Eluned (Lyn) Woodford-Williams was born in Liverpool, the eldest of four daughters. Her father, John Woodford-Williams, was a dental surgeon and her mother, Edith Mary Stevens, was the daughter of a horticulturist. From her Lyn inherited her interest in gardening, especially fruit and rose growing. Her father had always wanted his first born to be a son and it is possible that Lyn’s great drive to succeed in medicine sprang from this fact.

Lyn began her education at Liverpool College, but the family moved to Wales and she attended the Cardiff High School for Girls. Always keen to become a doctor, she entered the Welsh National School of Medicine, where she obtained a BSc in 1933. She moved to London to University College Hospital for her clinical years, qualifying in 1936 and becoming house physician to Sir William Pearson. Her first interest was in children and she went on to become RMO at the Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool, obtaining the DCH in 1938. She then returned to University College Hospital as house physician to Sir Thomas Lewis [Munk’s Roll, Vol.V, p.531] who, she was proud of telling her friends, diagnosed the mitral valve disease, from which she was to die almost half a century later.

In 1939 she became RMO to Redhill Hospital, Surrey. While holding this post she obtained the DRCOG, the MRCP and the London MD, with gold medal in medicine, all in the same year, 1940; the year of the Battle of Britain and the air raids on London.

In 1942 she moved to Manchester Royal Infirmary as chief assistant to T H Oliver [Munk's Roll, Vol.V, p.312], and became for a time temporary assistant physician to the Manchester Northern Hospital.

She married Dennis Astley Sanford in 1939, who also became MRCP in 1940. He subsequently became a surgeon and, after the war, was appointed to a consultant post in Sunderland. Lyn moved there with him. She had two young children and for a time had no regular appointment. But in 1950 Oscar Olbrich arrived in the town with revolutionary ideas about the way to run a geriatric service, and she became his first senior registrar and then his first assistant physician. She assisted him not only to develop the service but also to pursue his researches.

Olbrich, a refugee from Austria, spent the war in Edinburgh where he developed the idea that old people required the same high standards of medicine as were offered to younger people, and that if this were done many might escape joining the ranks of the chronic sick. He also believed in research into the problems of old age. One of his first acts when he inherited 600 chronic sick beds in Sunderland was to establish a research laboratory to study renal function in the elderly. Olbrich was a creative genius but he was also a tyrant in the mould of the continental professor. He was devoted to Lyn, but he abused her unmercifully, and in public. He always called her ‘Villiams’, never by her Christian name. ‘Villiams, you fool’, spoken in a teutonic accent, was something heard more than once in the wards. But when he had a heart attack he would have no one to attend him but Lyn.

When Olbrich died, Lyn was the obvious person to succeed him, and the Sunderland unit went from strength to strength under her direction. Lyn worked all hours, but in addition found time to serve as a JP. She established the first day hospital in the north of England, and published papers about it which are still quoted. Sunderland rapidly gained an international reputation for geriatric medicine. In the early years of the NHS it was one of only two or three units in Britain which could present geriatric medicine as an exciting form of medical practice with a great future. The unit attracted many trainees and she took pains to place them in good jobs. The people that she trained have developed geriatric services around the country and proved the validity of the Sunderland philosophy. She was proud of them.

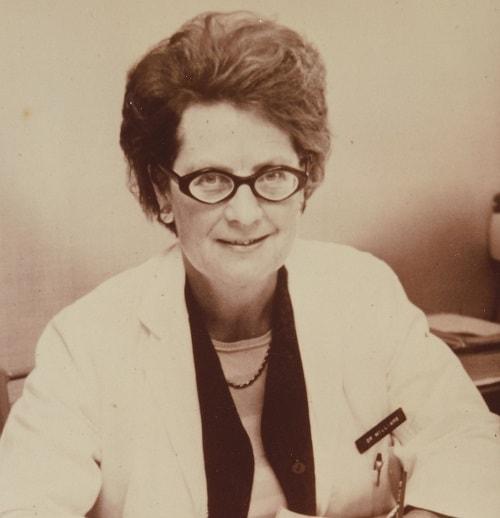

One of her achievements was to establish geriatric medicine as an age related discipline. In Sunderland all medical emergencies in patients over 65 went to her department. She had more beds than all the general physicians put together, and insisted on the highest standards of medicine. She even developed her own coronary care unit. Bernard Isaacs recalls seeing Lyn sitting besides a hugh pile of case notes representing the week’s discharges, reviewing them in the presence of her staff and pouncing on any errors or omissions. He added ‘...she required in her staff the same pace of work she demanded in herself. Her then senior registrar told me that if he wanted to get his hair cut, he had to take a week’s holiday.’ Her intensity was somewhat daunting, and when she peered at you through her glasses it could be a frightening experience.

As well as drive, Lyn had courage. In 1958 the new European Clinical Section of the International Association of Gerontology, having elected Olbrich as secretary, planned to hold a meeting in Sunderland. Soon after his election Olbrich died suddenly, and the entire responsibility for organizing an international meeting in what had lately been a workhouse, in a town which had never before held more than a local medical meeting, fell on Lyn’s shoulders. The light burned in her office far into the night. Needless to say, the conference was a great success and launched Lyn on an international career. She knew everyone in Europe, on both sides of the iron curtain, who was interested in gerontology, and became, with Norman Exton-Smith, co-editor of the new international journal Gerontologia Clinica.

In 1973 she was appointed to the directorship of the Health Advisory Service, a post which she held with distinction for five years and which she regarded as the pinnacle of her career. She was one of the few doctors to get on well with Barbara Castle, at that time Minister for Social Services. This helped her to affect government policies in ways which assisted the development of geriatric medicine. Through her influence many local geriatric services were improved, and her contributions as a speaker at King Edward’s Fund courses helped to spread knowledge of good management in geriatric medicine and psychiatry.

Her concern for the development of the psychiatry of old age was recognized by the award of the MRCPsych in 1978 and the FRCPsych in 1983. During this time she was a regular attender at meetings of the College’s section for the psychiatry of old age. There are plenty of psychiatrists among the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, but there are very few physicians among the Fellows of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, a fact which gave her great pleasure.

Within our own College Lyn also made her mark. With her UCH connexions, she was friendly with Max Rosenheim [Munk's Roll, Vol.VI, p.394] as well as with Norman Exton-Smith, and with their help and encouragement persuaded Comitia to establish a geriatrics committee within the College. She would have been delighted that within a year of her death the College had established a Diploma in Geriatric Medicine.

After her time at the Health Advisory Service, which was rewarded by a CBE, she went for a year back to Manchester to stand in as professor of geriatric medicine while Brocklehurst was in Canada. Her power to transmit enthusiasm for geriatric medicine once again made its mark.

Lyn then retired to her cottage at Abersoch in Wales. She loved the Welsh mountains and Welsh culture. She was a regular supporter of the National Eisteddfod. She acquired many paintings by modern Welsh artists, which she bequeathed to the National Museum of Wales. Her retirement was marred by ill health and by loneliness, her marriage having broken up at about the time she went to the Health Advisory Service. She survived an attack of bacterial endocarditis, but eventually her heart failed. At the very end Dennis reappeared in her life and took her to Sunderland, where she died peacefully. She was survived by a son and a daughter, both medically qualified. Her son John became a member of the College and followed his mother as a consultant in geriatric medicine, a ‘first’ of which she was naturally very proud.

Norman Exton-Smith summed her up well in his BMJ obituary: ‘Lyn directed indefatigable energy towards all her pursuits - clinical work, research, teaching, editorial work, and as a committee member of many international bodies concerned with the health and welfare of the aged. All who met her were impressed with her tremendous enthusiasm.’

RE Irvine

[Brit.med.J., 1985,290,163,405; Lancet, 1985,1,119,233; Times, 10 Dec 1984]