Under the skin: treating the body

Under the skin: treating the body

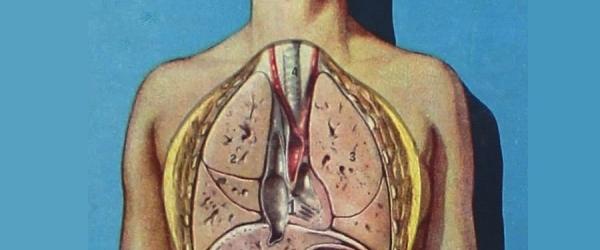

New technologies and inventions allow us to see inside living human bodies using non-invasive techniques – a contrast to earlier practices of dissecting dead bodies.

Since the 19th century, ancient medical techniques for understanding the inner workings of the body have been graphed and traced in newly accurate ways. In the 20th and 21st centuries, developments in physics and computing have made X-ray, ultrasound, CT and MRI powerful and familiar tools, translating the three-dimensional inner workings of the body onto the screen.

These technologies have changed how we think about our own bodies, enabling us for the first time to view what lies beneath our own skin. They also raise new questions about the appropriate use of images of the living patient in diagnosis and treatment.

Stethoscope. Wood, 1825.

Stethoscope. Wood, 1825.

The stethoscope was invented by the French physician René Laennec in 1816, as a tool to hear the sounds of the heart and chest more accurately.

The first English translation of Laennec’s book on the use of the stethoscope claimed that Laennec had ‘placed a window in the breast through which we can see the precise state of things within’.

The earliest models were plain cylindrical tubes. Flared ends and the binaural (two-eared) design developed during the 19th century.

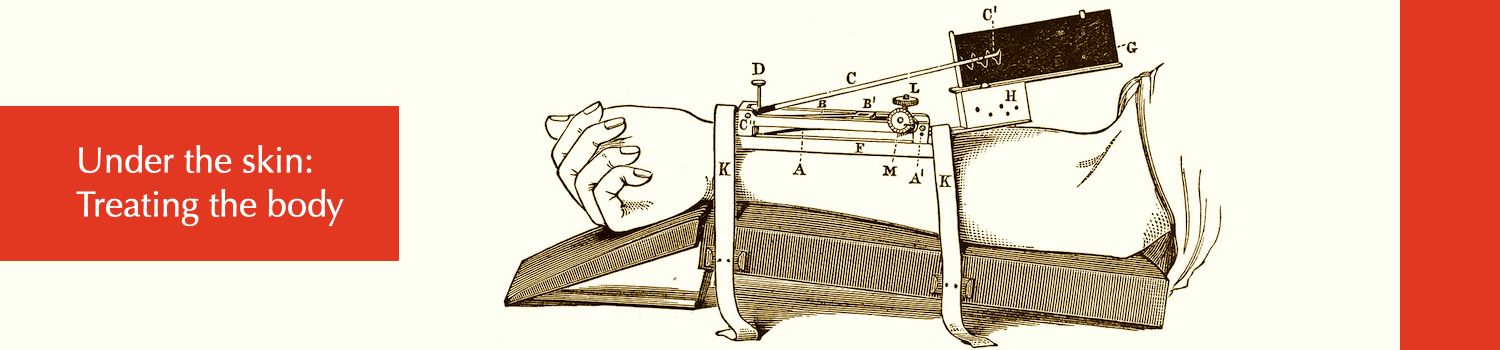

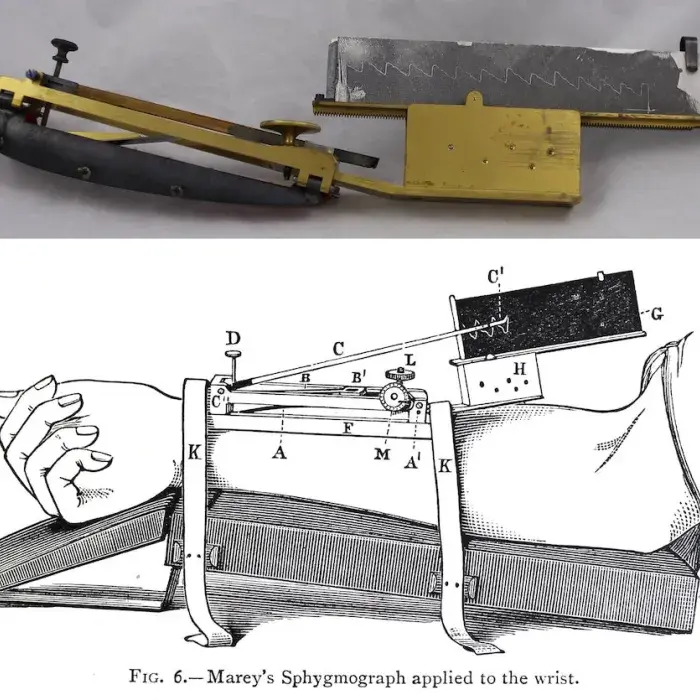

Sphygmograph made by Charles Verdin. Paris, c1870.

Sphygmograph made by Charles Verdin. Paris, c1870. Accepted from Jean Symons under the Cultural Gifts Scheme by HM Government and allocated to the RCP, 2018

Marey’s sphygmograph applied to the wrist, in Student's guide to the examination of the pulse. Sir Byrom Bramwell, published Edinburgh, 1883.

Feeling a patient’s pulse has been a diagnostic tool for thousands of years. With the mid-19th century invention of the sphygmograph – a device for recording the pulse through the skin – the beating of the heart became visible.

The tracings from the sphygmograph show the movement made by an artery or vein under the patient’s skin, creating an illustration of the movement of the living heart on a page.

View catalogue record for the sphygmograph

View catalogue record for Student's guide to the examination of the pulse

Movement of joints by cineradiography

X-ray images are a very familiar diagnostic tool today. Their 1895 discovery by Wilhelm Röntgen was revolutionary, and almost immediately their potential was understood for medicine. For the first time, doctors could see inside a living body without having to cut into it first.

X-ray images are not straightforward representations of internal structures in the body. They show the shadows of dense materials and need careful interpretation. William Osler's popular medical textbook The Principles and Practice of Medicine (1918) warned that X-rays alone are not enough to diagnose disease:

In the majority of cases [of lung disease] the X-rays tell no more than a careful clinical examination ... radiographers need the salutory lessons of the dead house to correct their visionary interpretations of shadows.

This film uses moving X-ray images, known as cineradiography, and standard film, to show how the bones move relative to each other, and to compare the internal and external appearance of the body.

Abridged from a film by the Nuffield Institute for Medical Research and Nuffield Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, 1945, and held by the Wellcome Library, London.

Every body is an archive

Every body is an archive. Liz Orton and Lori E Allen, 2019.

This film explores the ways in which new technologies are changing the relationship between the inside and outside of the body. It considers the implications of the ‘computerisation’ of the body, asking for all that computers can ‘see’, what do they know and how can they care?

Documentary and archive footage are combined with visualisations of 3D data from both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, overlaid with a text written and performed by Liz Orton.

The film is based on Orton’s experience of looking at medical images of her mother’s body after her mother’s death.

Barbra Bannister recalls how early ultrasound saved a patient with a brain tumour.

Barbara Bannister (b.1948) is a fellow of the RCP who specialised in infectious and tropical diseases. She studied medicine at the Royal Free Hospital in London.

'Up until I was a registrar there was absolutely no imaging except for X-Ray. There was a little bit of isotope imaging to look for brain tumours, but it was X-Ray, if you wanted to do a tomogram you could do an X-Ray tomogram which was mechanically managed like a, a gigantic record changer under the patient, and it was very exciting, but the pictures weren’t very revealing. And when I was a registrar I was working at Whipps Cross Hospital and greyscale ultrasound was just being invented. And excitingly we used it to, it would be totally inappropriate now, but it helped then to look at a person who was developing long tract motor signs in their, in their neurology, and the radiologist said, "I’ve got this new ultrasound machine and I’m going to have a go with it," and it revealed a tumour and it was a meningioma, and the patient was rescued. And we thought it was wonderful, and the radiologist floated around on another planet for several days after that.'

View the catalogue record for Barbara Bannister's interview

Explore more oral history recordings about anatomy and imaging

Michael de Swiet speaks about the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy.

Michael de Swiet (b.1941) is a retired obstetrician. He studied medicine in Cambridge and London, and worked in San Francisco as well as in the UK.

'But I guess it’s the advances in imaging that would have been most important to me both as a physician and in my relationship with the obstetricians because there is as much concern about the use of X-rays in pregnancy as there is about the use of prednisone in pregnancy. You know, people would throw up their hands in horror at the thought of having a chest x-ray in pregnancy not knowing that if they flew to the United States they’d get just as much radiation to their foetus from the altitude and the thin air as they would have done from a chest X-ray. So ultrasound is, is hugely important in obstetric practice as of course it is in general medical practice. And when I first started there were so called A scans and, and people could manage to get some information about the, the foetus just from bouncing sound waves and looking at the lines that these produced on the screen. But, you know, now the, the resolution and, and speed of capture of results is, is wonderful. So there’s a huge, huge amount of information about foetal wellbeing that ultrasound has, has brought.'

View the catalogue record for Michael de Swiet's interview

Explore more oral history recordings about anatomy and imaging

Untitled: black MRI. Rebecca Harris, fabric and machine embroidery, 2013.

Untitled: black MRI. Rebecca Harris, fabric and machine embroidery, 2013.

This work shows the ‘landscape’ and contours of a female body described as overweight, as represented in the layers of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Overweight and obese bodies are often criticised and disregarded in science and medicine, and this body also suffers a loss of identity by being rendered anonymously as reconstituted scan data.

The fabric sheet on which the image has been embroidered is like a shroud or curtain: a covering that medical imaging helps – partly – to lift.

LEFT: Stitching Science with Rebecca Harris

Rebecca Harris discusses her work on display in 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity', with a focus on her use of textiles to unveil what lies beneath our surface.

Through tracing our relationship with cloth, Rebecca talks about how she adopts the material to explore not only how this everyday fabric conceals our bodies, but how, through embroidery and manipulation of the material, the works can reveal physical and psychological states.

Recording of the Digital Museum Late held on 1 October 2020.

Deep seated anxiety by Rebecca Harris and The Bud by Sofie Layton

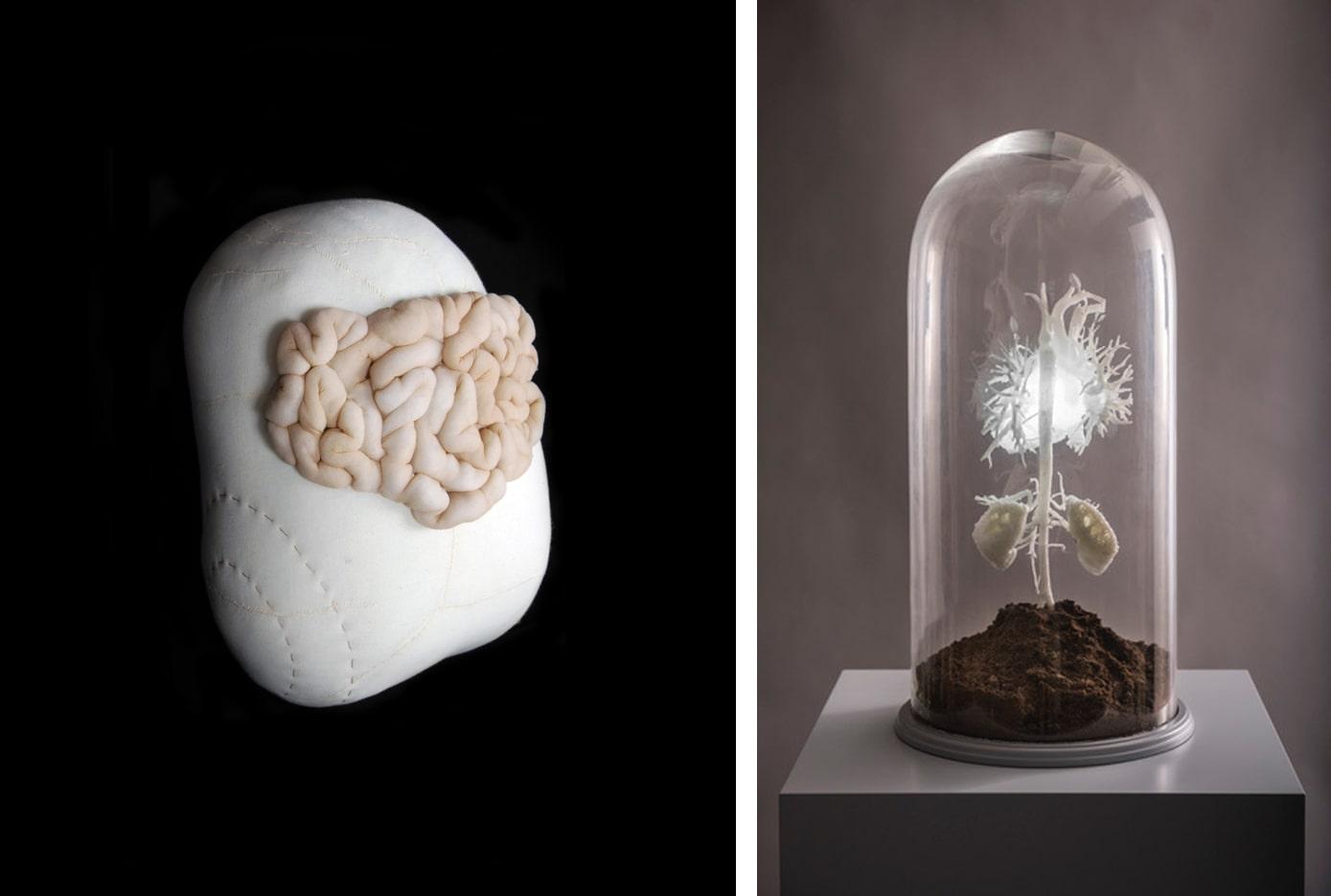

LEFT: Deep seated anxiety. Rebecca Harris, stuffing, calico, thread and tights, 2012.

Internal organs are bursting through the skin in this unsettling textile piece. It expresses the profound unease some patients experience when they see images of their hidden anatomy in medical scans.

Non-invasive medical imaging provides unprecedented diagnostic information, but it can also feel extremely unnatural to witness parts of the body that are normally inaccessible.

RIGHT: The Bud. Sofie Layton, 3D printed model of heart, vasculature and kidneys in 1:1 replica, 2018.

We often feel or hear the movements of our heart. Modern magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques mean that patients can now see their own hearts, and even hold personalised models of their own organs.

This artwork was developed in collaboration with bioengineer Giovanni Biglino, as part of The Heart of the Matter, a national touring exhibition exploring the medical and metaphorical heart. The project began as a residency at Great Ormond Street Hospital. Layton worked alongside patients, families and medical staff to explore the meanings of the heart, and ways of understanding medical images of the body.

Funded by Wellcome Trust and Arts Council England.

LEFT: Narratives of the heart

Artist Sofie Layton discusses her art-making practice and the challenges and benefits of transdisciplinary work with collaborators Dr Jo Wray and Dr Giovanni Biglino.

Sofie began this collaboration during a her residency at Great Ormond Street Hospital, and went on to be the artistic lead on 'The Heart of the Matter', a national project exploring the medical, experiential and poetic dimensions of the heart (2016-2018).

Recording of the Digital Museum Late held on 3 December 2020.

Part of the exhibition 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity'. Explore further: