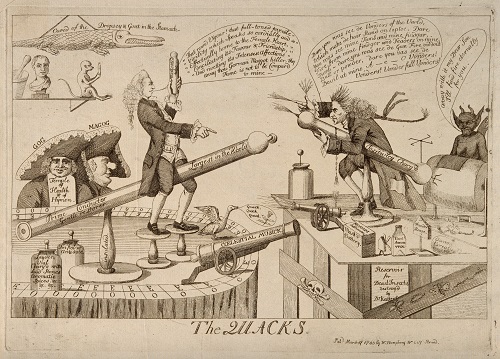

He became famous for the medical cures he developed and sold, which were attacked as being quack remedies but also won accolades from some. In general, he was in favour of a simple existence, opposing meat eating, excessive consumption and luxury of many kinds including soft beds and woollen clothing. He advised his patients to:

totally give up using the deadly poisons and weakeners of both body and soul, and the canker-worms of estates, called foreign Tea and Coffee, Red Port Wine, Spirituous Liquors, Tobacco and Snuff, gaming and late hours.

He was for many years interested in sexual virility, believing that vigorous sexual performance was key to healthy life. He supported the use of erotica as an aid to sexual performance, but disapproved of masturbation and prostitution.

He advertised treatments and cures for sexual difficulties and impotence, and built a medical cure centre which he called his Templum Aesculapium Sacrum (the sacred temple of Aesclepius, Greek god of medicine) in central London. The temple was furnished with elaborate and luxurious furnishings and decorations, including stained glass windows and perfumes, and fitted out with complicated equipment and apparatus including an ‘electrical throne’ and ‘celestial bed’. Married couples could spend a night in the celestial bed for the substantial fee of £50.

By 1780, Graham was a celebrity whose temple attracted crowds of visitors and who was mocked in contemporary plays such as The Genius of Nonsense. However, by 1781 he was already suffering debts, and had to scale the enterprise back. By 1783 Graham was in Edinburgh, arguing with the local authorities about the decency or otherwise of his lectures on sexual health and human reproduction, a dispute which landed him a short term in jail, before he was bailed and set off on a lecture tour around the country.

Though often treated by historians as a mere charlatan, in truth Graham was an enthusiast whose views, albeit carried to extremes, were actually highly typical of his age.

References

- Angelo H. Reminiscences. Vol 2. London: Coburn and Bentley, 1830. https://archive.org/details/reminiscenceswit02ange - accessed 9 November 2017.

- Graham, J.

- Porter, R. ‘Graham, James (1745–1794)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2005 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11199 – accessed 9 November 2017.

- Science Museum, ‘James Graham (1745-94)’ http://broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/people/jamesgraham – accessed 9 November 2017.