Under the skin: opening the body

Under the skin: opening the body

Much of our knowledge of the organs, tissues and systems inside us comes from the dissection of dead human bodies.

Anatomical illustrations often bring us right into the dissecting room – where artists and anatomists worked together to replicate the inside of the body as accurately as possible.

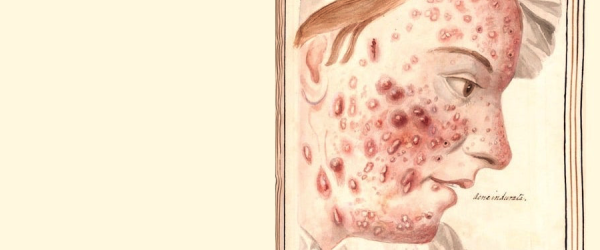

In these images, two-dimensional printing and engraving techniques show different textures of human tissue. Colour is added to bring realism, or to identify different systems. Occasionally dissection tools and methods are included, such as pins, hooks, folded-back skin and scalpels. These are both technical information for anatomists replicating the dissections, and a reminder to other viewers of the often brutal techniques necessary for medical research.

Human bodies have been dissected in Europe from around the middle ages, leading to great advancements in our understanding of human anatomy and medicine. However, for many centuries the anatomist’s dissection room was greatly feared, and in some cultures the dissection of human bodies is prohibited. These images remain very difficult to look at.

Surgical tools and dissection kit

Dissection set. Wood and metal, late 19th or early 20th century.

This kit contains equipment for dissecting bodies: a pair of tweezers, six scalpels, a probe, and a set of triple-chained hooks for holding back flesh and organs during the work. A pair of scissors would also have been included but are now lost.

This set belonged to the physician Sir Wilmot Parker Herringham, one of the first doctors to investigate the effects of poison gas in the First World War.

View the catalogue record for the dissection set

Surgical tools. Tamsin van Essen, porcelain, 2016.

Tamsin van Essen recreated prehistoric and modern surgical implements in her series ‘Surgical tools’. The simple lines of the undecorated porcelain focus our attention on their shape, and on the brutal actions the tools are designed to perform.

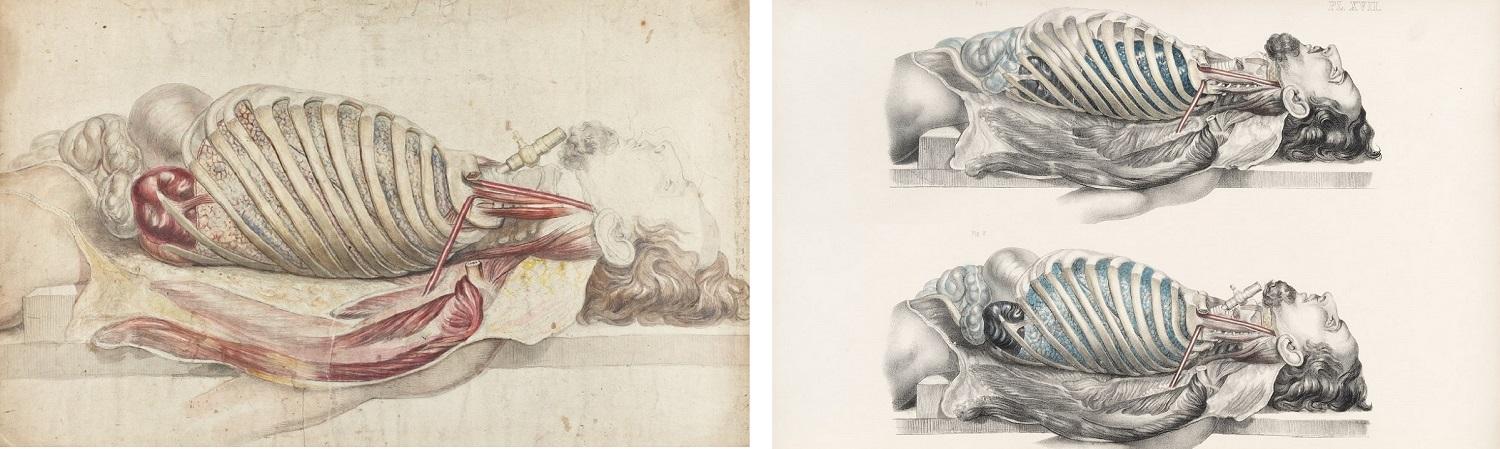

Anatomy of the male torso

Anatomy of the male torso. Francis Sibson, 1860s.

This is one of the original drawings for Francis Sibson’s book Medical anatomy, or, Illustrations of the relative position and movements of the internal organs. A dissected body on the dissecting table is depicted in pencil and watercolour. You can see through the ribs to the lungs and other internal organs.

Sibson has included facial features and hair, creating a vivid image of an autopsy, and a portrait of a real body. The original drawing is more individualised and personal than the simplified version that appeared in the published book (shown below).

View the catalogue record for Sibson's anatomical drawings

Anatomy of the male torso, in Medical anatomy, or, Illustrations of the relative position and movements of the internal organs. Francis Sibson, published London, 1869.

Sibson has shown the same body twice: with the lungs in their natural position and with the lungs inflated through a tube inserted into the neck.

Together, these drawings illustrate the constant movement of air in and out of the chest cavity during life. They show how the position of the lungs – and all the organs beneath including the spleen, kidney and intestines – change as we breathe.

Anthony Seaton describes attending post-mortems as a student

Anthony Seaton (b.1938) studied medicine at the University of Cambridge and in hospitals in Liverpool in the 1960s. He worked as a chest physician and became a leading expert in occupational medicine.

'What I started to realise, was the power of physical examination and also very quickly in, in those three years at Liverpool I learnt the value of post-mortem examinations and I was an assiduous attender at post-mortems. You might laugh at this but they were held on lunch time [laughing] and the Liverpool Royal Infirmary students were invited, they didn’t have to go but they were invited to go to the post-mortems at lunch time and you could see two or three done and then you’d see the slicing the liver up and then you go to the canteen and they’d have liver on the menu [laughing]. But I, I realised how important a post-mortem was in revealing what had been missed in life and I got very interested in physical examination and how, how much you could deduce from a physical examination about what was going on inside somebody, much more than the average lay person would think.'

View the catalogue record for the Anthony Seaton's interview

Explore more oral history recordings about anatomy and imaging

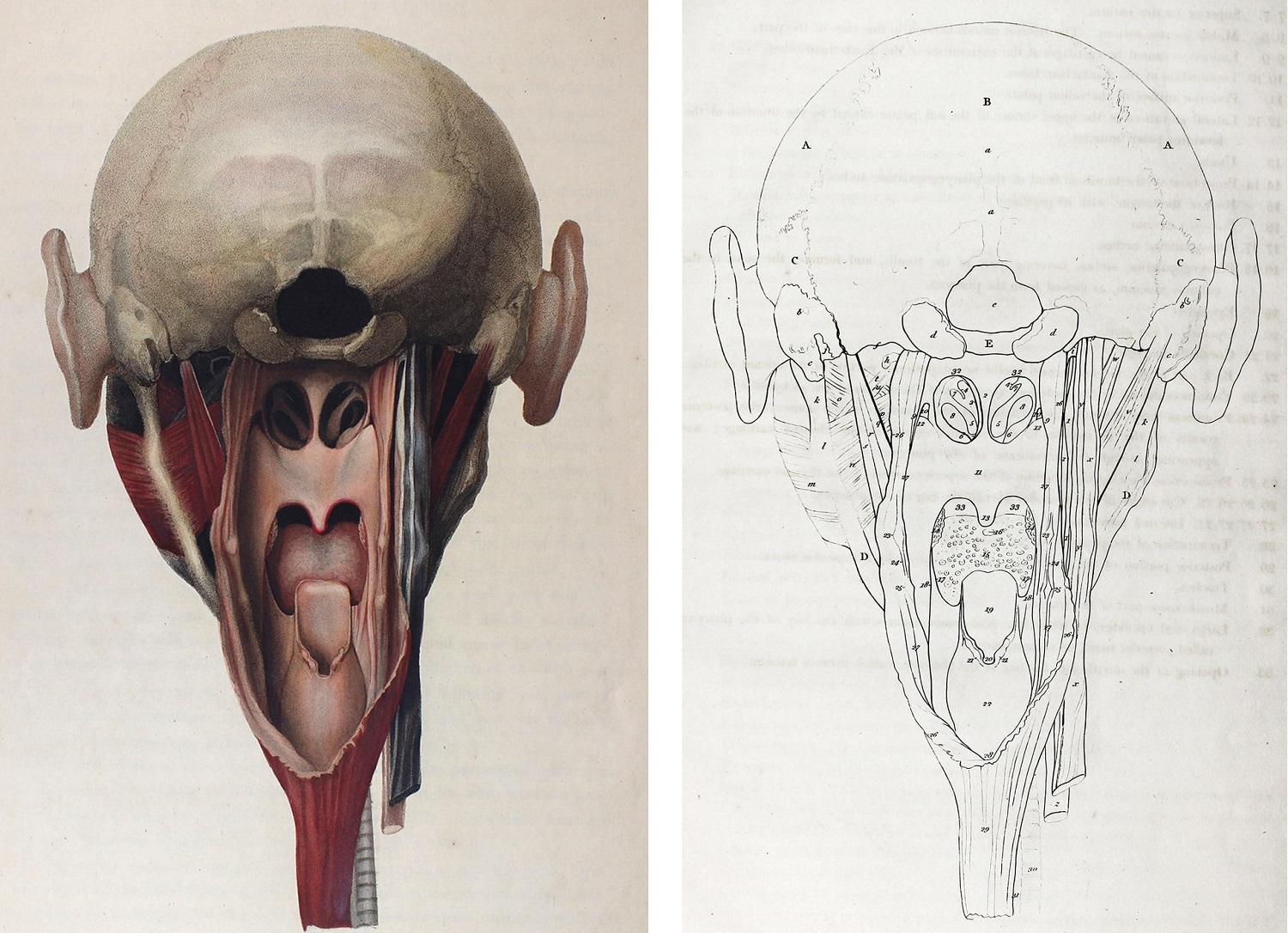

Anatomy of the head

Anatomy of the head, in Anatomico-chirurgical views of the nose, mouth, larynx, & fauces. Dissection and text by John James Watt, drawing by T Baxter, stipple engraving by J Hopwood, published London, 1809.

We are given an unusual view of the internal anatomy of the head in this engraving, looking forwards through the cavity of the mouth and nasal passages. The hand-colouring creates a strong sense of depth, as if we are penetrating deeply into the skull. The smooth surfaces make this appear like a drawing of a model, rather than a body.

The illustrations in this book are each accompanied with a line drawing, used to label the individual parts.

View the catalogue record for Anatomico-chirurgical views of the nose, mouth, larynx, & fauces

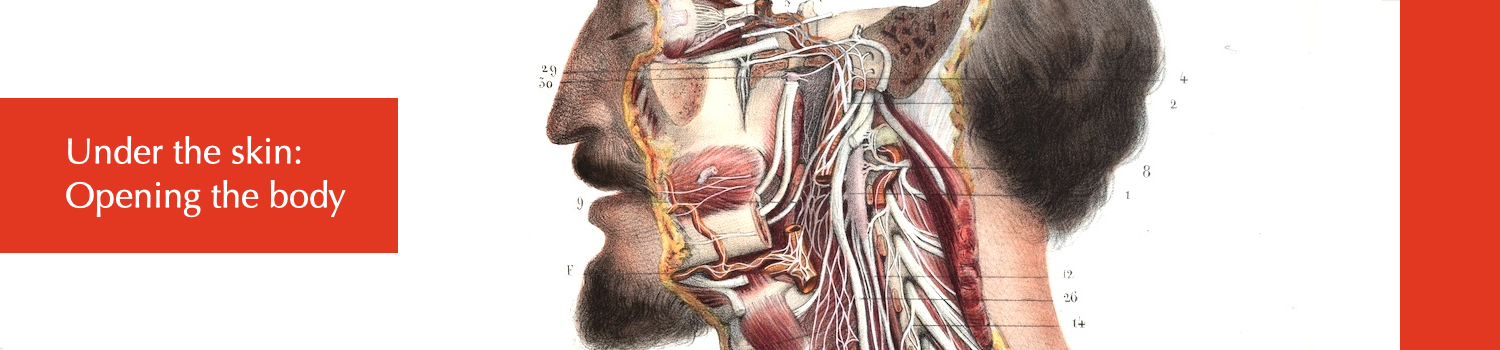

The nervous system of the head, neck and torso

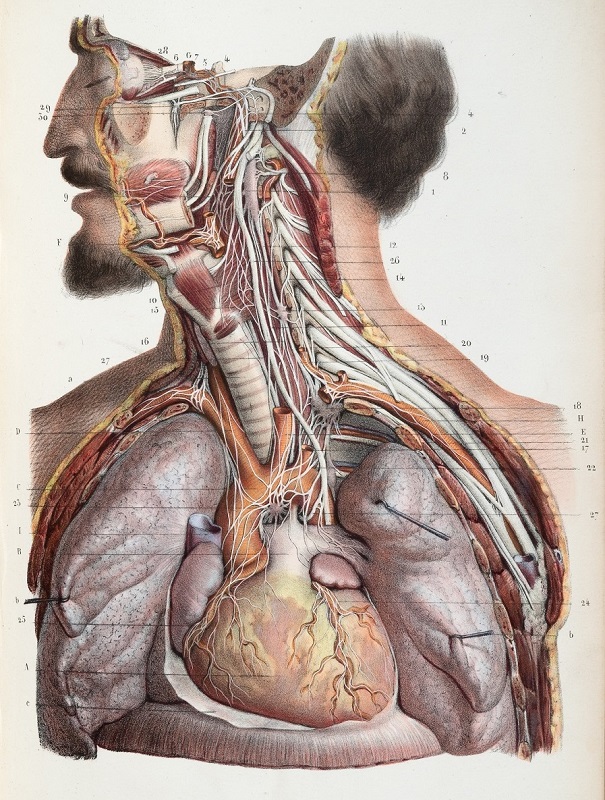

The nervous system of the head, neck and torso, in Nevrologie. Dissection by Ludovic Hirschfeld, drawing by Jean Baptiste François Léveillé, lithograph by Lemercier, published Paris, 1853.

The realism of this hand-coloured printed lithograph is startling.

Lithographs are made by printing from a drawing made in greasy crayon on a stone plate, giving a distinctive textured effect. Here, the grey tone of the print has been overlaid with colour by hand, creating a vivid three-dimensional effect.

Clearly visible are the dissection hooks, used here to hold back the tissue of the lungs to reveal the heart beneath. Including the instruments of dissection in an anatomical image is one way to demonstrate its authenticity, by showing that the author and artist have seen dissections themselves.

Part of the exhibition 'Under the skin: anatomy, art and identity'. Explore further: