Richard Warren, M.D. was born on the 13th December, 1731, and was the third son of the Rev. Dr. Richard Warren, archdeacon of Suffolk, and rector of Cavendish in that county, a divine of great eminence and an accomplished scholar, one of the antagonists of bishop Hoadley in the controversy respecting the eucharist, and the editor of the Greek commentary of Hierocles upon the Golden Verses of Pythagoras. The younger Warren was educated at the grammar school of Bury St. Edmund’s, whence, in the year 1748, immediately after his father’s death, he removed to Jesus college, Cambridge. Warren was one of those rare characters which distinguish themselves equally during the period of education and in the more trying scenes of mature life. At this moment his means of support were scanty, and the prejudices which then prevailed among certain members of the university were not calculated to encourage or smooth the progress of the son of an able Tory. Young Warren, however, overcame every difficulty of his position, and his name was fourth on the list of wranglers in the year of his degree 1752. He was elected to a fellowship of his college—he obtained the prize to middle bachelors for Latin prose composition, and the following year that for senior bachelors. On obtaining his fellowship at Jesus college the church naturally offered itself as his profession, but his inclination was for the law. Whilst in this state of doubt, the son of Dr. Peter Shaw, an eminent London physician, was entered at Jesus college, and placed under his tuition. The acquaintance thus formed determined his lot in life, for the talents of the tutor were not lost on Dr. Shaw, who soon took a warm interest in his pursuits, strongly recommended him to pursue the study of medicine, and predicted that should he do so he would rank with the first physicians of his country. Finally, in proof of his esteem and affection, Dr. Shaw gave him the hand of his daughter Elizabeth in 1759. He proceeded A.M. 1755; M.D. 3rd July, 1762; was admitted a Candidate of the College of Physicians 30th September, 1762; and, having produced the warrant by which he was made physician in ordinary to the king, a Fellow, 3rd March, 1763. He delivered the Gulstonian lectures in 1764, and the Harveian oration in 1768; was Censor in 1764, 1776, 1782; and was named an Elect 9th August, 1784. On the 5th August, 1756, having at that time a licence ad practicandum, from the university of Cambridge, he was elected physician to the Middlesex hospital, and on the 21st January, 1760, physician to St. George’s hospital; the former appointment he resigned in November, 1758, the latter in May, 1766.

Dr. Warren’s progress as a physician was unusually rapid. Not only had he the influence and recommendation of his father-in-law Dr. Shaw to advance his interests, but those also of Sir Edward Wilmot. Shortly after he commenced practice, Sir Edward, then physician to the court and much employed among the nobility, was in attendance on the princess Amelia, daughter of George the Second. Sir Edward, then advanced in years and looking to retirement, proposed Dr. Warren as an assistant, to attend to the more minute and arduous duties required by the princess, who was subject to sudden seizures that created alarm. At the commencement of his professional career, Dr. Warren, during three summers, went to Tunbridge Wells, and on two of these occasions her royal highness visited that watering place under his care. On the retirement of Sir Edward Wilmot, Dr. Warren continued physician to the princess, and one of the rewards bestowed upon him was the appointment of physician to George III, which was procured for him by her royal highness’ influence on the resignation of his father-in-law, Dr. Shaw. " Dr. Warren’s eminence is not to be ascribed, however, to mere patronage, nor to singularity of doctrine, nor to the arts of a showy address, nor to any capricious revolution of Fortune’s wheel; it was the just and natural attainment of great talents These talents, indeed, cannot be subjected to the scrutiny of literary criticism, because he was too eagerly engrossed by pressing occupations to find leisure sufficient to commit many of his observations to paper; but the accuracy of his prognosis, and his fine sagacity, survive in the recollection of a few. His ready memory presented to him on every emergency the extensive stores of his knowledge; and that solidity of judgment which regulated their application to the case before him would have equally enabled him to outstrip competition in any department of science and art. He was one among the first of his professional brethren who departed from the formalities which had long rendered medicine a favourite theme of ridicule with the wits who happened to enjoy health.

He was one of the few great characters of his time whose popularity was not the fruit of party favour. Without any sacrifice of independence he gained the suffrages of men of every class, as well as the more difficult applause of his own fraternity. He enjoyed the friendship of many distinguished men, and among others of lord North; his conversation, indeed, was peculiarly fitted to conciliate every variety of age and of temperament. The cheerfulness of his own nature, and the power which he possessed of infusing it into others, enabled him to exercise over his patients an authority very beneficial to themselves; and in this respect, as in some others, he has left an instructive example to future professors of medicine, who perhaps do not always sufficiently seek to inspire the objects of their care with a train of animating thoughts. Warren arrived early at the highest practice in this great metropolis, and maintained his supremacy to the last with unfading faculties. The amount of revenue sometimes enters into the computation of a medical character, and such anecdotes perhaps form a link in the domestic history of the profession. He is said to have realised 9,000l. A year from the time of the regency, and to have bequeathed to his family above 150,000l."(1) If posterity should ask what works Dr. Warren left behind him worthy of the great reputation he enjoyed during his lifetime, it must be answered that such was his constant occupation in practice among all classes of people, from the highest to the lowest, that he had no leisure for writing, with the exception of a very few papers published in the College Transactions. But the unanimous respect in which he Was held by all his medical brethren, which no man ever obtains without deserving it, fully justifies the popular estimate of his character. To a sound judgment and deep observation of men and things he added various literary and scientific attainments, which were most advantageously displayed by a talent for conversation that was at once elegant, easy, and natural.

Of all men in the world, he had the greatest flexibility of temper, instantaneously accommodating himself to the tone of feeling of the young, the old, the gay, and the sorrowful. But he was himself of a very cheerful disposition, and his manner being peculiarly pleasing to others, he possessed over the minds of his patients the most absolute control ; and it was said with truth, that no one ever had recourse to his advice as a physician, who did not remain desirous of gaining his friendship and enjoying his society as a companion. In interrogating the patient he was apt and adroit; in the resources of his art, quick and inexhaustible; and when the malady was beyond the reach of his skill, the minds of the sick were consoled by his conversation, and their cares, anxieties, and fears soothed by his presence. And it may be mentioned among the minor qualities which distinguished Dr. Warren, that no one more readily gained the confidence, or satisfied the scruples of the subordinate attendants upon the sick by the dexterous employment of the various arguments of encouragement, reproof, and friendly advice.(2) The height Dr. Warren had rapidly attained in his profession he maintained with unabated spirit till his death, which took place at his house in Dover-street on the 22nd June, 1797(3); his disease was erysipelas of the head, which destroyed him in his sixty-sixth year, at the very time when the most sanguine hopes were entertained of his recovery by sir George Baker and Dr. Pitcairn. His widow, two daughters, and eight sons survived him. He was buried at Kensington church, where a tablet to his memory is thus inscribed:—

Richardo Warren,

apud Cavendish in agro Suffolciensi nato,

Collegii Jesu Cantab. Quondam socio,

Regis Georgii Tertii medico,

Viro ingenio prudentiâque acuto,

Optimarum artium disciplinis erudito,

Comitatis et beneficentiæ laude bonis omnibus commendatissimo;

qui medicinam feliciterque Londini factitavit.

Decessit x Kalend. Jul.

Anno Christi MDCCXCVII.

Ætat. Suæ Lxvii.

Elizabetha uxor et liberi decem superstites

H.M. faciendum curaverunt.

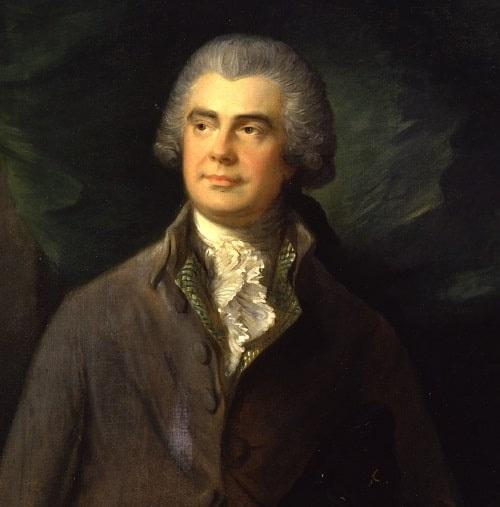

Two papers from Dr. Warren’s pen are to be seen in the "Medical Transactions." His portrait, by Gainsborough, is in the College. It has been engraved by I. Jones. It was presented by his son, Pelham Warren, M.D., on the opening of the College in Pall Mall East in June,1825.

William Munk

[(1) Dr. Bissett Hawkins’ Memoir of Dr. Warren, in Lives of British Physicians, p. 232.

(2) The Gold Headed Cane. 2nd Edn. 8vo. Lond. 1728, p. 205, et seq.

(3) "Ecquis erat unquam scientiâ morborum locupletatus magis, vel magis curatione exercitatus; ecquis erat unquam qui suavi illâ sermonis et morum humanitate, quæ in ipso remediorum loco haberi potest, ecquis erat unquam qui Warrenum superabat? Erat illi ingenii vis maxuma, perceptio et comprehensio celerrima, judicium acre, memoria perceptorum tenacissima. Meministis, Socii, quàm subtiliter et uno quasi intuitu res omnes ægrotantium perspiceret penitus et intelligeret! In interrogando quàm aptus esset et opportunus, quam promptus in expediendo! Omnia etenim artis subsidia statim illi in mentem veniebant, et nihil ei novum, nihil inauditum videbatur. In eâ autem facultate quâ consolamur afflictos et deducimus perterritos a timore, quà languidos incitamus, et erigimus depressos, omnium Medicorum facile princeps fuit: et si qui medicamentis non cessissent dolores, permulcebat eos, et consopiebat hortationibus et alloquio.

...Stetit urna paulum

Sicca, dum grato Danai puellas

Carmine mulcet.

"Verum ea est quodammodo artis nostræ conditio, ut Medicus, quamvis sit eruditus, quamvis sit acer et acutus in cogitando, quamvis sit ad præcipiendum expeditus, si fuerit idem in moribus ac voluntatibus civium suorum hospes, parum ei proderit oleum operamque inter calamos et scrinia consumpsisse. Warrenus autem in omni vitæ et studiorum decursu, si quis unquam alius, Pallade dextra usus est, atque omnium quibuscum rem agebat mentes sensusque gustavit; et quid sentirent, quid vellent, quid opinarentur, quid expectarent arripuit, percepit, novit. Tantam denique morum comitatem et facilitatem habuit, ut nemo eo semel usus esset medico, quin socium voluerit et amicum."—Oratio Harveiana, Anno MDCCC. Habita, auctore Henrico Halford, p. 12]