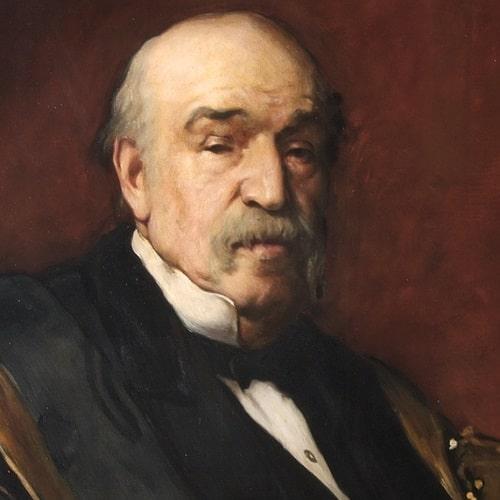

William Jenner was born at Chatham, the fourth son of John Jenner, an innkeeper, and his wife Elizabeth, daughter of George Terry. His medical education took place at University College, London, and he was apprenticed for a time to a surgeon in Marylebone. After qualifying in 1837, he began to practise in the same area and received an appointment as surgeon to the Royal Maternity Charity, Finsbury Square. His studies continued, and, after taking his M.D. degree in 1844, he gave up general practice in favour of a consultant’s career. The foundations of his success were truly laid when he published in 1850 a small volume with the title On the Identity or Non-Identity of Typhoid and Typhus Fevers, the result of two years’ patient enquiry into cases of "continued fever" at the London Fever Hospital, which finally established the separate identity of the two fevers. His work had already led to his appointment, a year earlier, as professor of pathological anatomy at University College and assistant physician to University College Hospital, and in the next three decades he held the offices of Holme professor of clinical medicine (1860— 63) and professor of medicine (1863-67), full physician (1854-78), with charge of the skin department after 1856, and consulting physician (1879-98). He was also physician to the Hospital for Sick Children from its foundation in 1852 till 1862 and to the London Fever Hospital from 1853 to 1861, and consulting physician to the German Hospital and Hospital for Diseases of the Throat.

In 1861 Jenner’s appointment as Physician-Extraordinary to Queen Victoria began a long and close association with the Royal Household. He attended the Prince Consort during his fatal attack of typhoid in that year and ten years later treated the Prince of Wales when he lay ill with the same fever. He became Physician-in-Ordinary to the Queen in 1862 and received the same appointment from the Prince of Wales a year later. He was created a baronet in 1868, K.C.B. in 1872 and G.C.B. in 1889. He was also a Commander of the Belgian Order of Leopold. He became an F.R.S. in 1864.

From his own profession, too, he received the highest honours. President of the Epidemiological Society in 1866-68, of the Pathological Society in 1873-75 and of the Clinical Society in 1875, he was in 1881 and in the next six years elected to the presidency of the Royal College of Physicians, where he had already served as Censor and delivered the Goulstonian Lectures (1853). His term of office witnessed such developments as the institution of the Conjoint Examining Board and the Diploma in Public Health and the passing of the Medical Act of 1886.

Jenner, at the height of his powers, was the undisputed leader of his profession, and he owed his supremacy to his mastery in two of its departments — those of the practising consultant and of the clinical teacher. Although, at different stages of his career, a specialist in diseases of the heart, abdomen and skin, in fevers, rickets, tuberculosis, diphtheria and emphysema, he was essentially a general physician who could call to his aid in diagnosis and treatment a vast and wide experience of every branch of medicine, Nor, while paying the most thorough attention to detailed observation, did he despise such laboratory tests as were available, or neglect to follow up cases by post-mortem examination.

"The great aim of the physician is to prevent disease; failing that, to cure; failing that, to alleviate suffering and prolong life." With these objects in mind, Jenner drove home, in language dogmatic, forceful and unadorned, the lessons of his own experience to generations of students. Much of his teaching was published in two volumes of Lectures and Essays and Clinical Lectures in 1893 and 1895 respectively. Jenner’s curtness of manner, his directness of speech, caused his first Court appointment to be greeted with surprise. In later years, he was inclined to take umbrage easily and to show little tolerance for other opinions. But such traits only accentuated the sterling honesty of his own opinions.

Jenner’s capacity for hard work — witnessed by his fortune of £375,000 — left him little time or inclination for amusements, although he would while away long journeys by reading cheap novels. He was a non-smoker and almost a teetotaller but inordinately addicted to drinking cups of tea. After retiring in 1889, Jenner lived in Hampshire, and he died at Greenwood, near Bishop’s Waltham. He married in 1858 Adela Lucy Leman, daughter of Stephen Adey, and had five sons and a daughter.

G H Brown

[Lancet, 1898; B.M.J., 1898; Times, 13 Dec. 1898; Daily Telegraph, 13 Dec. 1898; D.N.B., 1st Suppl., iii, 37]