Under the skin: knowing the body

Under the skin: knowing the body

Though images of anatomical dissections were generally produced for and used by teachers and students, they were also viewed by non-specialists including the general public.

Some anatomical illustrations were created specifically for an audience with limited medical knowledge. Artists and publishers faced a new challenge: how do you simplify human anatomy for a non-medical audience?

The resulting illustrations use bold and arresting images to capture and hold attention. Moving parts make the books fun to use and help to represent different layers without the need for lengthy explanations or multiple illustrations.

Anatomical volvelle

Volvelle showing female anatomy, in Bodyscope. Ralph H Segal, published New York, 1948.

Large rotating card discs – called volvelles – are used in this book to reveal the different functions of the body, including the circulatory, respiratory, excretory and reproductive systems.

Over four pages the book gives a general overview of anatomy and the history of medicine, as a fun reference guide for all the family. The bodies shown are stereotypical young, white, blonde ‘ideals’ of American good health.

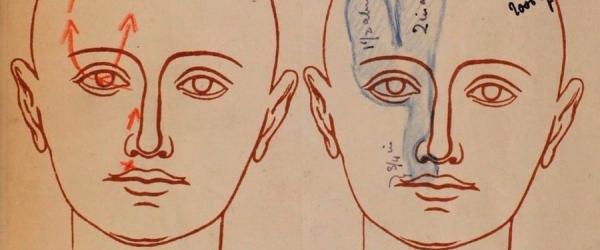

Fold-out illustration showing the anatomy of the head

Fold-out illustration showing the anatomy of the head, in La nuova medicina naturale. Friedrich Eduard Bilz, published Leipzig, c.1895.

These lift-the-flap pictures have an almost cartoon-like quality, with bright colours and simple lines. They are from a very popular guide to ‘natural’ medicine that relies on diet, water, air and light and avoids professional medical care.

Printed anatomical lift-the-flap books were first developed in the 16th century, but were most prevalent in the late 19th century, when colour printing technology became cheaper and more accurate.

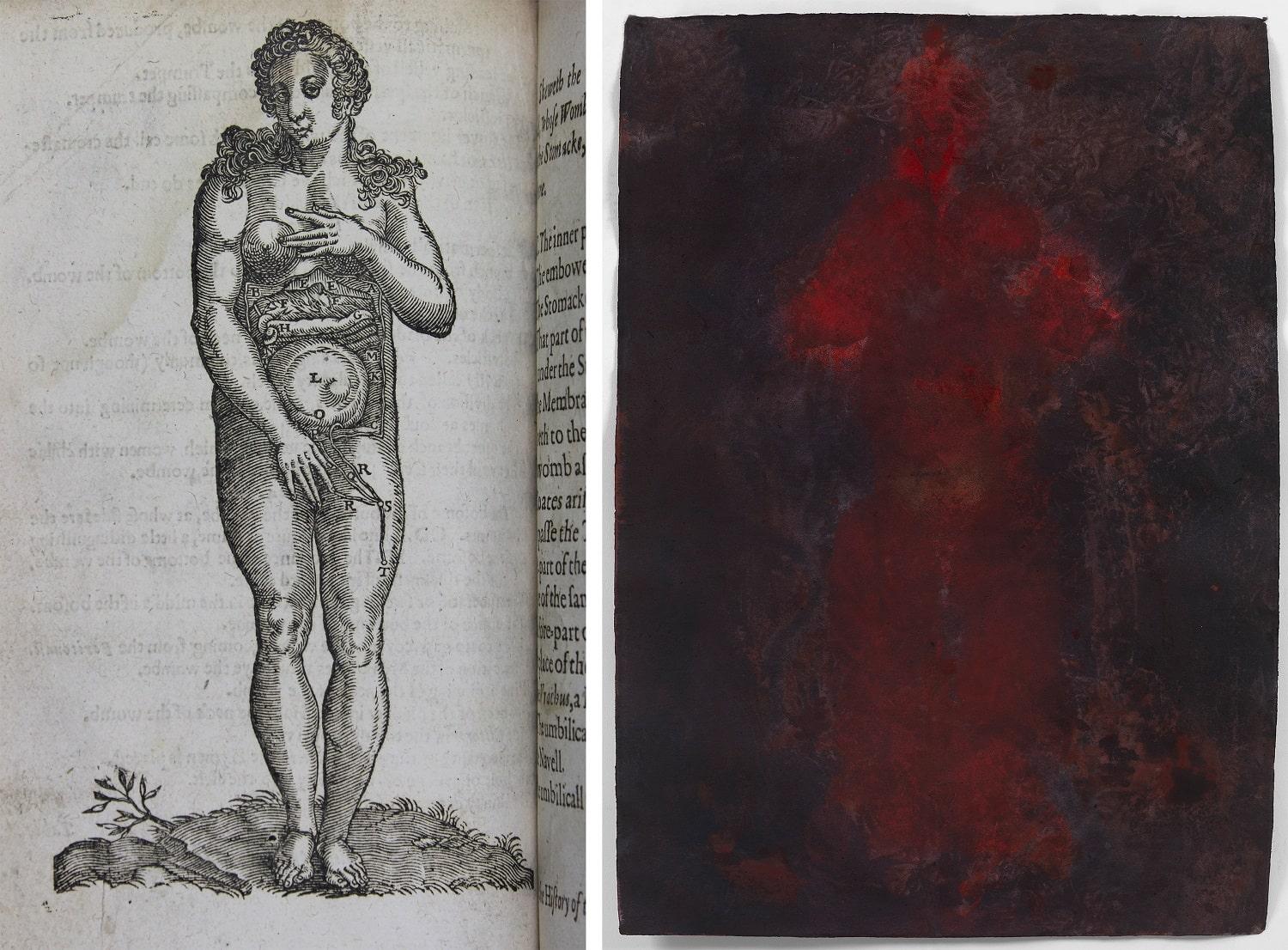

Representing the female body

LEFT: The abdomen and womb in late pregnancy, in Sōmatographia anthrōpinē. Or, A description of the body of man. Text by Helkiah Crooke, abridged by Alexander Read, illustrations after various models, published London, 1634.

The Royal College of Physicians tried to ban the first edition of this book, called Mikrokosmogaphia, because the language it used to describe anatomy – English – was considered inappropriate. Latin was the preferred language of learned scholars, and was not understood by most people in the country.

The physicians were particularly concerned that these woodcut illustrations of the reproductive system were indecent and could corrupt public morals, and recommended that they be removed from all copies.

View the catalogue record for Sōmatographia anthrōpinē

RIGHT: Fernande. Adelaide Damoah, ink on hand made cotton rag paper, 2018.

Adelaide Damoah is a painter and performance artist who uses her body as a printing tool to create her works.

By using this technique, Damoah takes direct control of how she – as a black woman – is depicted. She challenges the sexual and racial stereotypes of, in her own words, ‘passive female bodies, ripe for objectification and sexualisation by the male gaze’, which are pervasive in artistic and medical representations.

Damoah’s life-size body prints are individual and personal images. They are visually similar to the anatomical tables displayed upstairs. These tables preserve the bodies of people who lived and died 350 years ago. However, any direct personal connection to these individuals has been lost because their identities were not recorded when the tables were made.

‘Fernande’ is part of the series ‘Muse, Model or Mistress?, inspired by the monologues for the muses of Picasso written by Brian McAvera and performed at Gallery Different in September 2018.

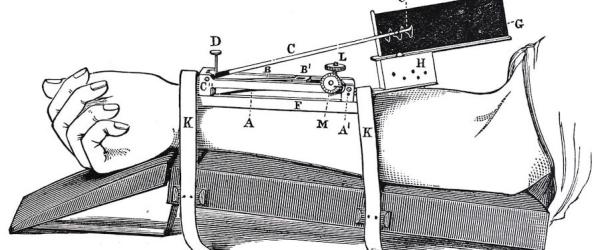

LEFT: Anatomy of the female abdomen and reproductive organs, in Anatomie iconoclastique. Gustave Joseph Witkowski, published Paris, 1874 .

The garish colouring and explicit subject matter of this multi-layered illustration is a stark contrast to what we might think of as ‘scientific’ illustration.

The many layers of flaps provide a very direct, three-dimensional representation of the body, suitable for teaching a non-specialist audience. However, the level of detail and choice of subject suggests it may have been intended for a medical audience.