Thomas Willis, MD, was the son of Thomas Willis, of North Henxsey, near Abingdon, by his wife Rachel Howell, of an ancient family in Berkshire, and was born 27th January, 1621, at Great Bedwin, in Wiltshire. He was educated by Mr Edward Sylvester, a schoolmaster of some reputation in the parish of All Saints, Oxford, and in 1636 was entered at Christ church. He proceeded AB 19th June, 1639; AM 18th June, 1642; and about that time bore arms for the king.

He then devoted himself to the study of medicine, and took his degree of bachelor of medicine 8th December, 1646. Entering on the practice of his profession, he regularly attended the weekly market at Abingdon; took a house opposite Merton college, and at once appropriated one of the rooms to the performance of divine service. There Mr John Fell, afterwards dean of Christ church, whose sister Dr Willis had married, Mr John Dolben, afterwards archbishop of York, and Mr Richard Allistry, subsequently provost of Eton, read the liturgy, and administered the sacrament according to the rite of the church of England.

In 1660, shortly after the Restoration, Dr Willis was appointed Sedleian professor of natural philosophy, in place of Dr Joshua Cross, ejected; and on the 30th October of the same year (1660), was created doctor of medicine. He was one of the early fellows of the Royal Society, and was elected an Honorary Fellow of the College of Physicians in December, 1664.

In 1666 Dr Willis, on the invitation of Dr Sheldon, Archbishop of Canterbury, removed to London, and took up his abode in St Martin’s-lane. The reputation he had acquired at Oxford preceded him to town, and at once introduced him to an extensive and lucrative practice: “in a very short time,” says Wood,(1) “he became so noted and so infinitely resorted to for his practice, that never any physician before went before him, or got more money yearly than he.” Dr Willis, if not the regular physician to the Duke of York, afterwards James II, or to some members of his family, was certainly consulted on the state of health of the male children of that prince by his first wife, all of whom were, it seems, suffering more or less from disease originating in the amours of their father. Dr Willis spoke his mind freely, but by doing so gave great offence, and was never afterwards consulted. Bishop Burnet writes thus: “The children were born with ulcers, or they broke out upon them soon after, and all his sons died young and unhealthy. This has, as far as anything that could not be brought in the way of proof, prevailed to create a suspicion that so healthy a child as the pretended prince of Wales could neither be his, nor be born of any wife whom he had lived long. The violent pain which his eldest daughter had in her eyes, and the gout which early seized our present queen, are thought the dregs of a tainted original. Willis, the great physician, being called to consult for one of his sons, gave his opinion in the words, ‘mala stamina vitæ,’ which gave such offence that he was never called for afterwards.”

Dr Willis died at his house in St Martin’s-lane, 11th November, 1675, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. His monument bears the following inscription:-

Siste, properes licet quisquis es, Viator

Ne posthac doleas te tanti viri sepulchrum imprudentem præteriisse

Cujus forsan beneficio debetur quod ipse ad sepulchrum

nondum perveneris.

Magnus hoc tumulo Willisius conditur:

Celeberrimus ille Thomas Willisius, MD

ex Æde Christi Philosophiæ naturalis

in florentissima Oxoniensi Academia Professor, et non tantum

Carolo II do Rege sed et Europæ universæ,

Princeps Medicus.

Cujus laudes sane non capit sepulchrale marmor

Quibus orbis ipse vix sufficit.

In Arte Medica et Philosophia naturali

Exercenda, excolenda, promovenda quantopere inclaruerit

Norunt omnes tum exteri quam nostrates

Alterum testabuntur morbi innumeri mirum in modum profligati.

Alterum arte non mediocri facta experimenta

Utrumque doctissimæ ipsius lucubrationes hodie attestantur

Neque minus in pietate fuit insignis quam ingenio et eruditione.

Regi in nequissimis temporibus fidelis

Ecclesiæ etiam oppressæ obsequentissimus,

Quam non modo affectu dilexit, sed munificentiâ locupletavit

Fortunâ adversâ inconcussus:

Affluente eximie temperans.

In summâ doctrinæ gloriâ humilis et modestus.

Pecuniâ erogandâ in pauperes effusissimus

In suorum gratiam, frugi et providus

In se solummodo parcus.

Labori et vigiliis (heu! nimis) indulgens;

Quibus factum est ut aliorum vitam producendo suam

contraxerit

E vivis enim excessit pleuritide confectus

Anno Atatis 53.

Nati Christi, 1675.

“He left behind him,” says Wood, “the character of an orthodox, pious, and charitable physician; and some years before his death he had settled a sum on the church of St Martins-in-the-Fields, for the daily reading of prayers early and late to such servants and people of the parish who could not, through multiplicity of business, attend the ordinary service.” “Though Willis was a plain man,” continues Wood, “a man of no carriage, little discourse, complaisance, or society, yet for his deep insight, happy researches in natural and experimental philosophy, anatomy, and chemistry, for his wonderful success and repute in his practice, the natural smoothness, pure elegancy, delightful unaffected neatness of Latin style, none scarce have equalled, much less outdone him how great soever.” It is admitted, however, that Dr Willis’s method of procedure in his inquiries and in his writings was unfortunate for his reputation. Instead of busying himself in observation and experiment, he was exercised in framing theories. “Hence it is,” says Hutchinson,(2) “that, while his books show the greatest ingenuity and learning, very little knowledge is to be drawn from them, very little use to be made of them; and perhaps no writings which are so admirably executed and prove such uncommon talents to have been in the writer, were ever so soon laid aside and neglected as the works of Dr Willis.”

Dr Willis’s writings are as follows:

Diatribæ duæ Medico-philosophicæ, quarum prior agit de Fermentatione sive de motu intestino particularum in quovis corpore; altera de Febribus sive de motu earundem in sanguine animalium. Hagæ Comitis, 1659; to which was appended, Dissertatio Epistolaris de Urinis.

Cerebri Anatome Nervorumque descriptio et usus. Lond. 8vo. 1664. With which was printed, De Ratione Motûs Musculorum.

Pathologiæ Cerebri et Nervosi Generis Specimen; in quo agitur de Morbis Convulsivis et de Scorbuto. Oxon. 4to. 1667.

Affectionum quæ dicuntur Hystericæ et Hypochondriacæ Pathologia Spasmodica, vindicata contra Responsionem epistolarem Nath Highmore, MD Lond. 4to. 1670. To which were added, Exercitationes Medico-Physicæ duæ: 1. De Sanguinis Ascensione: 2. De Motu Musculari.

De Animâ Brutorum, quæ Hominis vitalis ac sensitiva est, Exercitationes duæ; prior Physiologica, ejusdem naturam, partes, potentias et affectiones tradit; altera Pathologica, morbos qui ipsam et sedem ejus primariam nempe Cerebrum et Nervosum Genus afficiunt, explicat; eorumque Therapeias instituit. Oxon. 4to. 1672.

Pharmaceutice Rationalis; sive Diatriba de Medicamentorum Operationibus in Corpore Humano. Oxon. 1674.

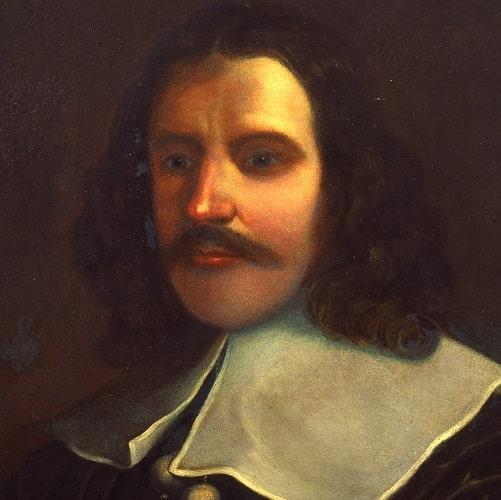

Most of the above have been translated into English, and Willis’s collected works have been several times published. The Amsterdam edition, by Professor Blasius, 4to. 1682, is incomparably the best. Dr Willis’s portrait, by Vertue, was engraved by Knapton.

William Munk

[(1) Athenæ Oxon, Vol.ii, p. 402.

(2) Biographia Medica, 2 vols. 8vo. Lond. 1799. Vol. 2, p. 484.]