Rodney Harris was professor of medical genetics and director of the department of medical genetics, University of Manchester. His career spanned a period of rapid expansion and innovation in the discipline. He was born in Liverpool, the son of Ben and Tessa Harris. His parents clearly had ambitions for him: he was named after Rodney Street, the medical street in Liverpool. During the Second World War, the family, who were from an immigrant Jewish background, moved constantly to avoid the bombs, narrowly escaping disaster when their house on the Wirral suffered a direct hit. Finally, the family lodged in a house just under the quarry in Penmaenmawr. In this Welsh-speaking community they were called ‘the Chinese’. His father joined the RAF and later resumed his occupation as a jeweller. Rodney worked with him during vacations, providing him with a lifelong appreciation of jewellery. After passing the 11-plus at the second attempt, he went to John Bright Grammar School, Llandudno. He described inspirational tuition from the biology master and botany mistress, supplemented by many hours spent alone in the town library. One year at Quarry Bank Grammar School in Liverpool completed his schooling.

He was totally deaf from birth in the left ear and suffered chronic infections in the right ear, causing severe, later profound, hearing loss. He spent a year at Liverpool University’s dental school and then applied to the dean to transfer to medicine. Advised that this might be possible with a good intercalated BSc, he was fortunate to choose anatomy. There he was guided by R G Harrison and, after achieving a first class honours degree, secured a place at the medical school. Deafness made clinical medicine difficult and on the first occasion the rigors of the MRCP proved too challenging when asked to interpret heart sounds and percuss an abdomen. At this time he was inserting a pledget of cotton wool over a large perforation that compacted in the inner ear obscuring the oval window. His great friend Philip Stell referred him to Blackpool for pioneering surgery to provide a tympanic membrane graft.

Following house jobs, he completed a diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene, receiving the Warrington Yorke medal, and left for the Niger Delta to study children with G6PD deficiency and falciparum malaria. This work gained him an MD. He was accompanied by his first wife Ruth, a nurse who went to Britain in 1939 as a refugee on the Kindertransport. Later he went to South West Africa as a Darwin research fellow to study the genetics of skin colour in Yellow Bushmen.

In Liverpool, he was appointed to Cyril Clarke’s [Munk’s Roll, Vol.XI, p.112] department to continue research and then went to Leiden to study the genetics of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system. This work continued with Jean Dausset in Paris. In 1967, he was offered the post of reader in medical genetics by Douglas Black [Munk’s Roll, Vol.XI, p.62] in Manchester and to set up tissue typing for renal transplantation. As consultant physician he had four medical beds, but found that a noisy ward precluded consultation and conversation. His work focused on research and he lectured widely in the UK and abroad, confessing to answering the questions he hoped he’d been asked as he rarely heard those from the audience.

As developments in medical genetics impacted on many branches of medicine, he used his energy and redoubtable political skills, combined with a clear vision of NHS service development, to create a strong foundation in this emerging discipline. Special medical development funding was provided to establish genetic centres in Manchester, Cardiff and the Institute of Child Health, London, which led to the development of molecular genetic testing and promoted integration of clinical and lab genetics ‘under one roof’. The first MSc course in genetic counselling was established in Manchester and graduates now work in departments of medical genetics in the UK and abroad.

Despite increasing deafness, he chaired the specialist advisory committee in clinical genetics, the Royal College of Physicians’ clinical genetics committee, was president of the Clinical Genetics Society and consultant adviser in genetics to three chief medical officers.

One of his happiest times was in 1984 when he spent a sabbatical at St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington with Bob Williamson during the race to isolate the gene for cystic fibrosis. Resident at 10 St Andrews Place, next door to the Royal College of Physicians, he was often seen walking the housekeeper’s dog in Regent’s Park.

Following Ruth’s early death in 1975, he married Hilary, a GP who assisted with many published studies on the role of primary care in delivering genetic services. In 1996, he was awarded a CBE for services to medicine. Following his retirement in 1997, he worked for five years as project leader and author of an EU-funded project, Concerted Action on Genetic Services in Europe, in 17 European countries. This led to the recognition of medical genetics as a specialty in a number of European countries.

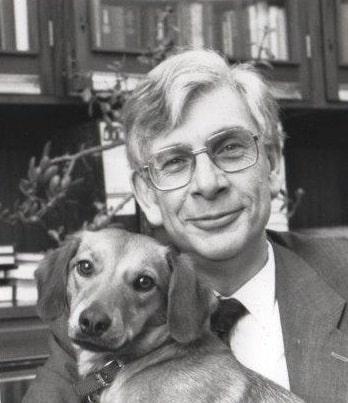

Struggling throughout his career with deafness, in 1990 he was fortunate to get a trained hearing dog, who was his constant companion for 17 years and helped with the problems of isolation; Jodie’s jacket was a visible reminder of an often hidden disability. Finally, at the age of 81, he had a successful cochlear implant performed by Richard Ramsden. Although his long retirement was marred by illness and disability, he found time to read his extensive library of modern history.

He died from cerebrovascular disease at home in Knutsford, Cheshire, and was survived by his wife, Hilary, and three children – Alexandra, a dermatologist, Richard, a pharmacist (now a gardener), and Anne, who has a degree in English.

Alexandra Harris