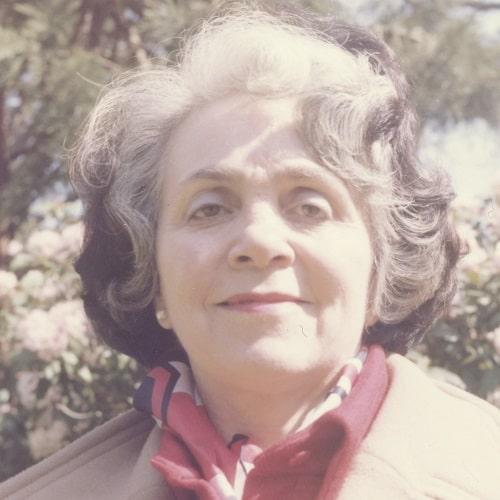

Jean Ginsburg, a reproductive endocrinologist of international repute, was a great enthusiast for medicine, music and life's pleasures. Her father, Naum Ginsburg, was a civil engineer who sheltered Trotsky when he was on the run from the Tsarist troops and was also among those who greeted Lenin off his train when he arrived back in Russia to start the 1917 revolution. Her mother, Anya Bielenky, was a pianist who had studied at the Conservatoire in St Petersburg under Glasunov. Jean's parents fled to London in 1921. Soon after, her older brother, David, who was later to become the Labour MP for Dewsbury North, was born.

Jean came from a medical family. A great-aunt was reputedly the first woman dentist in Russia. Jean's aunt Evgenia qualified as a doctor in Montpelier before the first world war and another aunt, Charlotte, and uncle, Dodya, became GPs in London.

Jean won a scholarship from St Paul's School to Somerville College, Oxford, to read medicine, becoming one of the first women to qualify from St Mary's Hospital, Paddington. Her initial research career was at St Thomas's Hospital, where she used forearm venous occlusion, plethysmography, then a new means of measuring blood flow in the limbs, to study change in the circulation during pregnancy and the menopause. In 1966, she moved to the newly established department of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Royal Free Hospital, where she helped set up a gynaecological endocrine service. At that time scientific reproductive endocrinology was in its infancy.

It was very much to her credit and indeed typical of her attitude to women's problems that she was instrumental in setting up one of the first, if not the first, clinic for the menopause in the UK when part of the Royal Free Hospital was located at New End. She provided a clinical service for menopausal women at a time when there was relatively little therapy available for the treatment of climacteric. She demonstrated clearly, using very simple basic circulatory techniques, that the menopausal hot flush was essentially a reflex phenomenon not an emotional reaction and that it reflected a disturbance of thermoregulatory mechanisms. In the late sixties and early seventies, when urinary gonadotrophins became available for use in female reproductive disorders, she established the first ovulation induction programme. This is an interest which continued more or less up until the time of her retirement. She published over 250 peer reviewed articles, wrote one book The Circulation in the female: from the cradle to the grave (London, Parthenon, 1989) and also co-edited Drug therapy in reproductive endocrinology (London, Arnold, 1996) and Sex steroids and the cardiovascular system (London, Parthenon, 1998). After the retirement she committed much time to medico-legal work.

She attracted numerous scientific workers who came to study under her to learn her techniques and understand how to treat menopausal women. She was tireless, despite her three young children and domestic responsibilities, as well as having been involved in a devastating traffic road accident in 1968. Indeed her injuries were so severe that she was told at that time that she might never walk again. She proved experts wrong and returned to work in plaster, lecturing to students while still convalescent.

Jean was an exceptional person, fiercely individualistic and she had an insatiable appetite for work. She carried out her research activities until the end of her life. It is said that one 'experienced her' rather than 'knew her'. Colleagues were often struck by her incisive intelligence. She recognised well before the advent of computers the benefit of establishing accurate data. Indeed, one of her greatest achievements was her meticulous and imaginative record keeping on every patient who attended her clinic. Her data base, which stretches back to 1966, is still used in ovarian cancer research today.

Jean was well read, fluent in French and spoke and understood some Russian and German. She was also a talented pianist. After her retirement from NHS she took up the piano again, which brought her a great deal of happiness in the last years of her life. She had many other interests outside medicine and lived her life to the full. She was a frequent attendee at Glyndebourne, the Royal Opera House and Wigmore Hall. Jean loved travelling and enjoyed fine wines, the benefits of which she never ceased to advocate.

She will be remembered best, however, for her work, which put her at the forefront of the use of gonadotrophins in female reproductive disorders. She is survived by her husband, Jack Henry, a former Reuters editor, their daughter, two sons and three granddaughters, whom she adored. A charity, the Jean Ginsburg Memorial Foundation, has been established in her memory and will provide funding for students of her two great passions - medicine and classical piano.

Gordana Prelevic

[Brit.med.J.,2004,328,1321;The Times 12 May 2004;The Guardian 14 June 2004]