Related pages

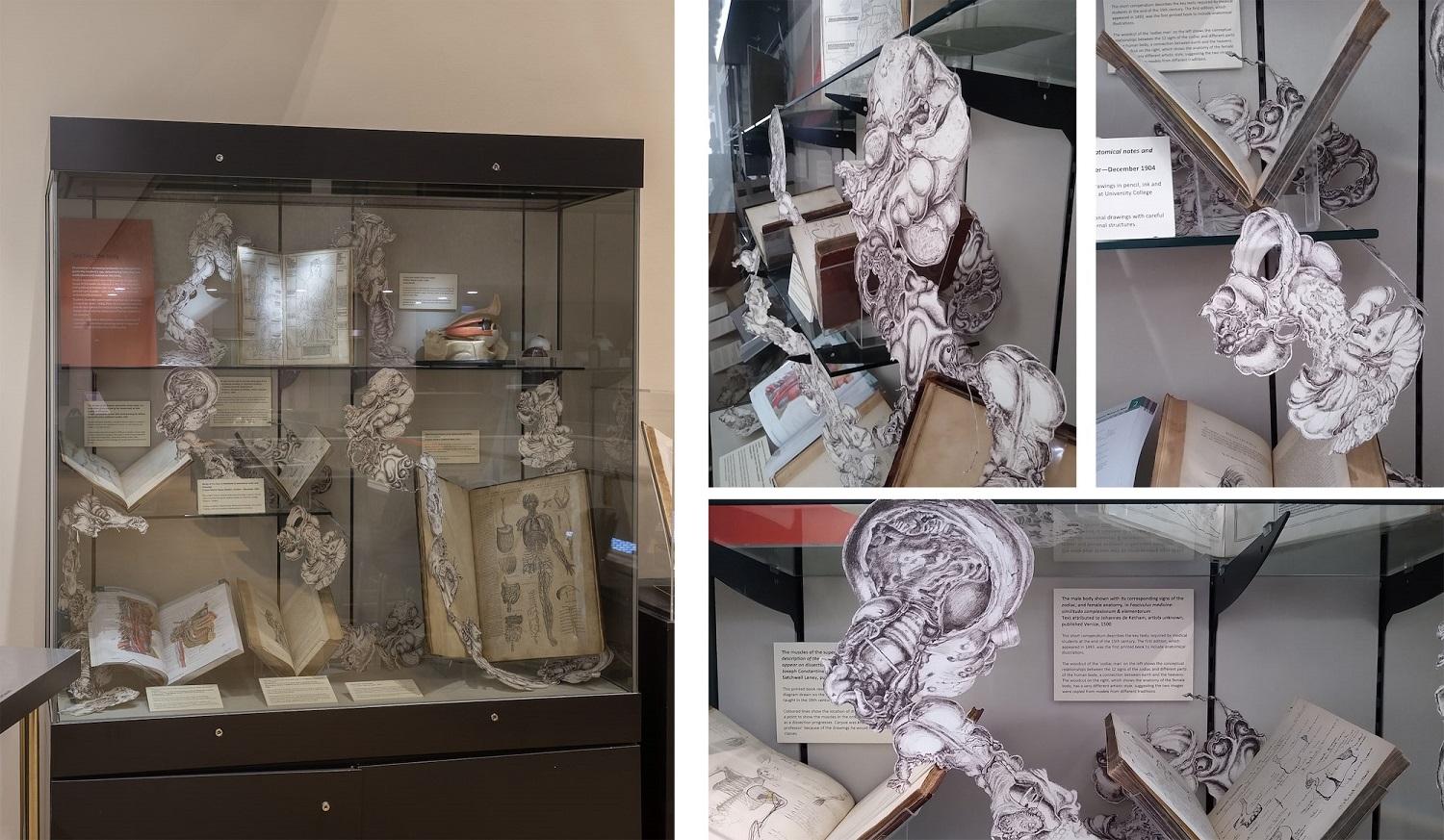

‘Curious anatomys’: an extraordinary story of dissection and discovery

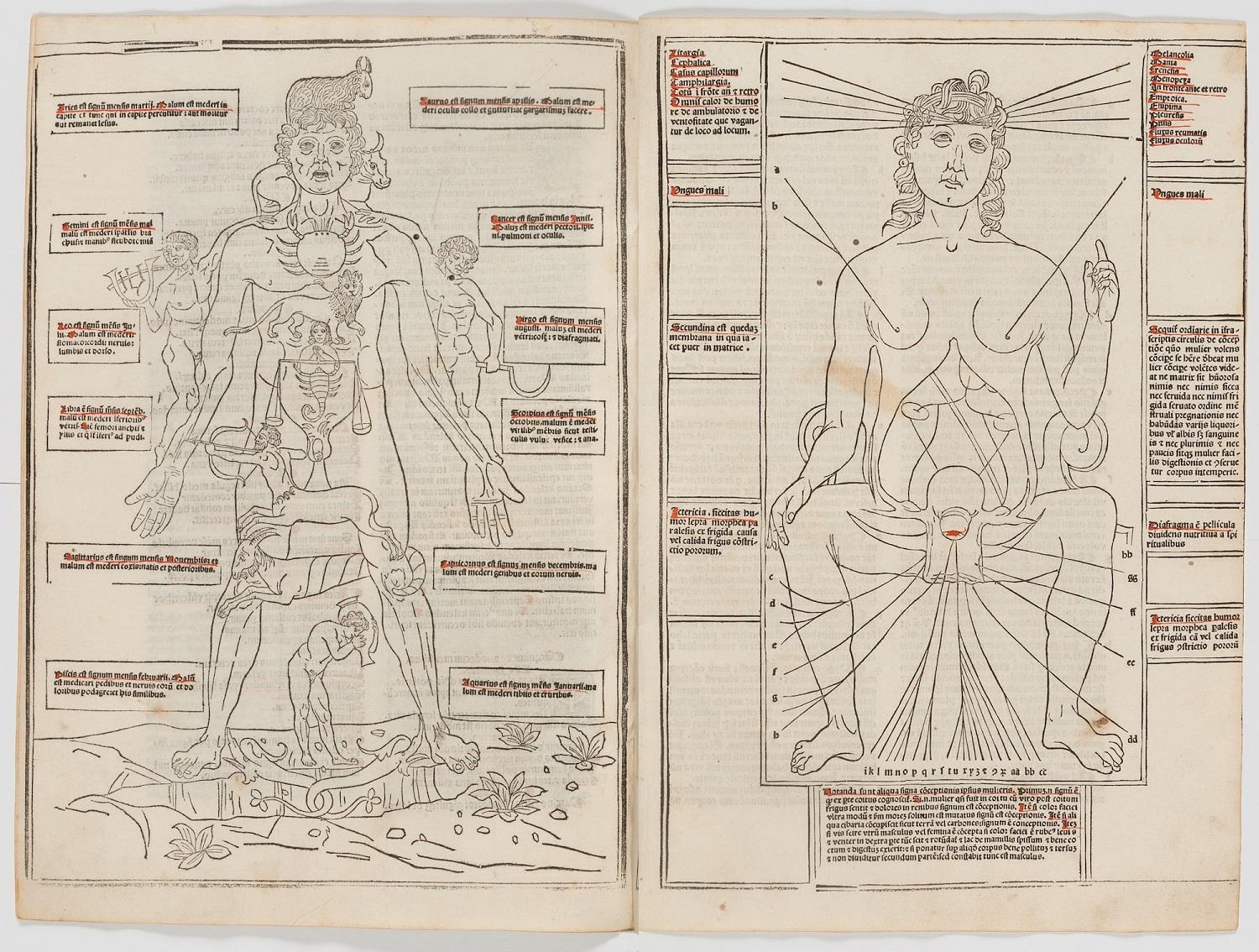

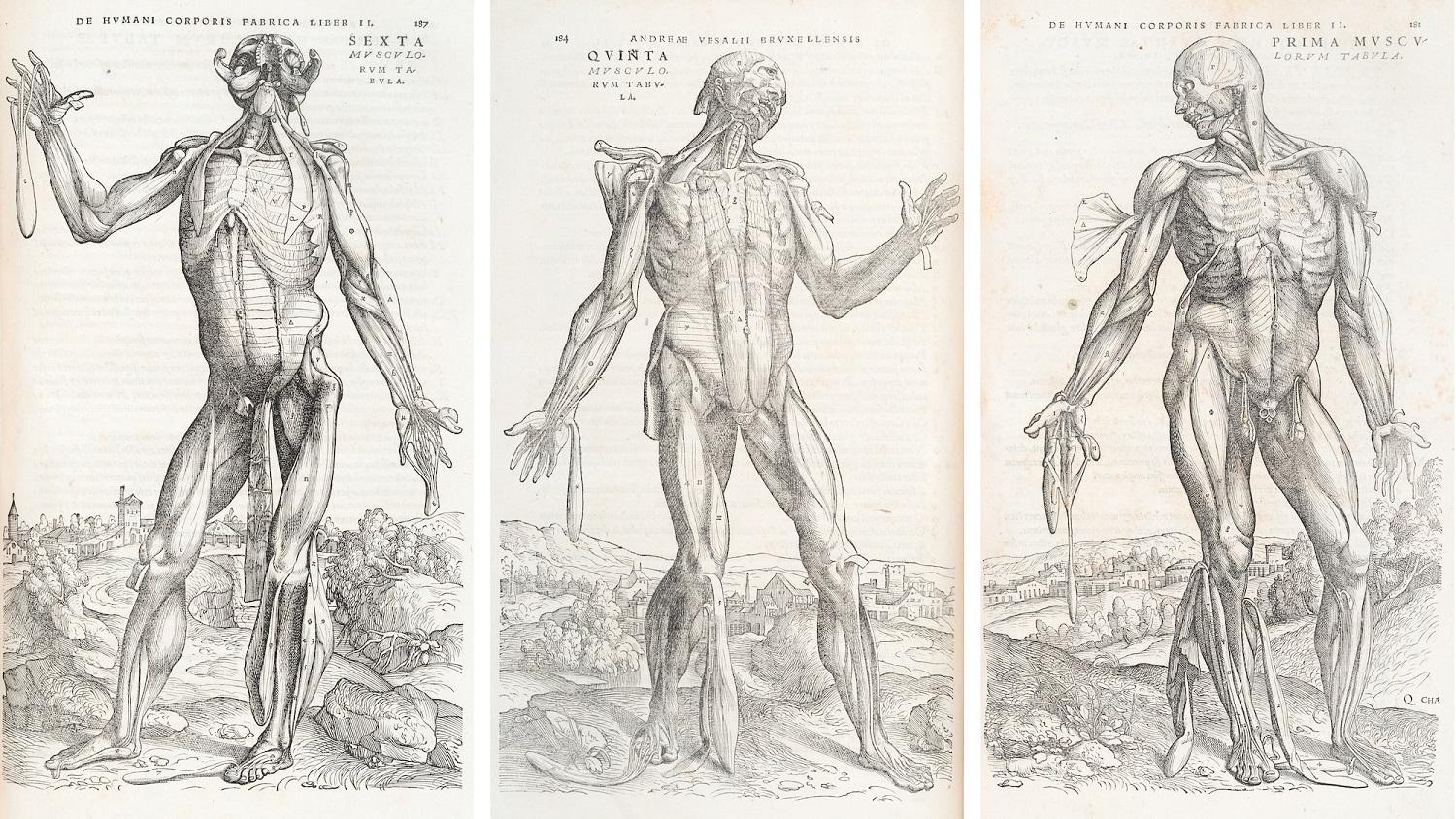

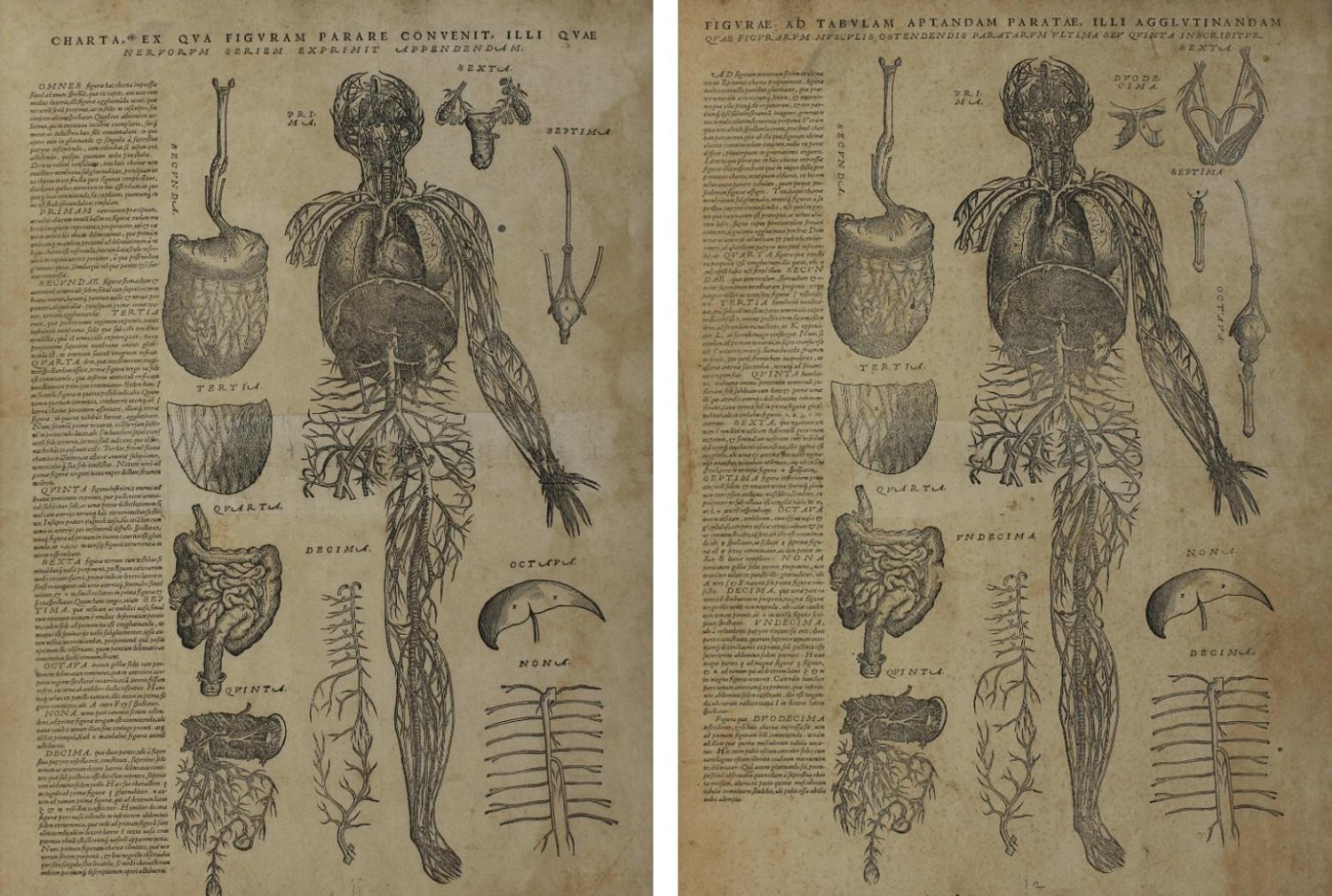

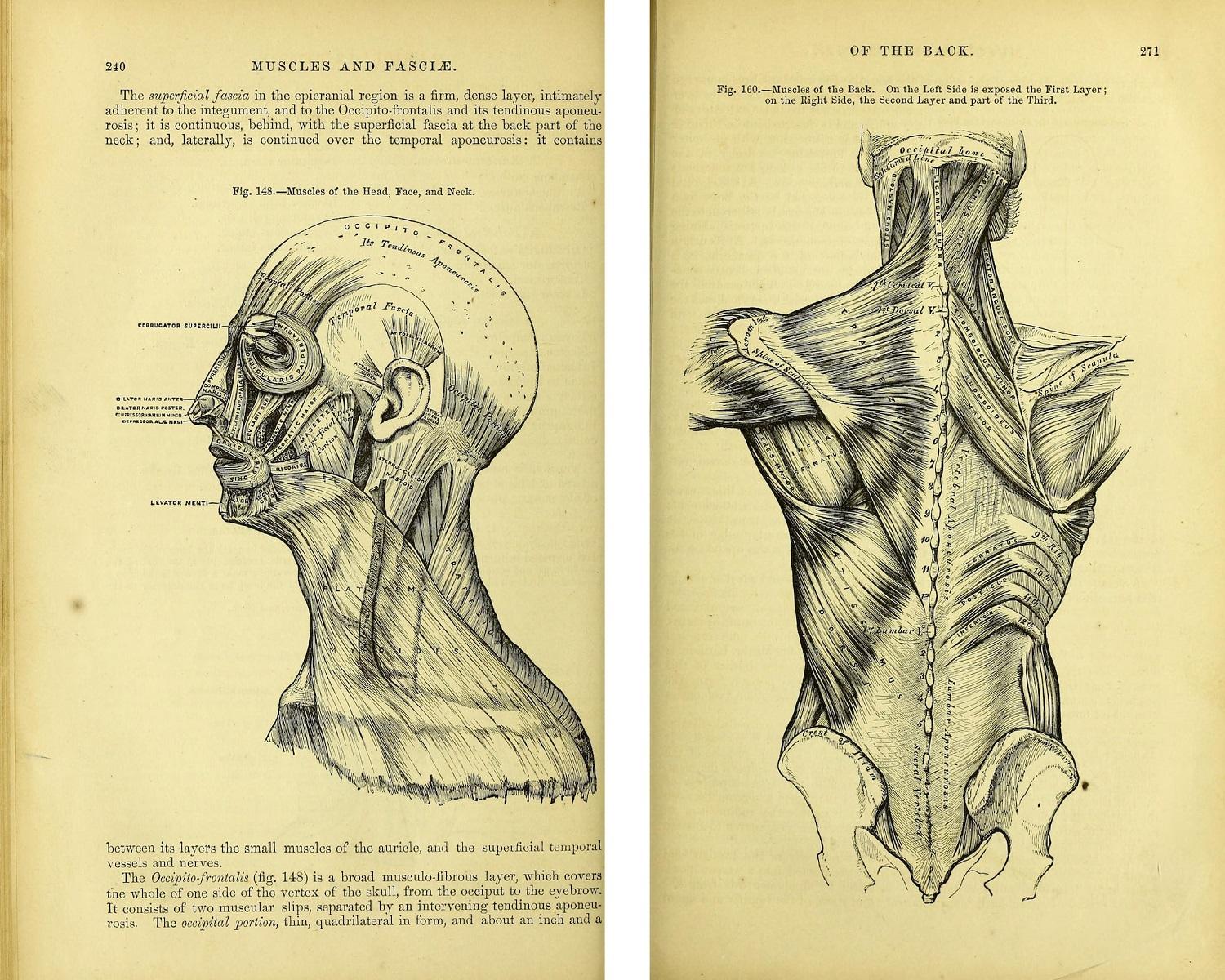

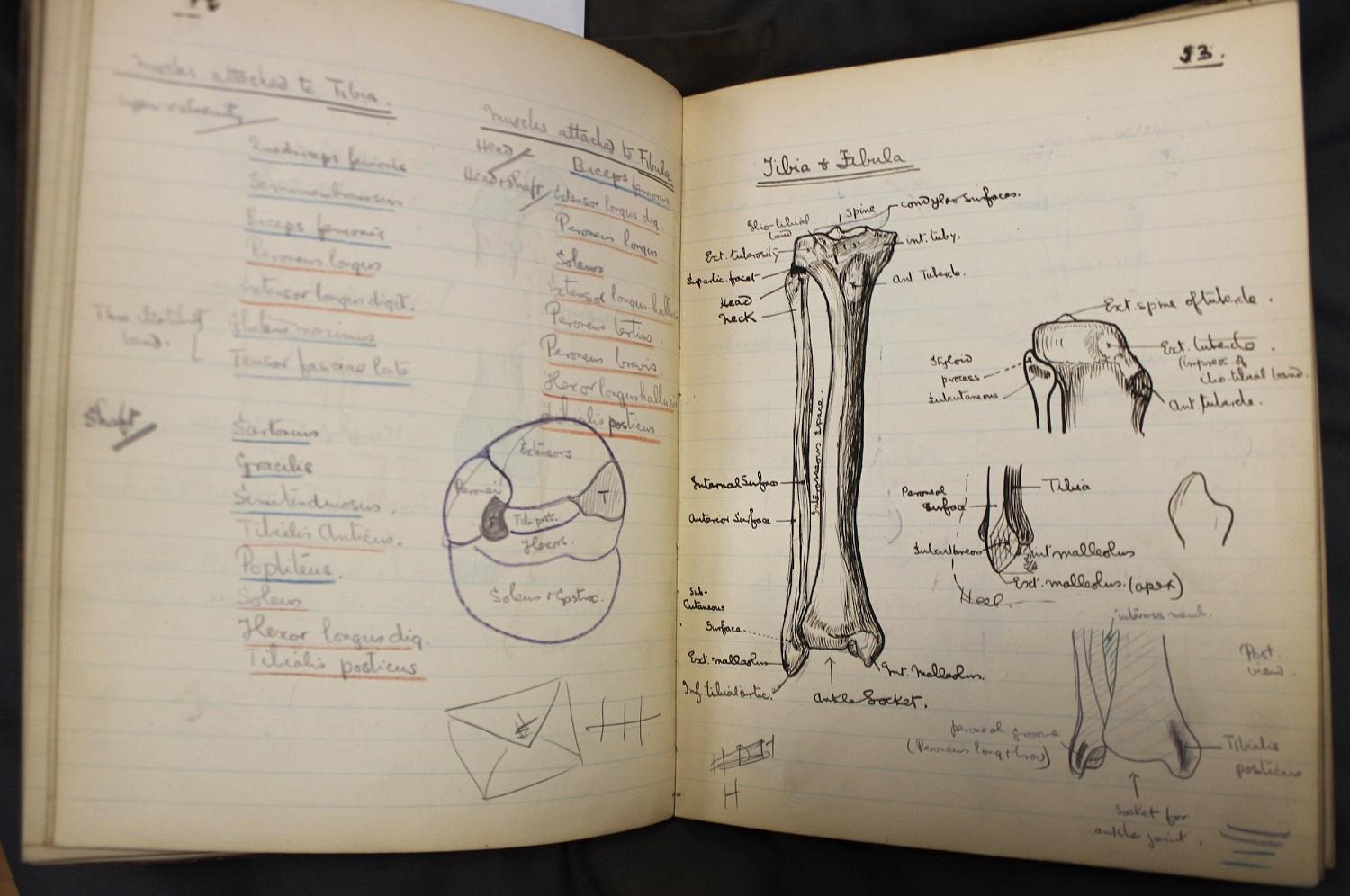

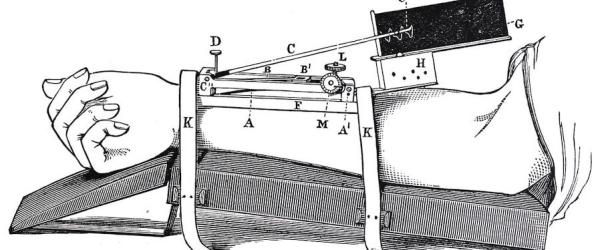

Human remains, graphic models and detailed illustrations; the Royal College of Physicians’ (RCP) latest exhibition showcases some of the 494 year old organisation’s rarest and most fascinating exhibits.

Curious anatomy's: an extraordinary story of dissection and discovery

The Royal College of Physicians holds a rare set of six anatomical tables which are amongst the oldest surviving human tissue preparations in the world.

Royal College of Physicians, 11 St Andrews Place, Regents Park, NW1 4LE